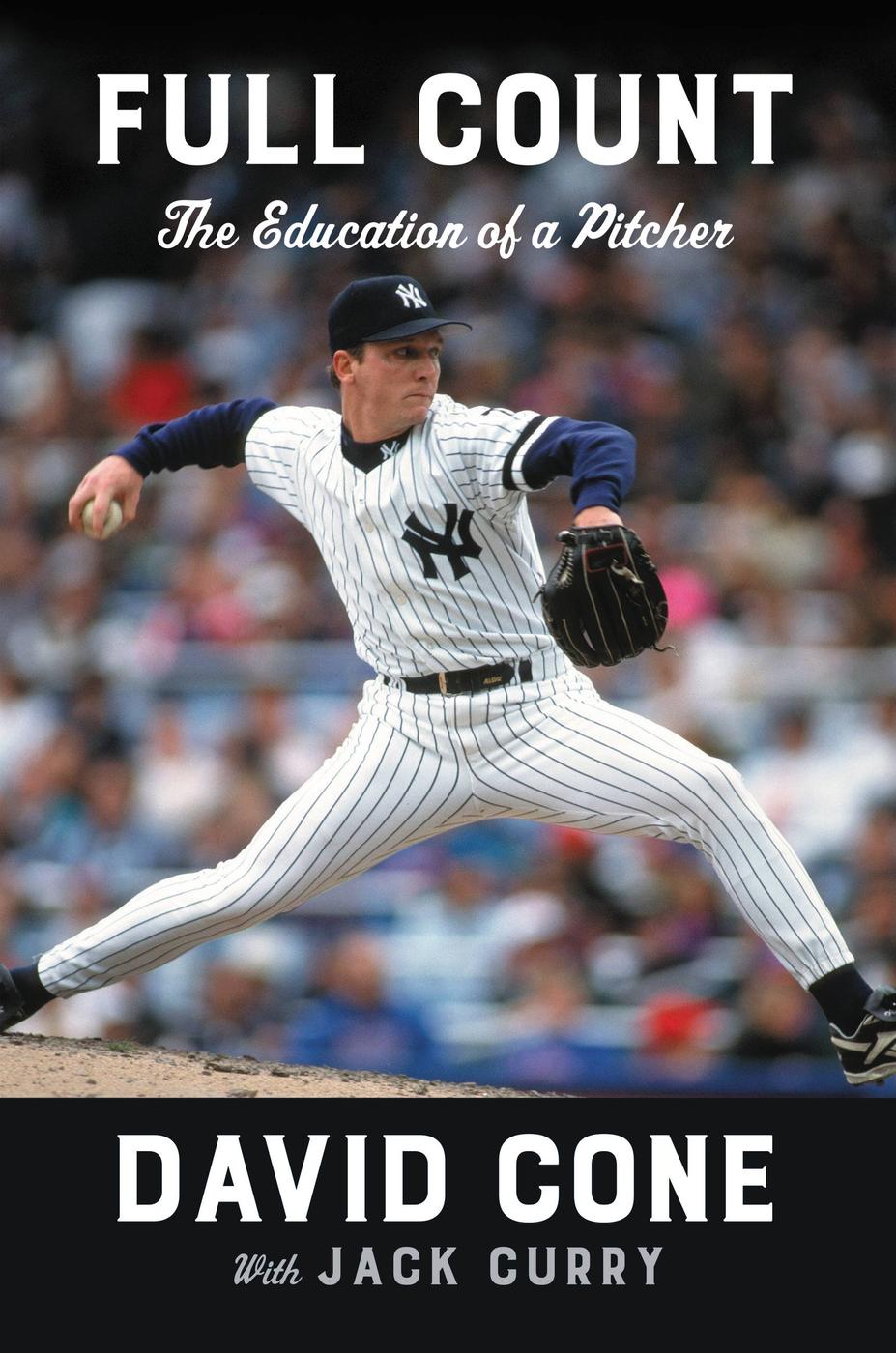

Copyright 2019 by David Cone and Jack Curry

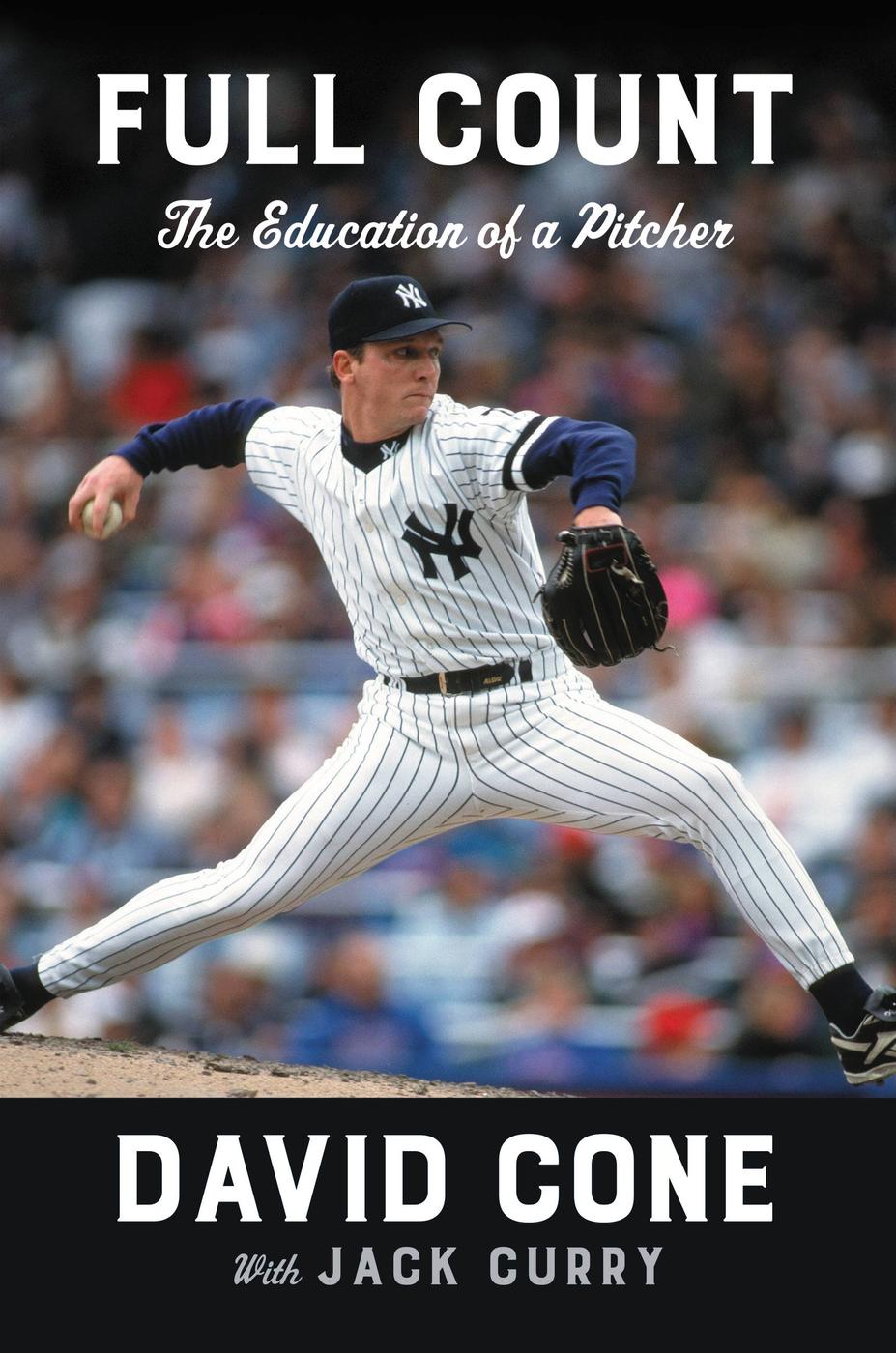

Cover design by Flag. Cover photograph by Focus on Sport/Getty Images. Cover copyright 2019 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Grand Central Publishing

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

grandcentralpublishing.com

twitter.com/grandcentralpub

Originally published in hardcover and ebook by Twelve in May 2019.

First Trade Edition: May 2020

Grand Central Publishing is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Grand Central Publishing name and logo is a trademark of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019930191

ISBNs: 978-1-5387-4883-1 (trade pbk.), 978-1-5387-4882-4 (ebook)

E3-20200117-DA-PC-REW

E3-20190308-DA-PC-ORI

For Mom, who understood about regression to the mean before it was popular.

For Dad, who was my first and best coach.

David Cone

For Mom, who will forever be my guiding light.

For Pamela, who is always my brightest light.

Jack Curry

Explore book giveaways, sneak peeks, deals, and more.

Tap here to learn more.

S TARING INTO THE BATHROOM MIRROR , I saw a sweaty-faced and steely-eyed man who was wondering how the next few minutes of his life would unfold. He looked serious and he looked concerned. I kept staring at the man, studying every inch of that weary face and those focused eyes, and I wondered if the man was powerful enough to pitch one more spotless inning. Please, I thought, just get three more outs.

Obviously, I was that man, the man who placed both hands on the sink, leaned forward, and pushed his nose within six inches of the mirror. I wanted some answers, and I needed some reassurance inside the Yankee Stadium clubhouse bathroom. After tossing eight perfect innings against the Montreal Expos on July 18, 1999, I changed into a fresh undershirt by my locker and retreated to the bathroom. I was alone, all alone, before the ninth inning and I gave myself a specific command: Dont blow this.

Of all the inspiring words that I could have used, my first words were Dont blow this. I challenged myself because I knew what motivated me, and I knew I responded well to being challenged. As an aspiring nine-year-old pitcher, I received tough love from my father, who was my first coach, so I used the same technique on myself. I let my forceful words sink in, the staring contest continued, and I added, Dont you dare blow this.

I wanted the reflection to talk back. I really wanted the man in the mirror to tell me he could do this and tell me everything would be all right. Taking inventory of how I had retired the first twenty-four batters, I knew my slider had been floating like a Frisbee, I knew my fastball was nicking the corners, and I knew the Expos seemed helpless as they swung early and often. Based on that mounting evidence, I finally told myself, You can do this. You have to do this.

Did I believe I could get the final three outs? Well, part of me believed it. Every pitcher has that mental tug-of-war with himself in almost every game. It doesnt have to be a potential perfect game for pitchers to wonder if theyre about to get a strikeout with a nasty slider or if theyre about to allow a homer on a hanging slider. For pitchers, the questions are never ending.

Throughout my career, I asked myself questions about the way I gripped my pitches, about the spin and velocity on my pitches, about the arm angles I used to deliver pitches, and about the smartest strategies for attacking hitters. Those questions and hundreds of others hover over pitchers, steady reminders about what we should or shouldnt do. I have lots of answers to these pitching questions and I have lots of pitching stories. All of these theories and opinions and tales will be unveiled in this book, an array of ideas from me and from others, a detailed assessment on the art of pitching and my life as a pitcher. I always believed pitchers need to be searchers, mound investigators who determine the best pitch to throw and the best way to throw it. Then do that again and again.

On that day in the stadium bathroom, I took deep breaths as the conversation between the dueling sides of my personality continued. The confident Cone was poised for perfection and envisioned it happening, while doubting David questioned whether it would ever happen. Even if a pitcher has the biggest ego in the world, hes going to experience doubts in pressure-filled situations. Back in 1999, I was trying to do something only fifteen other pitchers in major league history had ever done. I would have been delusional if I didnt have a doubt or two.

I was in my fourteenth major league season and, through all my creativity and quirkiness, I had never stopped and studied myself in the mirror during a game. And I never did it again. But this game was a special situation, a time where I was mature enough to pause, slow my brain and my pulse down, and absorb what was happening. As a thirty-six-year-old, I might never get another chance to pitch a perfect game, and I wanted to prepare myself in the best way possible.

Part of preparing myself meant preparing myself for failure, too. Pitching is a job that involves a lot of failure; even the greatest of pitchers throw balls about 40 percent of the time. So my frenetic mind told me that something could go wrong. There could be a bloop single or a ball that rolled sixty feet for a hit or one of my fielders could make an error or I could walk a batter. If any of those things happened, I needed to be OK with that result. Would I be OK if I ended up being less than perfect?

Forget that, I said. No, I wont be OK with that. Thankfully, the aggressive and confident me fought the equally aggressive and doubting me and told me to stay calm and keep pitching the same way. Dont even think about those bleak scenarios, I told myself in a conversation that felt like a devil-versus-angel chat. I guess I was the angel and the devil.

My internal struggle continued inside the bathroom, a bathroom so quiet that I heard water draining through the pipes. The adjacent clubhouse was empty because my superstitious teammates didnt want to talk to a pitcher who was working on a perfect game. No problem there. I just spoke to myself. Knowing the ninth was fast approaching, I had one final question: What are you going to do now?

For two or three minutes, I stood by myself and evaluated the man who was pursuing perfection. The last time I glanced in the mirror, I saw someone who looked energized. Maybe I had been revived by my strange pep talk. I knew how I would attack the Expos, so the physical side of my game was ready, but the detour to the mirror was a way to enhance my mental approach.