CONTENTS

R UTH ACKROYD WAS in the garden checking the rhubarb when the RAF Spitfire accidentally shot her chimney pot to bits. The shock of it brought the baby on three weeks early.

I was expectun, shed often say, over the years. But I wunt expectun that.

Shed had cravings throughout her pregnancy, ambitious ones: tinned ham, chocolate, potted shrimp, her husbands touch, rhubarb. Rhubarb was possible, though. Ruth and her mother, Win, grew it in the cottage garden. They forced it, which is to say, they covered the plants with upended buckets so that when new tendrils poked through the soil, they found themselves in the dark and grew like mad, groping for light. Stalks of forced rhubarb were soft, blushed, and stringless. You could eat them without sugar, which was rationed, and Ruth wanted to. So shed waddled out into the garden on a rare day of early-spring sunshine to lift the buckets and see how things were doing. See if there was any chance of a nibble.

Win had said, You put that ole coat on, if yer gorn out. Theres a windd cut yer jacksy in half.

Ruth hadnt seen George since his last leave, when, silently (because Win was sleeping, or listening, a thin wall away), hed got her pregnant. Now he was in Africa. Or Italy, or somewhere. There was no way she could imagine his life. He might even be dead. The last letter had come in January:

The last push, or so they say... Cold as hell here in the nights... Hope you and the little passenger are well.

Love, George

Probably not dead, because thered have been a telegram. Like Brenda Cushion had got, six months ago.

Ruth had gone down the garden path with her huge belly in front of her. She was frightened of it. She had little idea what giving birth might involve. Win had told her almost nothing; she was against the whole thing. Knocked up by a soldier: history repeating itself. Nothing good could come of it. The baby had grown in Ruth, struggling and undiscussed. An unspeakable thing. A wartime mishap. The two women had sat the winter out in front of dying fires of scrounged fuel, listening to the wireless, grimly knitting, not talking about it.

Washing blew on the line: tea towels, Ruths yellowish vests, her mothers bloomers ballooned by the wind, their elasticated leg holes pouting.

There were two rhubarb clumps, a rusty-lipped bucket inverted over each. Ruth had leaned, grunting, to lift the first one when all hell broke loose above her head.

The air-raid siren had not gone off. The air-raid siren was a big gray thing the shape of a surprised mouth, mounted on a wooden tower behind the Black Cat Garage, more than a mile away. It made a moan that turned hysterical, then stopped, then started over again, rising in pitch, driving the local dogs mad. Throughout the summer of 1940, it had wailed day and night as the German planes came over, and Ruth and Win had spent terrible long hours in the darkness under the stairs, waiting for it to stop. Or for the riot in the skies to fall upon them and kill them. (Sometimes Ruth couldnt stand it and had gone outside, despite her mothers prayerful begging, to watch and listen to the dogfights in the sky, the white vapor trails scratched against the blue, the black trails of planes falling, the awful hesitations of engine noise that meant one of ours or one of theirs was falling, a man in a machine was burning down.) But on this occasion, the siren remained silent. There had been no German air raids for eighteen months, after all. The war was over, bar the shouting.

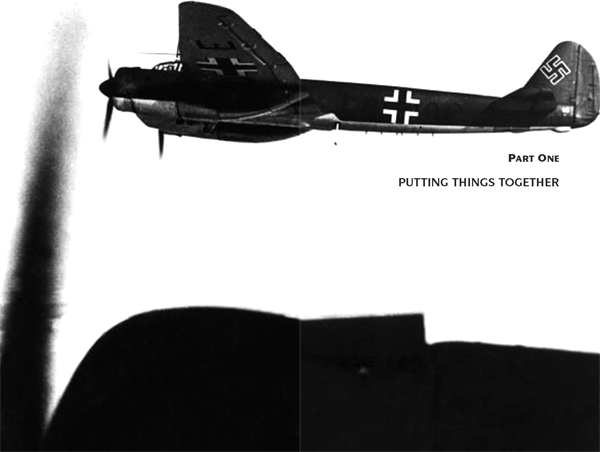

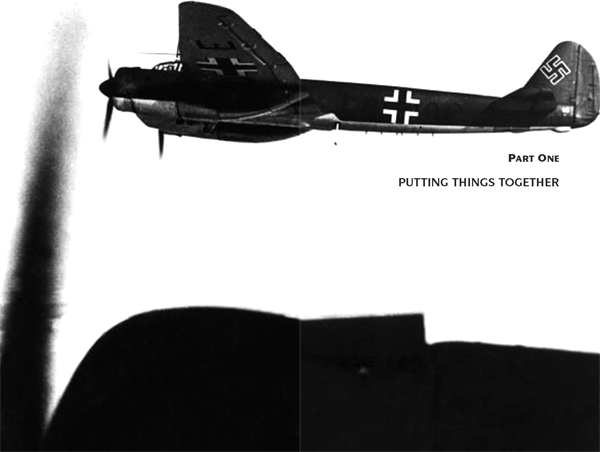

So Ruth was terribly surprised when the chimney pot exploded and the German plane came from behind the elms and filled the garden with savage noise. The machine was so low that she was certain it would plunge into the cottage. She fell backwards with her knees in the air and saw, with absolute clarity, the rivets that held the bomber together and its vulnerable glass nose and the black cross on its fuselage and the banner of fire that trailed from its wing. One of the Spitfires in pursuit was pulling out of a dive. Its underbelly was the same blue as the heavy old pram that Chrissie Slender had lent her. The sound of the planes was so all-consuming that the fragments of the chimney tumbled silently into the yard. Inside their wire run, the hens frenzied.

Y OULL THINK IT fanciful, I suppose, but I blame that German plane for my lifelong dislike of surprises and loud noises. Its an unfortunate dislike, really, because the world, during my long stay in it, has got noisier and noisier. And more and more surprising.

It so happens that I know who flew that Junkers 88 over Bratton Morley, at little more than tree height, on March 9, 1945. Forty years after his suicidal flight, I was in Holland, doing research for a picture book about what were called doodlebugs, the German rocket bombs launched upon England during the last year of the Second World War. In Amsterdam I spent almost a week in a thin and lovely old building full of books and maps and documents and photographs. It was like being in an immensely tall bookcase. On my last day, one of the librarians brought me a book entitled Our Last Days. It was a collection of first-person accounts by German servicemen and civilians of their experiences during the final desperate stage of the war they knew they had lost. I flicked through it and saw the words RAF Beckford, which was the name of the Norfolk air base four miles from where, in an untimely and messy fashion, I was born. I licked my finger and turned the pages back. The piece was a badly written (or poorly translated) story by a former Luftwaffe sergeant called Ottmar Sammer.

I struggle to tell you how I felt when I read it. A bit like looking in a mirror for the first time in years, perhaps.

Here, in my own words, is Sammers story.

Hed spent the last two years of the war in charge of the ground crew of a squadron commanded by Oberst Karlheinz Metz. Metz was, as a pilot, both brilliant and fearless. Hed joined the Luftwaffe at the age of eighteen, and by the time he was twenty, he was dropping bombs on Spanish democrats, thus helping to inspire Picassos Guernica. During the blitzkrieg on Britain, hed flown more raids than any other officer. Once, hed flown his crippled bomber back from Plymouth with all his crew dead. Hed won so many medals that if hed worn them all at once, the sheer weight of them would have made him fall at on his face. (That was the nearest that Sammer came to making a joke.) Metz was also a passionate Nazi. There was a photograph of him in the book. The odd thing was that no matter how long I studied it, I forgot what he looked like as soon as I turned the page. He was weirdly ordinary-looking.

In March 1945, Metzs squadron was stationed in western Holland. His situation was quite hopeless. American and Canadian forces were less than fifty miles from his airfield. He had not flown, nor received any orders, for more than two weeks. Of the twenty-two planes hed originally commanded, only seven still existed. Of those, only three were airworthy. He had, despite his demands, only enough fuel to get one plane to England and maybe back. On March 7 he received a signal from Berlin telling him to destroy his aircraft and retreat his squadron eastward to the German border.