And on the seventeenth day of the seventh month the ark came to rest on the mountains of Ararat.

You mistake the shadows of the mountains for men.

O n the evening of December 7, 1988, in a quiet home at the end of Terryhill Place, a television was illuminated with strange images. I could not appreciate the horror of it all, the fallen buildings and frozen bodieswhat the 6.9 number on the Richter scale meant for a country made of cards. Only from the panic spread upon my fathers face did I realize that something extraordinary was happening to our homeland.

Hayastane ufig e, I said in my first voice. Armenia is hurting. My mother marveled at that infant phrase, but my father did not share the moment with her. He was already gone into the storm of telephone calls that was connecting all the major cities of the Armenian diaspora: Boston, New York, Detroit, Montreal, Paris, Moscow, Beirut, Aleppo, Jerusalem, Tehran, Athens, Sydney, and Buenos Aires. We were in Los Angeles, the command center.

The phone rang all through the night, delivering the burning voices of priests, editors, and doctors to the ears of my father, a rising community leaderbut still, inescapably, the son of the famous professor. Reports were already suggesting that more than fifty thousand people, residents of Soviet Armenias northwestern towns and villages, were dead.

It was all wrong. This was supposed to be a good day. Only a few hours earlier, at United Nations headquarters in New York, Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev had been negotiating the close of a long and cold war. At the same time, on the stage of the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles, my mother had been sworn in as an attorney at law. She had raised her right hand and pledged to defend the Constitution of the United States. Against all enemies, she had said, glowing in the American dream, foreign and domestic.

And just then, seven thousand miles away, the jealous earth had moved under Armenia.

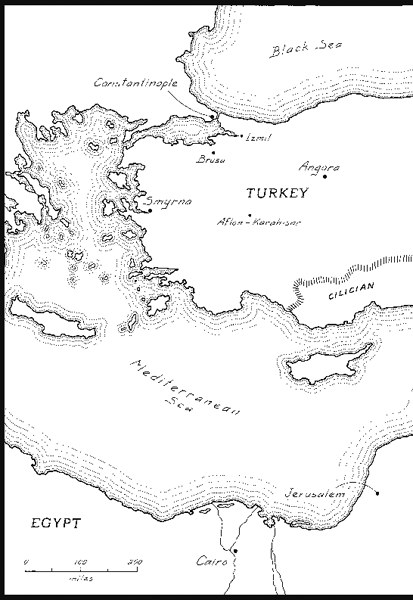

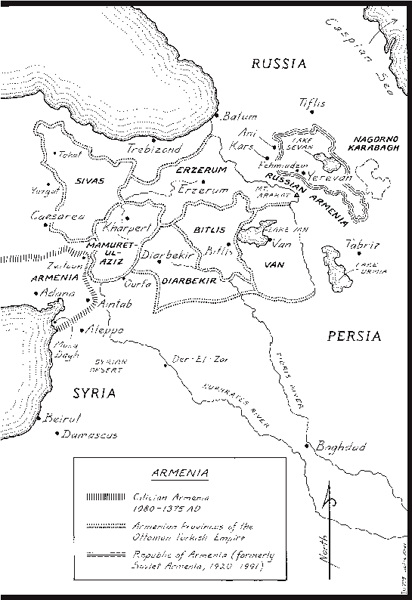

I WOULD BE PLEASED TO recall for you the more glorious moments of our national history, how Tigran the Great once ruled over an Armenian empire stretching from the Mediterranean to the Caspian seas. But that was in the first century B.C., and the truth is that history was not so kind to the Armenians. For millennia they suffocated between Roman and Persian, Byzantine and Arab empires. They lost their kingdoms, their independence, and then their unity.

The Armenian saga unraveled into modernity on separate stages: Turkish Armenia to the west and Russian Armenia to the east. This is a tale of two homelands.

In 1915, under the cover of world war, the ultranationalist Young Turk government erased the Turkish Armenian homeland; a million and a half Armenians were murdered, and a million more escaped to create diasporas of memory around the world. That is where my great-grandparents came fromTurkish, or Western, Armenia.

Russian, or Eastern, Armenia was exempted from the annihilation. As the tsars Petrograd combusted in a Bolshevik revolution, the Armenians of his empire seized an opening in history and declared in 1918 the independent Republic of Armenia. But only two years later, caught between the forces of Turkish nationalism and

Russian Bolshevism, the republics leaders were forced to choose their surrender.

In 1920 the Armenians submitted to the promises of a new government in Moscow. They did not know that in 1923 Joseph Stalin, the peoples commissar for nationalities, would seal the transfer of Mountainous Karabagh (in Russian, Nagorno-Karabagh) and other Armenian lands to neighboring Soviet Azerbaijanthat Armenia, shredded and sovietized, would be shredded again and stuffed into a humiliating thirty thousand square kilometers in the South Caucasus.

It was there, in the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic, that the Eastern Armenians lived for decades, waiting through Malenkov, Khrushchev, and Brezhnev.

Glasnost y perestroika, Mikhail Gorbachev declared from Moscow, openness and restructuring"and the Armenians thought they had been waiting for him. In February 1988 half a million Armenians converged on the streets of Yerevan, their capital city. They appealed to Mikhail the Savior to reunite Mountainous Karabagh with Armenia, and Gorbachev responded a few months later by banning all demonstrations.

In the fall of 1988 the Armenians returned to their homesthinking about their cousins in Mountainous Karabagh and wondering, for the first time, what democracy felt like. Meeting in candlelight, the Armenians sought their fortunes in coffee cups and told stories of freedom in the night.

Gar u chgar. The Armenian fairytales always began with those mysterious words. There was and there was not

T HE A MERICAN T RANS A IR B OEING 727 was carrying six crew members, twenty-one passengers, and more than fifty thousand pounds of medical equipment, food, and blankets. This was an emergency charter flight of the Department of State, yet there they were, Raffi and Vartiter Hovannisian, that curious son-and-mother team, racing to the fatherland.

They were on the same airplane, but Raffi and Vartiter were embarking on two very different journeys. Raffi, a lawyer and activist, was on a mission of hope to the land of his dreams. Vartiter, a doctor, was on a pilgrimage of grief to the Soviet nightmare she had renounced long ago. Her name means rose petal, but occupying her narrow frameunder graying hair and behind precision lenseswas something thornier, more complicated than that.

Raffi had been to the Yerevan airport before, most recently in May, when he had come to participate in the last demonstrations against the Kremlin, before the ban. Upon each arrival, the Russian colonel at customs had searched and questioned the dark, bearded American with the Armenian name. But today there were no questions, only utter confusion among Soviet airport officials who had no choice but to accept the planeloads of foreigners and goodwill that were flooding into their empire.

But then the treesnaked and deadon the road to the hotel. Then the potholes. Then the frozen fields. Then the city, untouched by the earthquake: rectangular cars parked by rectangular buildings. Then the Soviet tanks, soldiers on the streets. The opera house, the scene of the demonstrations, looked to be a hostile military encampment. Citizens walked their capital in silenceout of sorrow or fear, it was their choice. The wrath of heaven and earth had fallen upon the Armenians.

And then Raffi saw them, the great white mountainsthe lesser and greater peaks of Mount Araratglowing vast and eternal just beyond the city, as if they had been freshly painted upon a bleak canvas. Those awesome mountains, where Noahs Ark is said to have landed, had once served as the symbol of a unified homeland. But today, rising through fog and blizzard, Ararat stood as the behemoth boundary between two homelands: a broken Soviet state on one side and the memory of a murdered civilization on the otherreality and dream. Ararat itself was part of the dream. It stood in Turkey, on the other side of the border.