SANDSTORM

SANDSTORM

LIBYA IN THE TIME OF REVOLUTION

LINDSEY HILSUM

THE PENGUIN PRESS | NEW YORK | 2012

THE PENGUIN PRESS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A. Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Ireland, 25 St. Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices:

80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First American edition

Published in 2012 by The Penguin Press,

a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

Copyright Lindsey Hilsum, 2012

All rights reserved

Grateful acknowledgment is made for permission to reprint excerpts from the following copyrighted works: Epitaph on a Tyrant and Sonnets from China from Collected Poems of W. H. Auden. Epitaph on a Tyrant, copyright 1940 and renewed 1968 by W. H. Auden. Sonnets from China, copyright 1945 by W. H. Auden, renewed 1973 by The Estate of W. H. Auden. Used by permission of Random House, Inc. and Curtis Brown, Ltd.

Mersa from Collected Poems by Keith Douglas. Used by permission of Faber and Faber Ltd.

Blood and Lead from Out of Danger by James Fenton. Reprinted by permission of Peters Fraser & Dunlop on behalf of James Fenton.

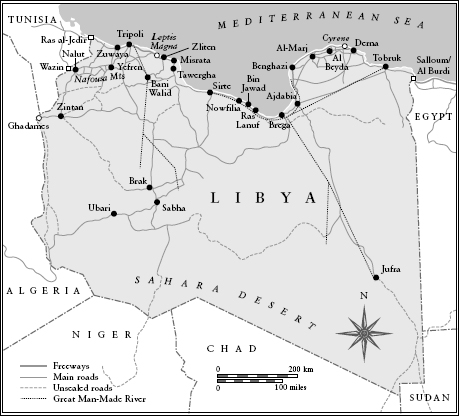

Map William Donohoe. Used by arrangement with Faber and Faber Ltd.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA

Hilsum, Lindsey.

Sandstorm : Libya in the time of revolution / Lindsey Hilsum.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN: 978-1-101-58359-3

1. LibyaHistoryCivil War, 2011 2. RevolutionsLibya. 3. Qaddafi, Muammar. 4. LibyaHistory1969 I. Title.

DT236.H55 2012

961.2042dc23

2012005601

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Designed by Marysarah Quinn

No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the authors rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

ALWAYS LEARNING

PEARSON

In memory of Tarek Ben Halim

19552009

The Ghibli is a hot, dry, usually south to southeasterly dust-bearing desert wind that occurs in Libya throughout the year, but most frequently in spring and early summer. El-ghibli can have profound effect on the landscape by moving vast quantities of sand.

WEATHER ONLINE

Map of Libya featuring major towns, significant places in the 2011 revolution and principal roads

PROLOGUE

There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism.

WALTER BENJAMIN, ON THE CONCEPT OF HISTORY, WALTER

BENJAMIN: SELECTED WRITINGS, 19381940

I will die as a martyr in the end.

MUAMMAR GADDAFI , Tripoli,

FEBRUARY 22, 2011

Colonel Muammar Gaddafi, Brother Leader, Universal Theorist, Falcon of Africa, King of Kings and Supreme Guide of the Great Socialist Peoples Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, met his end as he tried to reach his birthplace of Jahannam in the Libyan desert. One of the hottest places on earth, Jahannam translates as hell, and that is what he went through. Dragged, wounded and bleeding, from a storm drain where he had been hiding under heavy fire, accompanied by his remaining bodyguards and fifth son, Mutassim, he was savagely kicked, punched, sodomized with a metal rod, and eventually shot in the chest and the head. Cheering fighters filmed using their cell phones as their comrades did to Gaddafi what they felt he had done to them for four decades. It was a cruel culmination of forty-two years of brutal and capricious rule and eight months of revolutionary conflict, an act of extreme violence from which a new state would be born, and from which a people who had grown used to dictatorship would have to learn to govern themselves.

The day after Gaddafis death I drove east from the Libyan capital, Tripoli, to the town of Misrata to meet the men who had captured him. The fighters from Libyas third city were the most bitter of the countrys revolutionaries, because they had endured months of siege in which thousands had been killed and wounded, women had been raped and constant bombardment had turned their most modern buildings into blackened skeletons. After Tripoli fell in August the Misrata brigades moved farther east, to Gaddafis hometown of Sirte, which they destroyed as they hunted down the last of his supporters. Some people said the fighter who delivered the coup de grce came from Benghazi, the town in eastern Libya where the revolution had started in February 2011, but it was the men from Misrata who seized and set upon the leader, and claimed his death as their victory.

In front of the mosque where they had celebrated Friday prayers they showed me the Thuraya satellite phone Gaddafi had been carrying, which he had used to call the Syrian TV station that broadcast his last defiant audio messages. It rang once, they said, and they heard the voice of a young woman they thought might be his daughter, Aisha, who had fled the country a few weeks earlier. I was handed a thumb-sized packet tightly wrapped in paper and Scotch tape that they said was an amulet, an African charm that he carried for good luck. Back at the barracks they displayed other artifacts. His bootsblack, with a one-inch heelan assault rifle andprize of prizesGaddafis golden pistol. I picked it up and turned it over. It was extremely heavy and oddly beautiful, embossed with a kind of fleur-de-lis pattern and engraved in Arabic with the words: The sun will never set on Al Fattah Revolution.

It was a moment to reflect on the delusions of power. Al Fattahhe who opens the gate, just as Mohammed opened the gates to Meccawas the name Gaddafi had given the revolution that brought him to power in 1969. The sun had set on it eight weeks earlier, when the fighters took Tripoli and he had fled. Libya was now emerging from the darkness. But Gaddafi was deluded to the last. He was an old-style dictator, a ruthless megalomaniac, but he refused to call himself president, pretending that he had no formal role and that the Libyan people were in charge of their own destiny. His veteran bodyguard, Mansour Dao, hauled out of the drainage ditch with his boss, said Gaddafi had spent his final weeks moving from villa to villa in Sirte, sad and angry, alternating between rage and despair but convinced despite all evidence to the contrary that the Libyan people loved him still.

The brigade that caught Gaddafi said they were not the ones who had killed him. That had been the work of others, who had rushed to the scene as the news of his capture spread. Omar al Sheibani, a small, balding man in plain khaki fatigues, said he had been the first to recognize the wounded dictator as he emerged, bleeding and limping, his speech slurred, from the culvert where he had been hiding after a NATO air strike on his convoy.

Next page