This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.picklepartnerspublishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books picklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1956 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2015, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

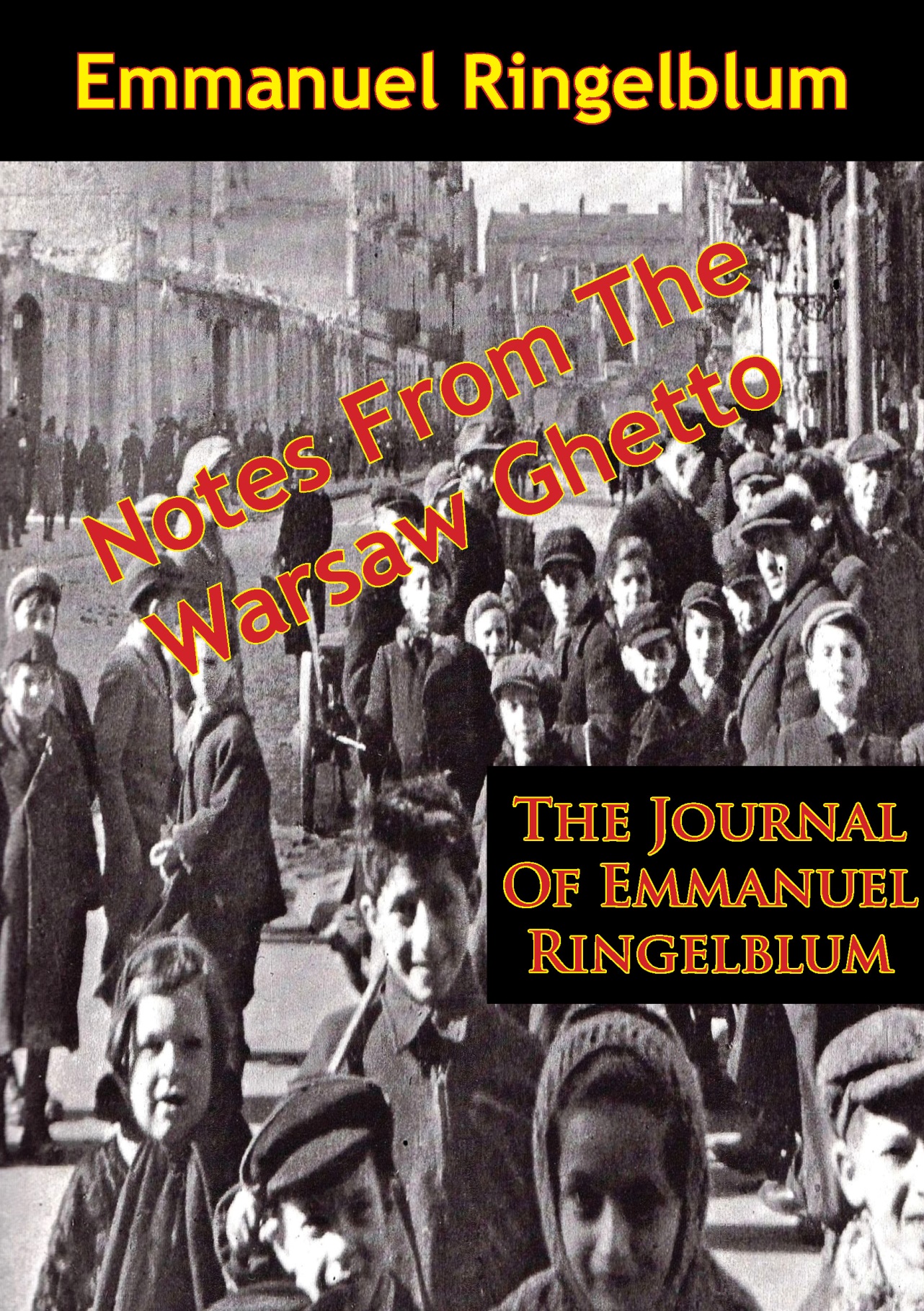

NOTES FROM THE WARSAW GHETTO: THE JOURNAL OF EMMANUEL RINGELBLUM

TRANSLATED AND EDITED

BY

JACOB SLOAN

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Parts of this book originally appeared in Midstream, Winter, 1956. I am indebted to that periodical for permission to reprint the material.

Dr. Philip Friedman, Miss Dina Abramowicz, and Mrs. Rose Klepfisz gave me valuable advice and assistance. The archives of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in New York were kind enough to make available for reproduction the photograph of Emmanuel Ringelblum and the maps of the Warsaw Ghetto and Poland reproduced in this volume.

Jacob Sloan

This English version of Notes from the Warsaw Ghetto is based upon the selection printed in Bleter Far Geszichte , Warsaw, March, 1948, and in the volume published by the Jewish Historical Commission of Warsaw in 1952. Unfortunately, it was impossible to secure access to the full text, either the original in Warsaw or the copy in Israel.

INTRODUCTION

To millions of people, the Warsaw Ghetto will remain forever a symbol of mans inhumanity to manand of the heroic resistance of the human spirit. For within these walls, in an area of about 1,000 acres, or 100 square city blocks, some half million Jews were methodically ground to death in the course of less than three years. Yet, at the end of that time, when more than 90 per cent of the Ghettos residents had been sent to their fate in extermination camps, armed resistance broke outresistance so fierce that a regular German army group was required to put it down. The German army leveled the Ghetto to the ground; nothing remained but rubble and what the Nazis could not extirpatethe memory of those dread days.

It is that memory that has been preserved in the Notes from the Warsaw Ghetto. These Notes are the day-to-day eyewitness account by the man who was the best equipped to keep that account: Emmanuel Ringelblum, the archivist of the Warsaw Ghetto.

He was a man ideally fitted for the task he set himself in November, 1939, two months after the Nazis had overrun Polandto record the whole story of the Jewish catastrophe for posterity. Born in 1900, Ringelblum had already established himself as one of the most promising of the Young Historians group in Warsaw when World War II broke out. He had written four books and innumerable monographs. Significantly, these were all based on research into original sourcesdespite the difficulties Ringelblum encountered in digging up authentic records. He spent tedious hours poring over dusty court records and minutes of council meetings for his works on the role that Jews played in the Kosciusko revolt of 1794, and on the history of the Jewish Community Council in Warsaw in the eighteenth century. Everywhere he looked for the vivid, personal detail that could illuminate the human meanings of the past. For Ringelblum was a social scientist in the larger sense of the word. He had begun his studies as an economist, later turned to sociology, and finally concentrated on history, while still retaining the tools of economics and sociology. He was a social historian, rather than a political scientist; he saw history as primarily the interplay of social, economic, and institutional forces, and only secondarily as the effects of the actions of powerful individuals.

But if Ringelblum had been only a social historian, however talented, if he had not been deeply immersed in the experience of his generation, we would not have had the Notes. For these, as their author repeats time and again, are not the observations of a single man. They are one mans cullings from the experiences and information supplied by a large groupseveral dozensof people from various backgrounds. For Ringelblum was by conviction an active practitioner of popular education, a communal worker, a political party member, a dedicated man of the people.

Emmanuel Ringelblums personal history is instructive. At eighteen, he was living with his parents in the small town of Nowy Soncsz, at the foot of the hills in Western Galicia. He was attending a gymnasium, the European cross between a high school and a junior college. His family, formerly well-to-do, was now impoverished, and Ringelblum had to work his way through school. His days were full. All morning and until two in the afternoon he studied at the gymnasium; then he tutored other students. Of course, he had his own school work to do. But, before turning to it, he spent several hours every day at a self-education group conducted by the branch of the Labor Zionist movement he belonged to. But he was not content with self-improvement; Ringelblums social conscience drove him to organize evening courses for working men and for the pietistic Orthodox youth, the Chasidim, whose learning was completely theological.

In the fall of 1919, Ringelblum left home and enrolled at the University of Warsaw. There he continued the same patternthe classic pattern of the poor university student precariously earning his own keep. Again, he showed himself to be exceptionally social-minded. Evenings he taught courses subsidized by the Central Jewish School Organization of Poland (CJSO). The pay was meager; many days Ringelblum literally went hungry. But he was an idealistic teacher, and he quickly made his influence felt through sheer weight of character. Soon he became the principal of a large evening school in Warsaw; then, chairman of the educational council for all the five evening schools. He was the favorite of the many hundreds of young workers who attended these schools after working hours. In addition, he organized an extracurricular central club for all evening students, meeting Saturday afternoons and evenings when there was no class. He ran meetings, lectures, special-interest classes. His enthusiasm was infectious.

All this time, Ringelblum was attending the University of Warsaw. There, too, he involved himself in extracurricular projects. He led the fight of the General Academic Federation of Jewish Students to induce the government to reduce tuition fees. He also was active in the Federations self-aid organization, which maintained a cooperative kitchen, free loan society, and the like. And then, from 1920 to 1927, he was on the central committee of the Labor Zionist Young Workers Federation of Poland, and published in its journals.

Next page