MARGE PIERCY

Winner of the Arthur C. Clarke Award for Science Fiction American Library Association Notable Book Award National Endowment for the Arts Literature Award Carolyn Kizer Poetry Prize

Marge Piercy is the political novelist of our time. More: she is the conscience.

Marilyn French

Piercys writing is as passionate, lucid, insightful, and thoughtfully alive as ever.

Publishers Weekly

One of the most important poets of our time.

Philadelphia Inquirer

We would have to look to a French writer like Colette or to American writers of another generation, like May Sarton, to find anyone who writes as tenderly as Piercy about lifes redeeming pleasuressex, of course, but also the joys of good food, good conversation, and the reassuring little rituals like feeding the cats, watering the plants, weeding the garden.

Judith Paterson, Washington Post Book World

Marge Piercy is not just an author, shes a cultural touchstone. Few writers in modern memory have sustained her passion, and skill, for creating stories of consequence.

Boston Globe

As always, Piercy writes with high intelligence, love for the world, ethical passion and innate feminism.

Adrienne Rich

What Piercy has that Danielle Steel, for example, does not is an ability to capture lifes complex texture, to chart shifting relationships and evolving consciousness within the context of political and economic realities she delineates with mordant matter-of-factness.

Wendy Smith, Chicago Sun-Times

PM PRESS OUTSPOKEN AUTHORS SERIES

. The Left Left Behind

Terry Bisson

. The Lucky Strike

Kim Stanley Robinson

. The Underbelly

Gary Phillips

. Mammoths of the Great Plains

Eleanor Arnason

. Modem Times 2.0

Michael Moorcock

. The Wild Girls

Ursula Le Guin

. Surfing the Gnarl

Rudy Rucker

. The Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow

Cory Doctorow

. Report from Planet Midnight

Nalo Hopkinson

. The Human Front

Ken MacLeod

. New Taboos

John Shirley

. The Science of Herself

Karen Joy Fowler

13. Raising Hell

Norman Spinrad

. Patty Hearst & The Twinkie Murders: A Tale of Two Trials

Paul Krassner

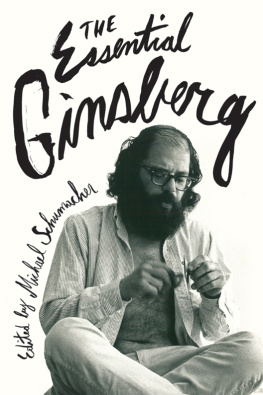

. My Life, My Body

Marge Piercy

A Dissatisfaction without a Name. Click: Becoming Feminists, edited by Lynn Crosbie. Toronto: Macfarlane, Walter & Ross Publishers, 1997.

The More We See the Less We Know. Los Angeles Times, March 24, 2004.

What they call acts of god. Monthly Review 65, no. 1, May 2013.

Statement on Censorship for the Pennsylvania Review. Pennsylvania Review.

Fame, Fortune and Other Tawdry Illusions. Boston Review 6, no. 1, February 1982.

Housewives without Houses. Syndicated by the New York Times, August 1994.

The hows; there is no why was published online in the Red Beard Anthology, 2014.

Touched by Ginsberg at a (Relatively) Tender Age. Paterson Literary Review 35, January 2006.

Tabula Rasa with Boobs. All the Available Light: A Marilyn Monroe Reader, edited by Yona McDonough. New York: Touchstone Books, 2002.

Why Speculate on the Future? Envisioning the Future: Science Fiction and the Next Millennium, edited by Marleen S. Barr. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2003.

Behind the war on women. Narrative Northeast, January 2014.

Never Catch a Break. Michigan Quarterly Review 27, no. 1, Winter 1988; and in Subversions: Anarchist Short Stories, vol. 2, foreword by Marge Piercy. Montreal: Anarchist Writers Bloc, 2012.

The Port Huron Conference Statement was delivered at a conference in Ann Arbor in 2012 called A New Insurgency: The Port Huron Statement in Its Time and Ours, 50th Anniversary.

Who has little, let them have less. Monthly Review 65, no. 8, January 2014.

Original to this volume: Headline: Lawmaker destroys shopping carts, Gentrification and Its Discontents, Nice words for ugly acts, and My Life, My Body. All Copyright Marge Piercy, 2015

My Life, My Body, Marge Piercy 2015

This edition 2015 PM Press

Series editor: Terry Bisson

ISBN: 9781629631059

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015930892

Outsides: John Yates/Stealworks.com Insides: Jonathan Rowland

PM Press P.O. Box 23912 Oakland, CA 94623

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed in the USA by the Employee Owners of Thomson-Shore in Dexter, Michigan www.thomsonshore.com

CONTENTS

A DISSATISFACTION WITHOUT A NAME

W HEN DID I FIRST become a feminist? I suspect it was around puberty, when I began to think hard about what I saw in my family and around me.

My mother had been sent to work as a chambermaid when she was still in the tenth grade, because her family was large and poor and needed the income she could bring in. She had an active mind, a strong sense of politics and an immense curiosity. She read a great deal, haphazardly. She had no framework of knowledge of history or economics or science in which to fit what she read or what she experienced, so that intelligent observations jostled superstitions and folk beliefs. She was a mental magpie, gathering up and carrying off to mull over anything that attracted her attention, anything that glittered out of the ordinary boredom of being a housewife. There was, truly, something birdlike about her, a tiny woman (only four feet ten) with glossy black hair who would cock her head to the side and stare with bright dark eyes.

She had grown up in a radical Jewish family where politics was discussed and debated. She had a sense of class conflict and social reality that was the most consistent and logical part of her mind. My father could easily be seduced by racism, sexism, Republican promises of lowering taxes. Like many working class men of his time, he started out on the left and moved steadily toward the right. My mother never wavered in her analysis of who was on her side and who was not. She trusted few politicians, but she appreciated those she thought fought for the rights of ordinary people.

My father very much enjoyed sexist jokes and told them till the end of his life, ignoring my attitudes if I was present. They were a way of knocking on the wooden reality of how things were with men and women and showing how sound it was. My mother did not tell such jokes and seldom laughed at them. However, she had attitudes of her own. She admired women who fought for other women, but she also had contempt for women. She complained of womens weakness, at the same time that she herself had few strengths to fall back on. She viewed sex as a powerful force that carried off women into servitude. A womans sexuality was a tremendous force that exacted a lifelong price from her.

When I was little, I thought of my mother as very strongfor certainly she had power over me. My father would punish me severely, with fists and feet and a wooden yardstick. But my mother was usually the one who set the rules, since my father did not take much interest, except sometimes to decide I must do something I didnt want to do, because he had contempt for cowards: climb a ladder to the roof, cross a narrow high footbridge. These demands had little to do with me, but were part of a war between them. She had many fears (he was driving too fast, too dangerously) that in some way pleased him. Her fear proved he was strong and able, in comparison to my mother (whom he never taught to drive). But I was the battleground in which he demonstrated how women were afraid by demanding I do things I feared.

Next page