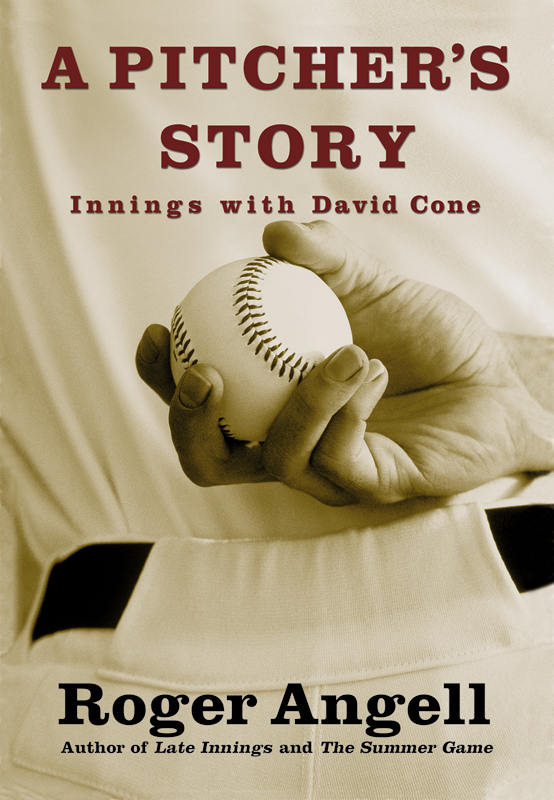

Copyright 2001 by Roger Angell

All rights reserved.

Warner Books, Inc., Hachette Book Group, 237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017, Visit our Web site at www.HachetteBookGroup.com.

First eBook Edition: May 2001

ISBN: 978-0-446-55422-0

Text design by Stanley S. Drate/Folio Graphics Co. Inc.

ALSO BY ROGER ANGELL

Books on baseball: The Summer Game, Five Seasons, Late Innings, Season Ticket, Once More Around the Park

The Stone Arbor (stories) A Day in the Life of Roger Angell (casuals)

Editor: Nothing But You: Love Stories from The New Yorker

Perfection

T he shortstop, Orlando Cabrera, up at bat for the third time, swings and lifts a little foul fly off to the left of the infield. The pitcher, hurrying off the mound, watches the ball anxiously, pointing up at it, and shoots a glance over at his third baseman. Yes, this ball will be caughtit's the last outand when the pitcher, David Cone, takes in the moment he sinks to his knees with his head flung back and his hands up above his ears. It's over. In an instant he will be rushed and ganged by his teammates, converging from the field and flooding across from the dugout, but the scenethe ball in the air and the pitcher unexpectedly falling into an attitude of worshipis already fixed in baseball time, there with Carlton Fisk dancing up the first-base line and gesturing wildly to keep his shot fair; Willie Mays with his back to us, looking up over his head to gather Vic Wertz's drive at the Polo Grounds center-field wall; or, for that matter, Don Larsen pitching to Dale Mitchell here at Yankee Stadium (the old Stadium then), with the numbers, all zeroes, enormous on the black scoreboard behind him. Larsen is back today, as it happens; so is his catcher in that game, Yogi Berra. This stuff can't be happening.

Cabrera, the ninth batter in the order for the Montreal Expos, who have just been beaten by the Yankees, 6-0, in this perfect gameno hits, no runs, nobody on basehas foreseen his role in this freeze-frame as far back as the sixth inning, when, looking at the man on the mound and then counting the depleting outs and innings ahead, he sensed that he could be the final batter of the day. And Cone, for his part, will come to believe that he unconsciously picked up that ecstatic, down-on-his-knees-and-head-to-heaven victory posture from watching some center-court Wimbledon winner on television, long ago, and tucking the picture away in his mind. You always wonder how you'll look when the time comes, he says. Players talk about stuff like this among themselves, believe it or not. You want to be ready. He can't decide whether his model is John McEnroe or an earlier, lesser-known Spanish star, Manuel Santana, whom he would have seen winning Wimbledon.

Cone, one could say, was ready and then some. His coup, which he pitched at the Stadium on July 18, 1999, is only the sixteenth perfect game in a century of major-league ball, but was also his own first no-hitter of any description. On three occasions in his fourteen-year career in the majors, he had carried a no-hitter into the eighth inning, only to be foiled. He remembers those scenes, tooin particular a wrong-field dribbler cued toward third with one out in the eighth by a Houston batter named DiStefano in 1992, when Cone was pitching for the Mets; the ball died just in front of Dave Magadan's frantic late charge from third. A Mets teammate of Cone's, the great reliever John Franco, thinks back to that injusticeand to DiStefano's lifetime .228 batting recordevery time Cone's name comes up in conversation. I was even in school with the guy, he says disgustedly. Benny DiStefano, behind me at Lafayette High in Brooklyn, and he kills Coney that way. He could be talking about Lee Harvey Oswald. The real enemy herefor Franco and every pitcheris luck, which stalks the field in every low-scoring game, guiding this rocketed line drive into the third baseman's mitt or nudging that bloop into an unreachable few inches of terrain, but which perversely must be given a secret save in every no-hitter.

The ache of the ancient DiStefano wound comes also from Franco's admiration for Cone's heart and stuff. He's a Picasso out there, he once said to me. Now John can wipe the crime from his recollection. Hearing about Cone's perfect game down in Baltimore, where the Mets are playing the Baltimore Orioles, he asks team public-relations director Jay Horwitz to have a bottle of Dom Perignon rushed to his friend.

Another pal and former pitching teammate, David Wells, who had thrown a perfect game for the Yankees at the Stadium a bit more than a year beforehis and Larsen's, which came in the World Series of 1956, are the Yankees' only previous perfectosgets the news at the SkyDome in Toronto, where he watches the final outs on the tube and manages to reach Cone by telephone in the Yankee clubhouse. Traded away to the Blue Jays over the winter, the Boomer is as happy about the feat as anyone in New York. My goose bumps are bigger than yours, he says to Cone. Welcome to the club. He promises to fly down that night, to celebrate with David. Maybe they'll drink Franco's champagne.

No-hitters are spare by nature because of what doesn't happen, and a perfect game almost Puritan, so the sense of release and jubilation over Cone's accomplishment extended everywhere in baseball that day. Waking up the next morning, I pictured how it would be talked about in the clubhouses around the leagues, with Cone's fellow-professionals arriving for work and telling each other how he had looked on the late news, down on his knees that way, and then turning his face toward the fans. Baseball's ceaselessly woven network of circumstances and conditions can be stopped at a moment's notice, frozen, as it were, and turned into lorewhere the ball came down, what the count was, what the weather was, what the standings were, who was in the on-deck circle, where we were sitting in the stands, or how we got the news watching at home. I have been following the game for more than seventy years and writing about it for almost forty, and I have my own little store of where and when. Mention Bobby Thomson's homer in 1951, Bucky Dent's deadly little flyer into the screen at the shadow-struck Fenway Park in 1978, or how New York soundedthat vast murmur across the parks and streetsat the moment when the Mets beat the Astros, down in Houston, after sixteen innings, to win the league championship in 1986, and I'll tell you how I felt at the instant, who was near me, and how we hugged or groaned or yelled. Cone's game fits in here nicely, with the kick this time coming not from significancethe game meant nothing in the standings to either team just thenbut from what I already knew about him as a pitcher and a man on that broiling Sunday.

There is also the matter of perfection, which baseball offers as a possibility in every game but at such odds that it's never mentioned. It doesn't cross your mind if you're a fan or a writer pencilling the lineups into your scorecard, even though those empty white boxes on the page sometimes whisper about an elusive little clarity that might lie out there beyond the accumulation of pitches and outs, grounders and base runners that will tell a game's story when it's done. Could bebut the thought flies out of your head because it's so crazy. Nothing went through my mind until the seventh inning, Yogi Berra said this time, afterward. Not another Yogi gem but close enough, and, as always, you knew what he meant.

Nothing was going through my mind that Sunday except the weather. I didn't have tickets, but the idea of seeing Yogi backit was going to be his Day at Yankee Stadium, with plaques and platitudes celebrating the official termination of a fourteen-year falling-out between the great Yankee catcher and his bygone boss, George Steinbrennerhad once tempted me. But forget baseball, I decided, it's too hot. This would be another beast of a day, the third or fourth in a row with the temperature in the upper nineties and the humidity nearing a hundred per centthe same sweaty blanketing we'd gone through in New York for a week at the beginning of the month, when there had been power blackouts and more news stories and sombre television panels about global warming. Now another dark cloud had come down. Two days before, the small plane in which young John F. Kennedy Jr., and his wife, Carolyn Bessette Kennedy, and her sister were flying to Martha's Vineyard had disappeared into the night waters near Gay Head, and this morning's