Also by Christopher Merrill

POETRY

Workbook

Fevers & Tides

Watch Fire

Brilliant Water

7 Poets, 4 Days, 1 Book, with Marvin Bell, Istvn Lszl Geher, Ksenia Golubovich, Simone Inguanez, Toma alamun, and Dean Young

Necessities

Boat

After the Fact: Scripts & Postscripts, with Marvin Bell

ESSAYS

The Forest of Speaking Trees: An Essay on Poetry

Your Final Pleasure: An Essay on Reading

NONFICTION

The Old Bridge: The Third Balkan War and the Age of the Refugee

The Grass of Another Country: A Journey through the World of Soccer

Only the Nails Remain: Scenes from the Balkan Wars

Things of the Hidden God: Journey to the Holy Mountain

The Tree of the Doves: Ceremony, Expedition, War

EDITED WORKS

Outcroppings: Selected Writings of John McPhee

The Forgotten Language: Contemporary Poets and Nature

From the Faraway Nearby: Georgia OKeeffe as Icon, with Ellen Bradbury

What Will Suffice: Contemporary American Poets on the Art of Poetry, with Christopher Buckley

The Four Questions of Melancholy: New & Selected Poems, by Toma alamun

The Way to the Salt Marsh: A John Hay Reader

The New Symposium: Poets and Writers on What We Hold in Common, with Nataa

uroviov

uroviov

Flash Fiction International: Very Short Stories from Around the World, with Robert Shapard and James Thomas

TRANSLATIONS

Anxious Moments, prose poems by Ale Debeljak, with the author

The City and the Child, poems by Ale Debeljak, with the author

Even Birds Leave the World: Selected Poems of Ji-woo Hwang, with Won-Chung Kim

Because of the Rain: A Selection of Korean Zen Poems, with Won-Chung Kim

Scale and Stairs: Selected Poems of Heeduk Ra, with Won-Chung Kim

Translucency: Selected Poems of Chankyung Sung, with Won-Chung Kim

The Growth of a Shadow: Selected Poems of Taejoon Moon, with Won-Chung Kim

The Night of the Cats Return, poems by Chanho Song, with Won-Chung Kim

Published by Trinity University Press

San Antonio, Texas 78212

Copyright 2017 by Christopher Merrill

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher.

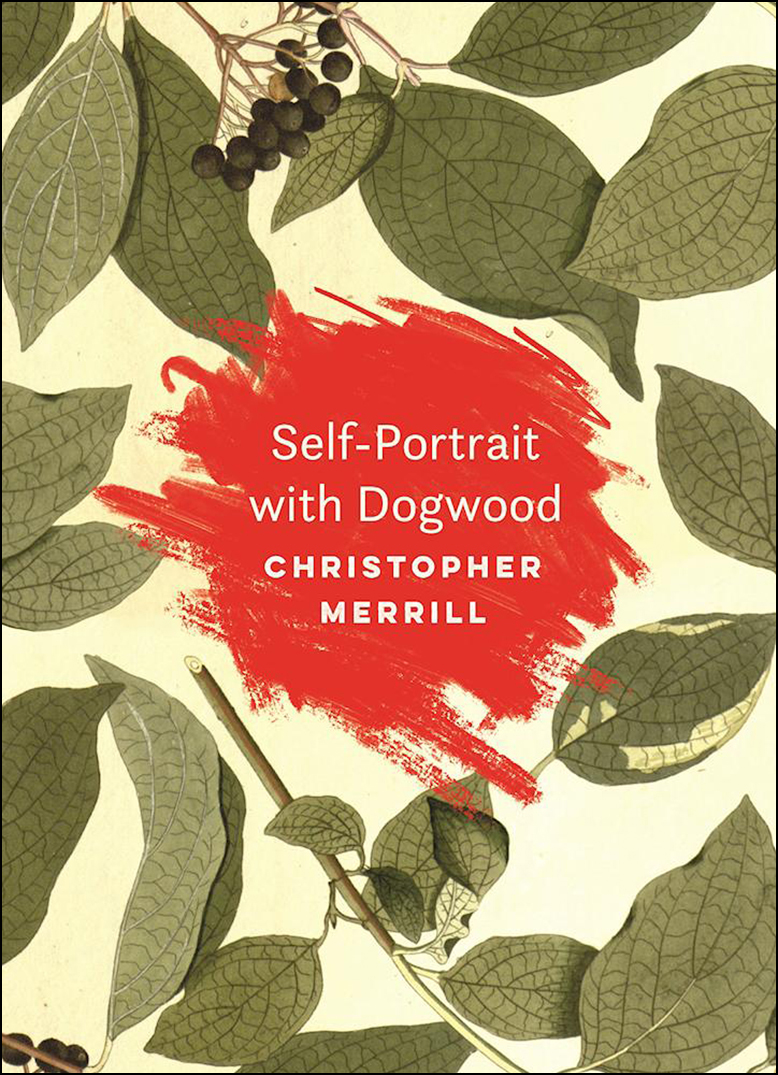

Cover design by ALSO

Book design by BookMatters

Page TK, The Dogwood Trees. Copyright 1978 by Robert Hayden, from Collected Poems of Robert Hayden, edited by Frederick Glaysher. Used by permission of Liveright Publishing Corporation.

ISBN 978-1-59534-810-4 ebook

Trinity University Press strives to produce its books using methods and materials in an environmentally sensitive manner. We favor working with manufacturers that practice sustainable management of all natural resources, produce paper using recycled stock, and manage forests with the best possible practices for people, biodiversity, and sustainability. The press is a member of the Green Press Initiative, a nonprofit program dedicated to supporting publishers in their efforts to reduce their impacts on endangered forests, climate change, and forest-dependent communities.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI 39.48-1992.

CIP data on file at the Library of Congress

21 20 19 18 17 | 5 4 3 2 1

for Tom Gavin

Table of Contents

Guide

Contents

I never saw a tree that was one tree in particular.

ANNIE DILLARD, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek

The average lifespan of a flowering dogwood is eighty years, and at the approach of my sixtieth birthday it occurred to me that I might create a self-portrait in relation to a tree that from an early age I have regarded as a talisman. Not a memoir, strictly speaking, but a literary exploration of certain events through the lens of naturea taking stock of a journey destined to end in the earth. In the course of researching dogwoods, the common name for the woody plants of the Cornus genus found in temperate climates throughout North America, Europe, and Asia, I realized that a number of formative moments in my life had some connection to the tree named, according to one writer, because its fruit was not fit for a dog. In the nursery trade, dogwoods are called ornamentals, their flowering a highpoint of spring. But they serve critical functions in the ecosystem, and since they have informed so much of my life it seemed to me that an extended meditation on the intersection between personal and natural history might hold interest, if for no other reason than to offer a different way of thinking about the tradition of writing memoirs.

A small deciduous tree, the flowering dogwood belongs to the understory in a hardwood forest, occupying the middle space between the ground and sky, providing nectar for pollinating insects, branches and foliage and fruit for perching and nesting songbirds, nutrients for the soil, ingredients for medicines, wood for bowls and shuttles and tools, and an open invitation for an aging man to reflect on his walk in the sun, to reconsider his relationship to nature, to pay attention to the worlds revolving in his memory, his imagination, and all around him.

I built a fort under the dogwood tree, at the edge of the woods separating our property from the road to the Wrights house. Mr. Wright was a Native American (Mohawk, if memory serves, not Lenni-Lenape, the original inhabitants of northern New Jersey), which barely figured into my calculations when I played war with his son Michael, our childhood being framed by the Cuban missile crisis and Vietnam. Our battles were waged between Russians and Americans, not cowboys and Indians; from the base of the dogwood, in a trench dug with sticks and stocked with Fritos, I took aim at my friend, who was hiding in the brambles, aiming at me.

Both Michael and his older brother, John, spoke with lisps, which I held against them. I never liked John, who was not athletic, and when I was cruel to Michael, who was a little weaker than I, they would run and tell their father. He was a lean, dark man with heavily lined features and veins popping out of his arms; his sons attributed this to hard work. Indeed he was always in his yard, cutting the grass, raking leaves, keeping an eye on us. I feared his gaze, even as I hoped that one day veins would pop out of my arms too.

In the meantime I roamed around our village, a patchwork of forests, dairy farms, and houses, some dating to the colonial era, crisscrossed by streams flowing from the surrounding hills. I explored the shuttered iron and mica mines and the remains of forges, kilns, gristmills; fished for suckers in the brook by the baseball field; unearthed arrowheads in the tracks where the Rock-A-Bye-Baby Railroad used to run. Down the road from my grandparents place, in Jockey Hollow, was the Wick House, which had a story. A zigzagging split-rail fence bound the field north of the house, where a hundred soldiers from the Continental Army lay buried, victims of disease and the harshest winters of the Revolutionary War. The most consequential insurrection on the road to independence took shape here, which in turn gave Captain Henry Wicks youngest daughter, Tempe (short for Temperance), an occasion to become a war heroine.