ABOUT THE AUTHOR

James B. Conroy , a trial lawyer in Boston for more than thirty years, is the author of Our One Common Country: Abraham Lincoln and the Hampton Roads Peace Conference of 1865 (Lyons Press, 2014), a finalist for the Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize for 2014. Conroy served on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C., as a House and Senate aide in the 1970s and early 1980s, and earned his JD degree from the Georgetown University Law Center in 1982. He and his wife, Lynn, are the parents of two grown children and the grandparents of two young boys.

Conroy is an elected fellow of the Massachusetts Historical Society and a member of the Boston Bar Association. He lives in Hingham, Massachusetts, on Bostons South Shore, where he serves as a member of the Hingham Historical Commission, and the Community Preservation Committee, has coached youth baseball and basketball teams, and has chaired the Towns Advisory Committee, which advises the Hingham Town Meeting, an exercise in direct democracy through which the Town has governed itself since 1635.

Learn more about the author at his website, www.jamesbconroy.com.

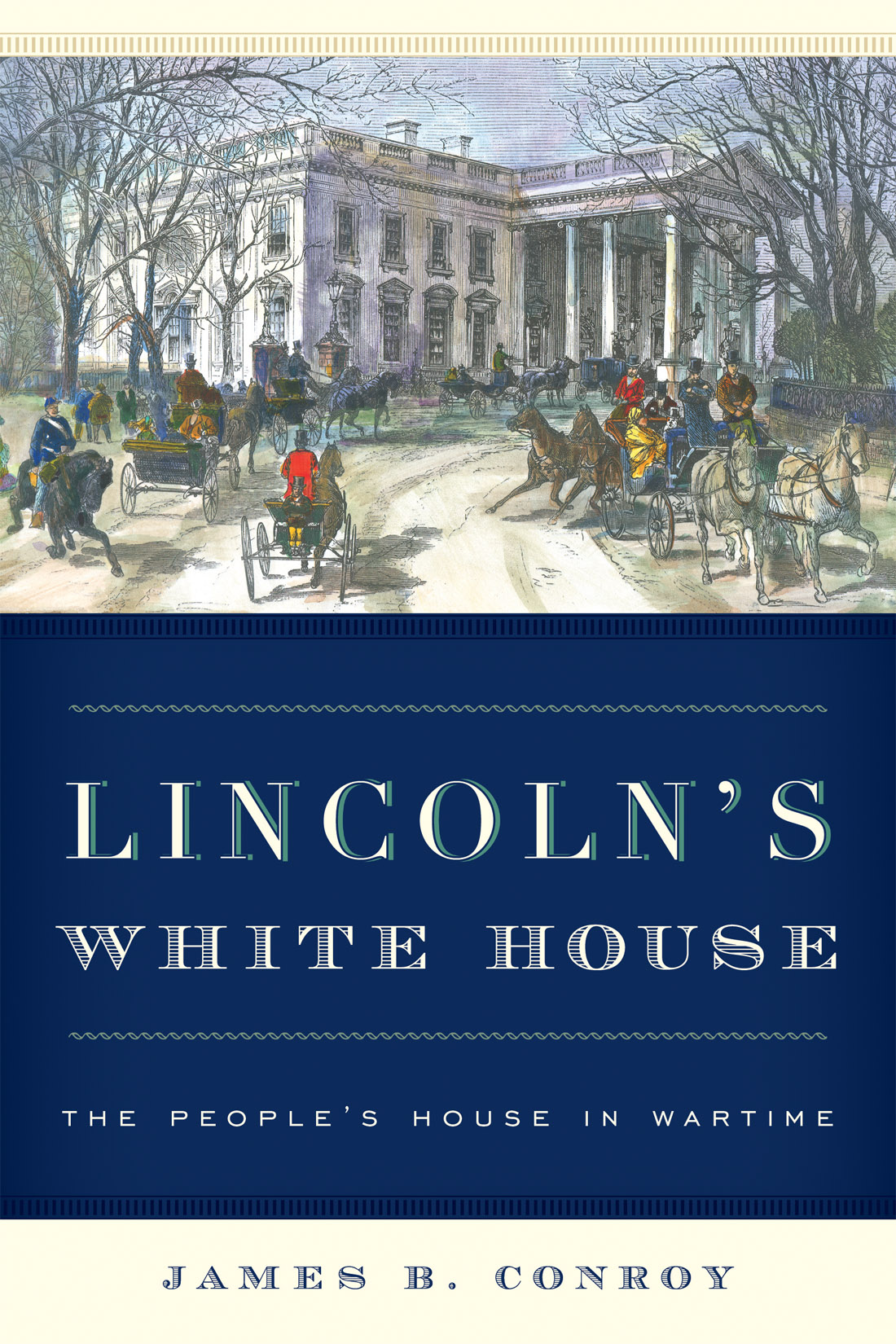

LINCOLNS WHITE HOUSE

Published by Rowman & Littlefield

A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 2634 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

Copyright 2017 by James B. Conroy

All rights reserved . No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Available

978-1-4422-5134-2 (cloth)

978-1-4422-5135-9 (electronic)

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.481992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.481992.

Printed in the United States of America

For Flynn and Tiernan

INTRODUCTION

L ate on a winter night in 1864, the massive White House gates on Pennsylvania Avenue stood open to the world. Just inside both entrances, a pair of stoic cavalrymen sat mounted face to face across the gravel carriageway on the matched black horses of the Union Light Guard. It was not an easy watch. Sitting quietly on horseback for two hours on a cold night is, to say the least, disagreeable, a guardsman later said, but the view was agreeably calm. Barren trees spread their limbs in the dark, a few of the houses windows shone with yellow-tinged gaslight, and flickering jets of flame lit the curved stone path to the white-pillared portico, washed in a pale gold glow. Two sentries paced their beat a few feet in front of the mansion, starting at opposite ends and crossing in the middle with muskets on their shoulders and deer tails on their hats. Said to be more ornamental than useful, neither the Pennsylvania Bucktails nor the Union Light Guard challenged any sober citizen who approached the Presidents House.

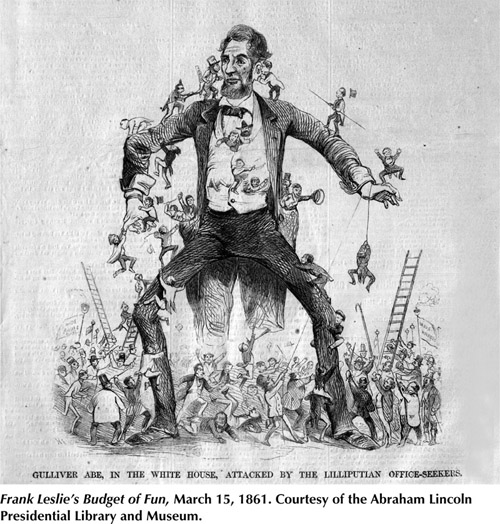

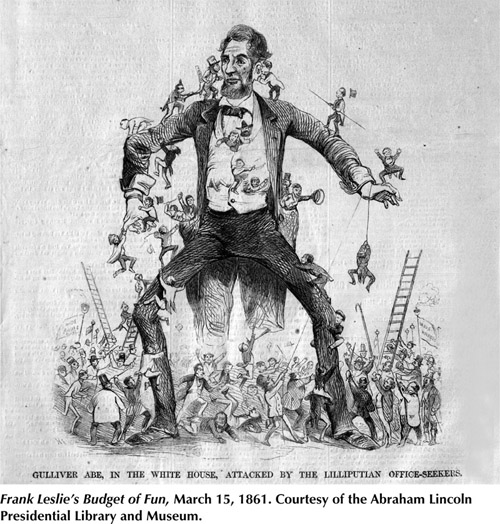

Leaning on a pillar under the portico, a bright young corporal named Robert McBride, fresh from Ohio with the rest of the Union Light Guard, heard the front door open, and a tall, thin, awkwardly moving man came out alone, looking weary in a long black coat and a poorly kept stovepipe hat. McBride had seen his face in Harpers Weekly and Frank Leslies Illustrated Newspaper , but the gaslight caught the furrows that the portraits left out.

As Lincoln closed the door, clasped his hands behind him, and slowly crossed the portico with his head bent forward and his eyes cast down, McBride drew his saber to his chin, and the nearest Bucktail sentry presented arms, but the commander in chief noticed neither mans salute. Alone with his burdens, directly under the gaslight as if he were on stage, he paused at the top of the steps for what seemed like minutes, long enough for McBrides arm to quiver. Then he absently lifted his hat to his guards and walked to his left toward the War Department down a wooded, brick-paved path barely lit by a single flame. McBride sheathed his sword, the sentry resumed his beat, and they both watched the president anxiously as he passed into the shadows of the trees.

Back on duty the next morning, McBride saw Lincoln leave the White House again and start toward the War Department. The Bucktail sentry swung his musket to his chest in a rigid salute, but the president passed him by as if he were invisible. Lincoln had walked a dozen paces down the path before he stopped short, turned around, raised his hat, and bowed like one gentleman apologizing to another for an unintentional slight. Only then did the soldier resume his beat.

After Lincoln was out of earshot, McBride asked the Bucktail why he had held his position after the president passed. Lincoln ignored his salute all the time, the sentry said, but he always stopped and returned it before he had gone very far, alone on his walk through the trees at the height of a civil war.

Later that year, a British writer and a fellow Englishman approached the White House with an editor of the New York Times and found not a dog on the watch. Lincoln had not yet arrived for their meeting, but his wartime home and headquarters were as open as a barn. Passing freely through the portico, the editor took the Londoners into the lobby, led them up the stairs past a servant who was cleaning them, and walked them into the office of the President of the United States as if it were a shop. His British companions followed in mute amazement, half ashamed of treading unasked on this sacred ground, but the American had no such qualms. The people paid for this house, he said, and they had a right to see the inside of it; they paid the President to live there, and they had a right to see him in it.

The Presidents House is not his castle, the Englishman told his readers; it is not even his house.

Many years ago, a distinguished professor of medieval history wrote a note on a paper I had worked hard to write, a rare event in my misspent youth. He called it a very good job. Faint praise, it seemed to me. You have done your research carefully, he wrote, and written it quite well, though so many short paragraphs indicate a little weakness in organization. I could have lived with a little weakness, and I still like digestible paragraphs. It was the last line that stung: History is inquiry, engaging with the past, which we engage in because it has a purpose. You have not indicated your purpose. B + .

The professor was a kindly man, and he made me a generous offer. If I gave him a revision that stated and served a purpose, the paper might earn an A. I cannot recall the purpose, but I do recall the A, and the lesson that went with it. Thousands of books on Lincoln, including one of my own, have blessed and burdened the world. No one should write another unless it has a purpose.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.481992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.481992.