Copyright 2016 by Julia C. Tobey

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

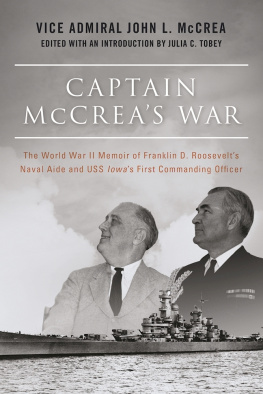

Cover design by Rain Saukas

Cover photos: Editors collection; AP Images

Print ISBN: 978-1-5107-1323-9

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-1324-6

Printed in the United States of America

Contents

Duty and War Production

Foreword

By Craig L. Symonds

To many, President Franklin D. Roosevelt was, and is, an enigma: to all appearances a relentlessly cheerful man full of good will and bonhomie despite the physical and political burdens he bore as president. Both contemporaries and historians have occasionally wondered if this demeanor was a kind of disguise or a coping mechanism, and some have sought evidence of a darker, more troubled man underneath the veneer. Only a very few ever got close enough to offer testimony about him: his wife Eleanor, his old political pal Louis Howe, Edwin Pa Watson, Harry Hopkins, and a few others.

One of them was U.S. Navy Captain John McCrea, who in the days immediately following Pearl Harbor was astonished to be plucked from a pending appointment to command a cruiser and assigned instead as the presidents naval aide. He served in that capacity throughout the critical year of 1942that is, from Pearl Harbor through Casablancaduring which time he spent part of every day with the president. He did not keep a diary, for that was forbidden by Navy regulations, but many years later, upon the urging of his family, he did write a memoir, which is published here for the first time.

McCrea saw the president every day when he was in Washington, generally once in the morning and again in the afternoon, though he often spent hours or even days in continuous proximity to him. If there was a darker persona lurking under Roosevelts veneer, McCrea never saw it. Invariably, McCrea writes, he was in good spirits and eager to talk. On many of these days, the president was still in bed when McCrea arrived, and occasionally the Navy captain, wearing his service dress blue uniform, sat on the toilet in the bathroom to read briefing papers aloud to the president while he shaved. As the president was pushed to his office in his wheelchair each morning, he greeted everyone he passed with a large smile and a cheerful hello. Cooks, gardeners, maintenance men: he knew their names and their childrens names, and often inquired about their health or their interests. As McCrea noted, his zest for living was enormous.

McCrea became FDRs go-to man for all sorts of errands, from tracking down errant visitors to providing war stories for the presidents Fireside Chats. He set up FDRs Map Room in the basement of the White House, and he supervised the modifications to the mountain cabin that became Roosevelts retreat, initially called Shangri-La and subsequently renamed Camp David. He even attended church services with the president and at least once had to come up with a couple of dollars for the collection plate when FDR forgot to bring his wallet.

Nor was theirs a relationship confined to the White House. He accompanied the president to Hyde Park and got a hair-raising high-speed tour in FDRs old Ford with its special hand-operated controls. McCrea also supervised the secret trip from Washington to Casablanca for the conference with Churchill. As McCrea writes, I had the honor and pleasure of coming to know him on a personal basis.

The topics of their conversations ranged widely. There was a lot about the Navy, of course, a subject always near to the presidents heart, but there were many other topics as well. Once at Hyde Park, the president asked McCrea if he knew much about the history of the Hudson Valley. When McCrea professed ignorance, FDR proceeded to fill him in. As McCrea puts it in the memoir, He would start off, Well, Ive been thinking about so-and-so, and he would talk.

In addition to Roosevelt, McCreas memoir also offers intimate glimpses into the lives and personalities of many of the principal players in those heady and perilous days. He had a close relationship with FDRs gatekeeper, Edwin Pa Watson, a major general in the Army reserve who acted as FDRs appointments secretary. He dealt with Navy Secretary Frank Knox, Secretary of State Cordell Hull, former Vice President John Nance Garner, and of course with the chief of naval operations, the stern and forbidding Admiral Ernest J. King.

McCreas portrait of King does little to diminish the Admirals reputation as cold, judgmental, and quick-tempered. King once counseled McCrea that, while he had the makings of a good officer, he had one outstanding weakness. When McCrea asked him what it was, King told him: you are not a son of a bitch. A good naval officer, King insisted, has to be a son of a bitch. Nevertheless, McCrea got on well with King, whom he admired for his professional efficiency, and on more than one occasion he was even able to elicit a gentle chuckle from the famously humorless Navy Chief.

But it is always FDR who shines brightest in this memoir. There was the presidents great love of the Navy (which he liked to call my navy), his suspicion of the State Department (which he considered leaky), and his bantering relationship with the press. The president could be blunt if necessary, even to Churchill, but he always managed to lighten the mood afterward with a kind word or a story, often throwing his head back and laughing aloud. Indeed, laughter seems to have been one of FDRs principal weapons, deployed frequently and deliberately to fend off enquiries as well as to lighten the mood.

During the conference at Casablanca, Roosevelt tasked McCrea to deliver an invitation for dinner to the Sultan of Morocco, and McCrea paints a vivid word portrait of his reception by the Sultan. No Hollywood director could have put on a more dazzling spectacle, he writes. At the dinner, where the sultan presented a gold dagger for the president and a gold tiara for Mrs. Roosevelt, Churchill was visibly upset that in deference to the sultan, no alcohol was served.

McCrea left his job as the presidents naval aide in January of 1943 to take command of the new-construction battleship USS Iowa . His relationship with the president was not at an end, however. Very likely at Roosevelts suggestion, King selected the Iowa to carry the president and his staff to Algeria, the first stop on the trip to the Cairo and Tehran conferences. The voyage across the Atlantic included a then-secret but subsequently notorious accident in which a U.S. Navy destroyer inadvertently fired a live torpedo at the Iowa while the president was on board.