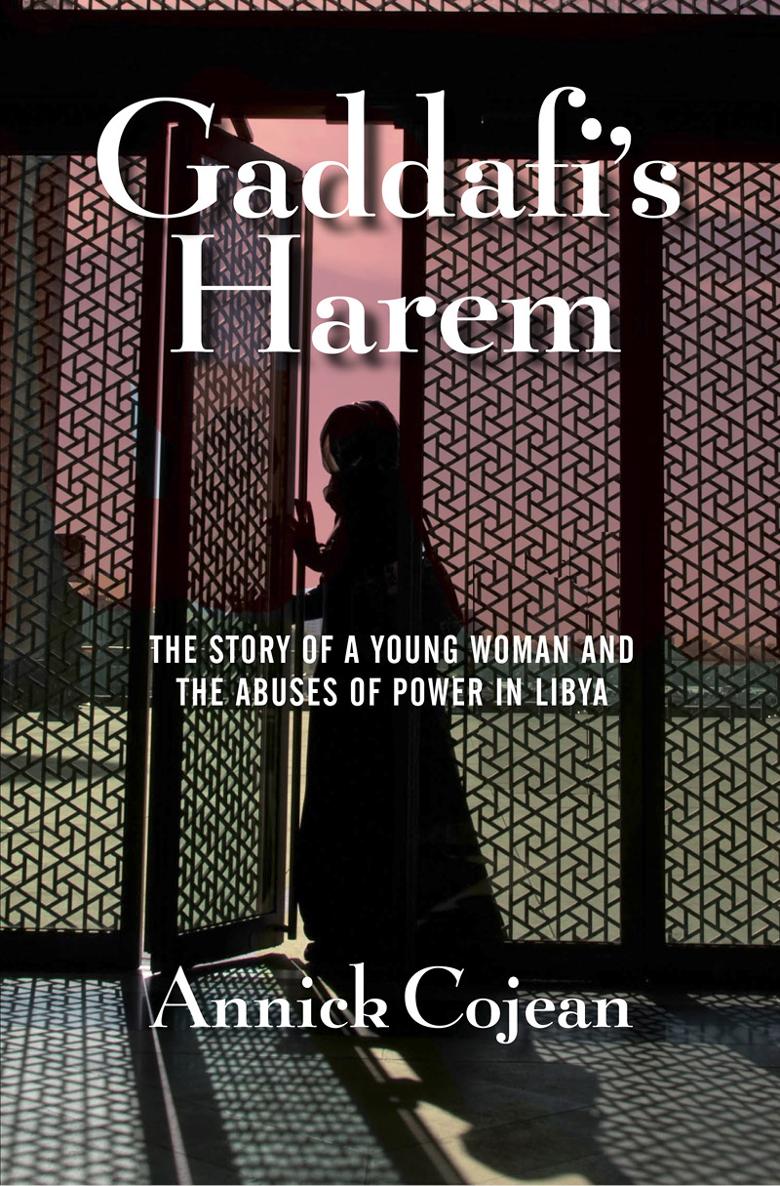

Copyright Editions Grasset & Fasquelle, 2012

Translation copyright 2013 by Marjolijn de Jager

Jacket design by Charles Rue woods;

Jacket photograph Frank van den Bergh / Getty Images

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any

form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information

storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the

publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a

review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book

or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is

prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and

do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted

materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated.

Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or

all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries

to Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 154 West 14th Street, New York, NY 10011

or .

First published in French in 2012 by Editions Grasset & Fasquelle

as Les Proies: Dans le Harem de Kadhafi

eBook ISBN-13: 978-0-8021-9402-2

Grove Press

an imprint of Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

154 West 14th Street

New York, NY 10011

Distributed by Publishers Group West

www.groveatlantic.com

We in the Jamahiriya and the great revolution affirm

our respect for women and raise their flag. We have decided to

wholly liberate the women of Libya in order to rescue them from

a world of oppression and subjugation in such a way that they will become

masters of their own destiny in a democratic setting where they will have the same

opportunities as the other members of society []

We call for a revolution to liberate the women of the Arab nation,

which will be a bomb to shake up the entire Arab region, inciting

female prisoners, whether in palaces or marketplaces, to rebel against their

jailers, their exploiters, and their oppressors. This call is certain to

cause profound echoes and repercussions in the entire

Arab nation and in the world at large. Today is not just any day,

it is the beginning of the end of the era of harems and slaves []

Muammar Gaddafi , September 1, 1981:

the anniversary of the revolution, introducing

the first women to receive diplomas from the

Military Academy for Women

Prologue

First, there is Soraya.

Soraya and her dark eyes, her sullen mouth, and her big resounding laugh. Soraya, who moves quick as lightning from laughter to tears, from exuberance to despondency, from cuddly affection to the hostility of the wounded. Soraya and her secret, her sorrow, her rebellion. Soraya and her astonishing story of a joyful little girl thrown into the claws of an ogre.

She is the reason for this book.

I met her in October 2011, on one of those jubilant and chaotic days following the capture and death of the dictator Muammar Gaddafi. I was in Tripoli for the newspaper Le Monde investigating the role of women in the revolution. It was a frenzied period and the subject fascinated me.

I was no expert on Libya. In fact, it was my first time visiting the country. I was enthralled by the incredible courage of those fighting to overthrow the tyrant who had ruled for forty-two years, but also genuinely intrigued by the complete absence of women in the films, photographs, and reports that had recently appeared. The other insurrections of the Arab Spring and the wind of hope that had blown across this region of the world had shown the strength of the Tunisian women, present everywhere in public debates, and the confidence and spirit of Egyptian women, whose courage was clear as they demonstrated on Tahrir Square in Cairo. But where were the Libyan women? What had they been doing during the revolution? Was it a revolution they had wanted, initiated, supported? Why were they hiding? Or, more likely, why were they kept from view in this country that was so little known, whose image was monopolized by their buffoon of a leader, who had made the guards of his female corpsthe famous Amazonsinto the standard-bearers of his own revolution?

Male colleagues who had followed the rebellion from Benghazi to Sirte had told me theyd never come across any women other than a few shadows draped in black veils, since the Libyan fighters had systematically refused them any access to their mothers, wives, or sisters. Perhaps youll have better luck! they said to me with a touch of irony, convinced that in this country history is never written by women, no matter what.

On the first point they were not incorrect. Being a female journalist in the most impenetrable of countries offers the wonderful advantage of having access to the entire society and not just to its men. Consequently, it took me just a few days and many encounters to understand that the role of women in the Libyan revolution had been not only important but, in fact, vital to its success. A man who was one of the rebel leaders told me that women had formed the secret weapon of the rebellion. They had encouraged, fed, hidden, transported, looked after, and equipped the fighters, as well as providing them with information. They had moved money to purchase arms, spied on Gaddafis troops on behalf of NATO, redirected tons of medications, including from the hospital run by the adopted daughter of Muammar Gaddafi (the same one heuntruthfullysaid had died after the Americans bombed his residence in 1986). These women had risked unbelievable things: arrest, torture, and rape. Rapeconsidered to be the worst of all crimes in Libyawas common practice and an authorized weapon of war. They had committed themselves body and soul to this revolution. They were fanatic, spectacular, heroic. Women had a personal account to settle with the Colonel, one of them told me.

A personal account... I didnt immediately understand the significance of this remark. Having just endured four decades of dictatorship, didnt every Libyan have a communal account to settle with the despot? The confiscation of individual rights and liberties, the bloody repression of opponents, the deterioration of the health and education systems, the disastrous state of the countrys infrastructure, the impoverishment of the population, the collapse of culture, the misappropriation of oil profits, and the isolation on the international stage... why then this personal account of women? Had the author of the Green Book not endlessly proclaimed that men and women were equal? Had he not systematically presented himself as their fierce defender, raising the legal age for marriage to twenty, condemning polygamy and the abuses of the patriarchal society, granting more rights to divorced women than existed in most other Muslim countries, and founding a Military Academy for Women open to candidates from all over the world? Nonsense, hypocrisy, travesty! a famous woman judge would later tell me. We were all his potential prey.

It was at that same time that I first met Soraya. Our paths crossed the morning of October 29. I was completing my investigation and was ready to leave Tripoli the next day to go back to Paris, via Tunisia. I was sorry to be going home. Although, admittedly, I had obtained an answer to my first question, concerning womens participation in the revolution, and was returning with a whole supply of stories and detailed accounts that illustrated their struggle, so many questions remained unanswered. The rapes perpetrated en masse by Gaddafis mercenaries and troops were an insurmountable taboo, locking authorities, families, and womens organizations inside a hostile silence. The International Criminal Court, which had launched an investigation into these rapes, was itself confronted with terrible difficulties when its lawyers tried to meet with the victims. As for the sufferings that women endured before the revolution, these were brought up only as rumors, accompanied by many deep sighs and furtive glances. Whats the use of bringing up such vile and unforgivable practices and crimes? Id often hear. Never a first-person testimony. Not even the slightest story from a victim that might implicate the so-called Guide.