West of Here

ALSO BY JONATHAN EVISON

All About Lulu

West of Here

A NOVEL BY

Jonathan Evison

Published by

Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill

Post Office Box 2225

Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27515-2225

a division of

Workman Publishing

225 Varick Street

New York, New York 10014

2011 by Jonathan Evison.

All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

Published simultaneously in Canada by

Thomas Allen & Son Limited.

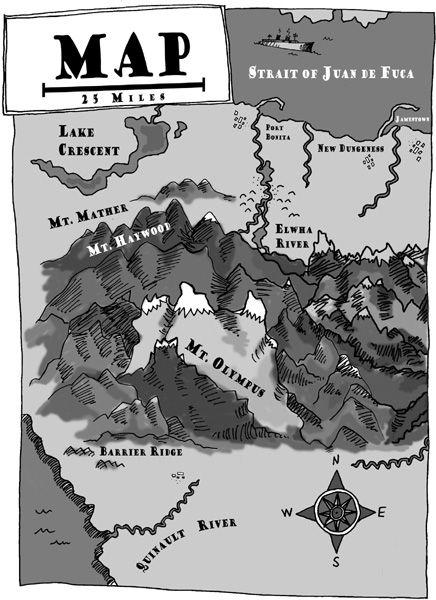

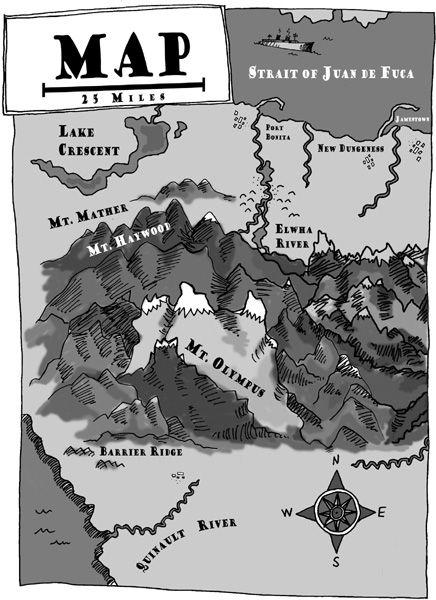

Maps by Nick Belardes.

This is a work of fiction. While, as in all fiction, the literary perceptions and insights are based on experience, all names, characters, places, and incidents either are products of the authors imagination or are used fictitiously.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Evison, Jonathan.

West of here : a novel / by Jonathan Evison. 1st ed.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-56512-952-8

1. Washington (State) Social life and customs

Fiction. I. Title.

PS3605.V57W47 2011

813.6 dc22 2010020224

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

First Edition

For Carl,

who I think wouldve liked this one.

I will sing the song of the sky.

This is the song of the tired

the salmon panting as they fight the swift current.

I walk around where the water runs into whirlpools.

They talk quickly, as if they are in a hurry.

Potlatch song

West of Here terra incognita

footprints

SEPTEMBER 2006

Just as the keynote address was winding down, the rain came hissing up the little valley in sheets. Crepe paper streamers began bleeding red and blue streaks down the front of the dirty white stage, and the canopy began to sag beneath the weight of standing water, draining a cold rivulet down the tuba players back. When the rain started coming sideways in great gusts, the band furiously began packing their gear. In the audience, corn dogs turned to mush and cotton candy wilted. The crowd quickly scattered, and within minutes the exodus was all but complete. Hundreds of Port Bonitans funneled through the exits toward their cars, leaving behind a vast muddy clearing riddled with sullied napkins and paperboard boats.

Krig stood his ground near center stage, his mesh Raiders jersey plastered to his hairy stomach, as the valediction sounded its final stirring note.

There is a future, Jared Thornburgh said from the podium. And it begins right now.

Hell yes! Krig shouted, pumping a fist in the air. Tell it like it is, J-man! But when he looked around for a reaction, he discovered he was alone. J-man had already vacated the stage and was running for cover.

Knowing that the parking lot would be gridlock, Krig cut a squelchy path across the clearing toward the near edge of the chasm, where a rusting chain-link fence ran high above the sluice gate. Hooking his fingers through the fence, he watched the white water roar through the open jaws of the dam into the canyon a hundred feet below, where even now a beleaguered run of fall chinook sprung from the shallows only to beat their silver heads against the concrete time and again. As a kid he had thought it was funny.

The surface of Lake Thornburgh churned and tossed on the up-river side, slapping at the concrete breakwater. The face of the dam, hulking and gray, teeming with ancient moss below the spillway, was impervious to these conditions. Its monstrous twin turbines knew nothing of their fate as they hummed up through the earth, vibrating in Krigs bones.

Standing there at the edge of the canyon with the wet wind stinging his face, Krig felt the urge to leave part of himself behind, just like the speech said. Grimacing under the strain, he began working the ring back and forth over his fat knuckle for the first time in twenty-two years. It was just a ring. There were eleven more just like it. Hell, even Tobin had one, and he rode the pine most of that season. Krig knew J-man was talking about something bigger. J-man was talking about rewriting history. But you had to start somewhere. When at last Krig managed to work the ring over his knuckle, he held it in his palm and gave pause.

Well, he said, addressing the ring. Here goes nothin, I guess.

And rearing back, he let it fly into a stiff headwind, and watched it plummet into the abyss until he lost sight of it. He lingered at the edge of the gorge for a long moment and let the rain wash over him, until his clinging jersey grew heavy. Retracing his own steps across the muddy clearing toward the parking slab, Krig discovered that already the rain was washing away his footprints.

storm king

JANUARY 1880

The storm of January 9, 1880, dove inland near the mouth of the Columbia River, roaring with gale-force winds. It was not a gusty blow, but a cold and unrelenting assault, a wall of hyperborean wind ravaging everything in its northeasterly path for nearly four hundred miles. As far south as Coos Bay, the Emma Utter, a three-masted schooner, dragged anchor and smashed against the rock-strewn coastline, as her bewildered crew watched from shore. The mighty Northern Pacific, that miracle of locomotion, was stopped dead in its tracks in Beaverton by upward of six hundred trees, all downed in substantially less than an hours time. In Clarke County, windfall damage by mid-afternoon was estimated at one in three trees.

Throughout its northeasterly arc, the storm gathered momentum; snow fell slantwise in sheets, whistling as it came, stinging with its velocity, gathering rapidly in drifts against anything able to withstand its force. In Port Townsend, no less than eleven buildings collapsed under the rapid accumulation of snow, while some forty miles to the southwest, over four feet of snow fell near the mouth of the Elwha River, where, to the consternation of local and federal officials, two hundred scantily clad Klallam Indians continued to winter in their ancestral homes, in spite of all efforts to relocate them.

It is said among the Klallam that the world disappeared the night of the storm, and that the river turned to snow, and the forest and mountains and sky turned to snow. It is said that the wind itself turned to snow as it thundered up the valley and that the trees shivered and the valley moaned.

At dusk, in a cedar shack near the mouth of the river, a boy child was born who would come to know his father as a fiction, an apparition lost upriver in the storm. His young mother swaddled the child in wool blankets as she sat near a small fire, holding him fast, as the wind whistled through the planks, setting the flames to flickering and throwing shadows on the wall.

The child remained so still that Hoko could not feel his breathing. He uttered not a sound. A different young mother might have unwrapped the infant and set her cool anxious fingers on his tummy to feel its rise and fall. But Hoko did not bother to check the childs breathing. She merely held it until her thoughts slowed to a trickle and she could feel some part of herself take leave; and she slept without sleeping, emptied herself into the night until she was but a slow bleating inside of a dark warmth. And there she remained for several hours.

In the middle of the night, the child began to fidget, though still he did not utter so much as a whimper. Hoko gave him the breast, and he clutched her hair within tiny balled fists and took her nourishment. Outside, the snow continued in flurries, and the timber creaked and groaned, even as the wind abated near dawn.

Next page