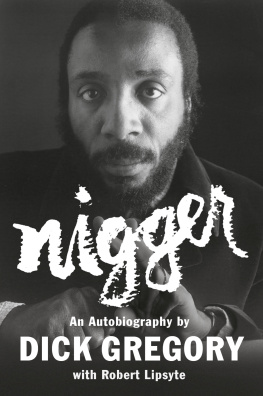

Separated by almost exactly one century, two significant events were responsible for capturing the minds of Americans and creating the man we would all come to know as the one and only Dick Gregory. The first was the raid on Harpers Ferry by famed abolitionist John Brown in October 1859, which was often called the dress rehearsal or tragic prelude to the American Civil War. The second was the publishing of a remarkable article in Ebony magazine in October 1960 entitled Why Negro Comics Dont Make It Big, in which Dick Gregory was mentioned for the first time on the national stage as a mere newcomer.

To most historians, comedians, and students of the Black experience in America, these events appear to represent two fundamentally unrelated circumstances in the shaping of our country as we know it. However, every year on Dick Gregorys birthday, a date which almost perfectly aligns with John Browns October raid, Dick Gregory would visit Harpers Ferry in memoriam. On every second of December, he would go to Charles Town, Virginia (now in West Virginia), and hug the tree where John Brown was hanged. I hug the tree for the white man who gave up his life for the Black man, he said. There are trees all over the world. Lots of other places have trees. What they do not have that [this] tree has is [the spirit] of John Brown. Without the historic raid on Harpers Ferry, without the death of John Brown and the end of the enslavement of Black people in America, we might not have ever heard the name Dick Gregory or seen it introduced to the world in that Ebony article one century later.

Everyone knows that the 1960s were a tumultuous time in our nations history, but few people know that even comedy itself was segregated between Blacks and whites. In that same Ebony article, one white club owner would say, I am very apprehensive about booking Negroes into my club. I dont want a Negro comedian entertaining whites at the expense of Negro people. The famed television star Steve Allen even more poignantly stated, One reason that there is a shortage of Negro stand-up comedians or humorists is that comedy of this sort usually involves a certain amount of critical observation and our society is probably not civilized enough yet to permit or encourage the Negro comedian to make satirical commentary about Eisenhowers golf game, our bungled international relations, the Un-American Activities Committee or other things of that sort. Steve Allen would go on to conclude, Just imagine a Negro comic getting up on stage and saying some of the things that Lenny Bruce or Mort Sahl are getting away with.

Barely three months after the publication of this story, Dick Gregory, the so-called newcomer, would prove Steve Allen wrongor right, depending on your point of viewand wrap all of the prejudicial conjecture, race theory, and misfired predictions of critics and TV stars into the palm of his hand, then take the mic on the biggest stage possible in those days, The Jack Paar Show on NBC.

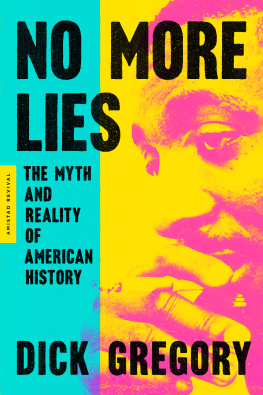

At the outset of my six-year journey to bring the incredible life story of Dick Gregory to film, I was vastly unaware of the immense complexity behind Dick Gregorys brand of humor. Throughout his life, Dick Gregory was often made an example of, sometimes by his own design; Black folks projected our woes onto him, and white folks cherishedor reviledhim for shining a mirror on their own prejudice.

For me, the personal experiences of Dick Gregory were like listening to a walking history lesson. It took only a few hours into my journey to make this film for me to realize that Dick Gregory was one of a kind, and I became totally consumed. In 1975, Dick Gregory quit comedy, staging his last nightclub performance at Pauls Mall in Boston, Massachusetts. The announcer who introduced Dick Gregory read a letter from his publicist, Steve Jaffe, that highlighted the power of his contributions to society. One passage went like this: No man has given more, asked less, or been more needed. Albeit only a brief summation of the gifts of Dick Gregory, I can think of no more prescient a phrase to describe what he would come to mean to the world.

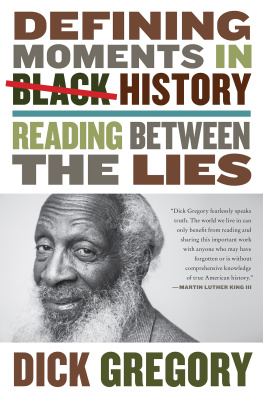

Dick Gregory is often credited as being a civil rights activist, and although it may have started that way, civil rights, like comedy, was never his terminus. Yes, he was an activist, but more appropriately, he was an advocate and protector of human rights. Thus when the time came to create a graphic for the poster to represent the film, none was more fitting than that of Dick Gregory, sitting center stage, illuminated by infinite silhouettes of himself in the different colors of the rainbow. The array of colors represents to me not only the many lives that Dick Gregory lived but also his aura. While he walked the Earth as a Black man, talked and thought as a Black man, he could feel like everyman, and his spirit, heart, and empathy toward all mankind are what made him the great teacher, guru, adviser, and friend he became to me and the world. When you combine all of those colors together, it produces the white light as projected by the sun, and no one better understood the power of the sun, or how to use it as a force of good and righteousness, than Dick Gregory.

Andre Gaines, producer and director, The One and Only Dick Gregory

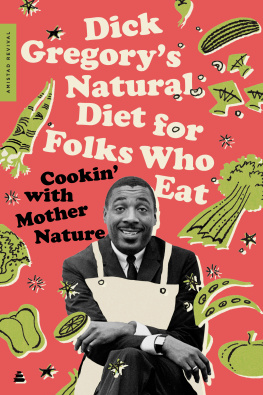

What a life, what a blessing. Dick Gregory was many thingshe metamorphosed from athlete to comedian to activist to presidential candidate to nutritionist to social criticat no point leaving behind the nucleus holding him together: love. Lovelove for self, love for thy neighbor, love for humankind, love for naturewas the engine that powered his many manifestations.

Metamorphosis is a change of the form or nature of a thing or person into a completely different one, by natural or supernatural means. Its typically brought about by both internal and external forces. The sum of these forces produces a new manifestation that advances its previous form. At every iteration, Dick Gregory was passionate about life, laughter, and equality. There was not a righteous movement in his lifetime that his blood, sweat, or tears didnt impacthis activism was rooted in love and dignity.

Richard Claxton Gregorys life was incredibly well-lived. My colleagues and I studied his mind like the science it often was. Weve extrapolated from his lifetime the building blocks and experiences that help explain his unyielding life of service. Generations will delve into his sacrifice, comedic genius, focus, and aptitude. Civil rights, womens rights, childrens rights, human rights, disabled rights, animal rights... Dick Gregorys DNA is on virtually every movement for fairness and equality for all living things on this planet. He taught us the power of love by example.

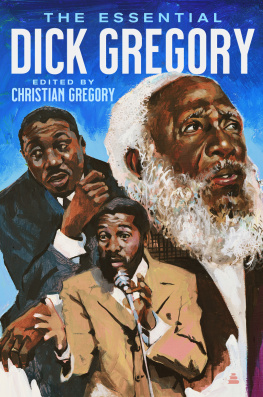

Dick Gregory was always busy but never hurried. He made time for everyone and almost everything. He wrote a lot but talked more. He left us so much to pore over, including sixteen books, twelve albums, hundreds of interviews and syndicated news columns, and hundreds of hours of archival footage. The challenge we faced was whittling down this extraordinary amount of material to present in a succinct structure.

We were able to organize this book into three primary sectionsThe Body (covering his early life from 1932 to 1960), The Mind (discourse related to his early career, from 1961 to 1970), and The Spirit (later career thoughts and work from 1971 to 2017)to highlight the periods in his life where his aptitude and brilliance evolved. With the exception of the headnotes, which provide orientation and historical positioning, everything was written or said by Dick Gregory in his own unique style, tempo, and cadence.

The highlights of Dick Gregorys life are well known. However, the ebbs and flows were lost in the brightness of the peaks. More often than not, the real lessons are in the journey. Im delighted to have you take this journey with us. I trust youll be as uplifted and inspired as we were cultivating and compiling this collection.