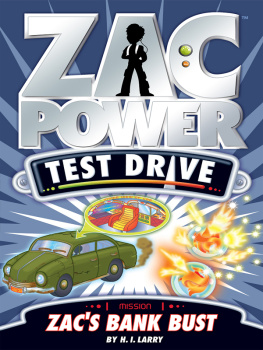

The Great Mars Hill Bank Robbery

Published by Down East Books

An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB, United Kingdom

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

Copyright 2016 by Ronald D. Chase

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Available

978-1-60893-361-7 (paper : alk paper)

978-1-60893-362-4 (electronic)

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

To

Nancy, Eric, Adam, Hannah, and Raina

And in memory of PFC Guy Beanie R. Bean

Died February 23, 1968

Quang Tri Province, Vietnam

Age 21

A friend

Prologue

I first learned of Bernard Patterson and the Mars Hill bank robbery while reading a series of three newspaper articles in the Bangor Daily News during the fall of 1973. His story immediately captured my interest. At the time, I was living in a rented mobile home in Calais, Maine, with my wife and infant son. My career with the Internal Revenue Service had just begun and we were barely subsisting on my sixty-five hundred dollar per year salary. The fascinating, dramatic yet often humorous tale about a fearless former Vietnam War hero turned improbable bank robber, who miraculously escaped to experience a succession of riotous intercontinental escapades while on the lam for nearly seven months was simply unbelievable. I remember thinking his story would rival the most exciting, compelling adventure novel. He seemed to be a real-life version of Don Quixote, Butch Cassidy and Robin Hood all rolled into one implausible package.

In truth, I related to him; and with some reservations, admired him. Both born in 1947, we grew up in working class families in rural Maine communities. Both of us had checkered, generally unsatisfactory public school experiences and ended up in the army as nineteen year olds during the peak of the Vietnam War. At that juncture, our paths varied. Bernard was sent directly into the maelstrom of Vietnam where he experienced several years of combat, while mine was a much more benign exposure with tours of duty in Korea and Alaska. However, like hundreds of thousands of other young men who served during the Vietnam era, we both returned disillusioned, distrustful of our government institutions and with an abiding sense that we no longer fit neatly into the society we had left. His madcap, anti-establishment, albeit criminal, actions seemed to speak for all of us. There appeared to be some convoluted nuance of justice in his escape, the unrestrained, extravagant spending and casual, devil may care approach to the entire process.

I never forgot Bernards adventures. An inveterate storyteller, whenever I travelled through Mars Hill on my way to or from an outdoor expedition in northern Maine or eastern Quebec, I invariably related the unbelievable events of his story to my usually doubtful companions. That Im occasionally prone to embellishing a good story may have contributed to their skepticism. A companion on some of my canoe trips in northern Maine and a frequent victim of my story telling, my youngest son Adam may know the facts as I used to relate them almost as well as I. Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of this tale is that the facts are so incredible they eliminate any need for embellishment.

In January 2013, while on a winter mountaineering trip in New Hampshire, I had a fortuitous encounter with Peter King. Overhearing him talking with a companion about a fellow he had worked with who had robbed a bank in northern Maine and was the most reckless person hed ever met immediately caught my attention. Striking up a conversation, I asked if the bank hed robbed had been in Mars Hill. Affirming that it was, we had an extended conversation about his experiences working and socializing with Bernard. Before it ended, I announced my intent to write a book about him and the robbery.

Peter ended our conversation by stating that he liked and admired Bernard and counted him as a friend. That was an observation that has been regularly repeated by virtually everyone that Ive interviewed who knew him intimately. Bernard was a good and loyal friend who engendered that same fidelity in people who befriended him. He was exceedingly likeable, humorous in a caustically sarcastic manner and despite his actions and behavior perceived to be a good guy. When I first contacted one lifelong friend, his initial response was that he would not be party to anything that degraded Bernard. As much as a half century later people who knew him invariably say, Bernard was a friend.

The late sixties and early seventies was a turbulent period for many in America, but probably none more than returning combat veterans. Dramatic social change rapidly evolving in a constricted timeframe, it was punctuated by strident sometimes violent disagreement over the moral acceptability and strategic value of the Vietnam War. Anti-war sentiment dominated the social and political landscape. Barely men, thousands of rural Maine teenagers like Bernard who entered the service in the mid-sixties left a sheltered world of school dances, conservative values and relatively secure circumstances; although the latter was not true of Bernard. Only the most daring among them had experimented with alcohol or dabbled in sex; and marijuana use was almost nonexistent.

While in the military, particularly Vietnam, many were exposed to a world of hard drugs, pervasive prostitution, corruption, desperate poverty and incomprehensible violence. Bernard experienced all of these in the extreme. However, unlike veterans from previous wars, Vietnam War returnees encountered a very different environment than the one they left; one of changing mores, heavy drug use and hostility toward veterans. Resentments, antisocial behavior and adaptability problems on the part of many veterans often resulted.

The Vietnam War was also unique in recent American history as it was a class war. World War II had been fought by a cross section of young men from all segments of society. This was also true of the Korean War, although to a somewhat lesser extent. For most of the Vietnam War, student draft deferments had the effect of exempting much of the middle and upper classes from service. Although there are no definitively reliable statistics, its generally accepted that in excess of seventy-five percent of the enlisted men who served in Vietnam were from working class or poverty level backgrounds and that only about ten percent of the young men who came of draft age during the Vietnam War actually served in the military. This too fueled resentment among many Vietnam era veterans. By all accounts, Bernard came from financially poor circumstances. Its not surprising that the justification he used for robbing the bank was to forcibly take out a loan after he was reputedly denied college education benefits by the Veterans Administration. He had been promised education benefits and he believed he was entitled to them. Frustrated, he took action.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.