Table of Contents

Guide

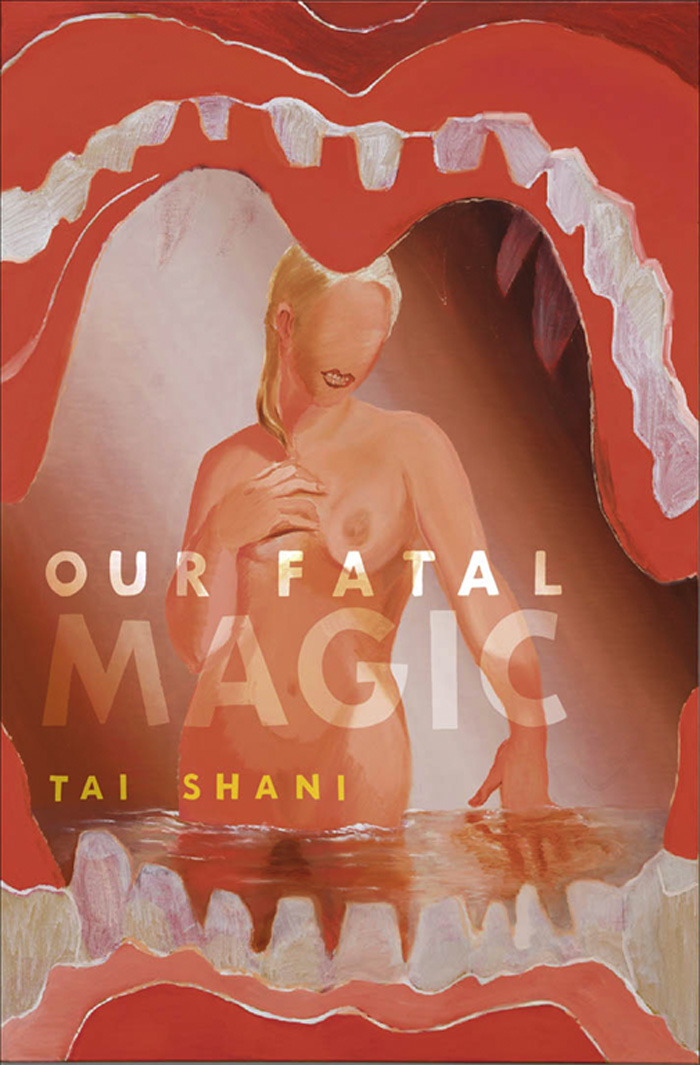

OUR FATAL MAGIC

Our Fatal Magic by Tai Shani

First published by Strange Attractor Press, 2019

ISBN: 9781907222818

Introduction Bridget Crone 2019

Cover illustration Heaty by Allison Katz

Our Fatal Magic typography by Eleanor Edwards

Layout by Jamie Sutcliffe

Published with assistance from the Royal College of Art

Tai Shani has asserted their moral right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the written permission of the publishers. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Strange Attractor Press

BM SAP, London,

WC1N 3XX, UK

www.strangeattractor.co.uk

Distributed by The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

And London, England

Printed and bound in the UK by TJ International

d_r0

Our Fatal Magic

TAI SHANI

Collected Texts from DC: Semiramis

Note

Our Fatal Magic is a collection of fragmentary fictions that were presented as monologues during the project DC: Semiramis, an expanded adaptation of Christine de Pizan's 1405 proto-feminist text, The Book of the City of Ladies. It took place over four years and was iterated through interconnected yet stand-alone performances, installations and films of monologue texts which represented the various characters in the adaptation. In 2018, DC: Semiramis culminated in a large-scale, sculptural, immersive installation that also functioned as a site for a twelve-part performance series, presented over four days. Each episode focused on one of the characters from an allegorical post-patriarchal city.

Elements of this collection have previously appeared in:

Buried

The Bodies That Remain, Punctum Press

On Violence, Ma Bibliotheque

Self Love, Eros Journal, Eros Press

The Happy Hypocrite, Book Works

Introduction

Wounds of Un-Becoming

Bridget Crone

DC: Semiramis is therefore a space-time that is both mythical and historical, a world built by and for women that is defined by their confinement and perceived threat. It is also the city that Pizan builds, the city for which she names the first stone Semiramis. (City of Women: Book II)

Here the feminine describes a mode of inhabiting the world, and the way in which a world acts to shape a body. And so, we might ask which bodies inhabit the world of DC: Semiramis? On what basis through which acts of coding or encoding are these bodies materialised? For in the world of DC: Semiramis, it is violence that possesses this formative power of constitution and inclusion. What does it mean to belong, and thus to delineate and collectivise experience in this way? This collective organisation of bodies is exemplified by the walls that surround Pizan's The City of Women, and likewise by the delineation of the space of the stage in the performance version of Shani's DC: Semiramis. The city and the stage each act as a border that differentiates between the inside and outside. It thus organises inhabitants, actors and citizens inside its bounds and excludes those outside. The bodies that materialise in the world of DC: Semiramis, bound by the city of women, are diverse and self-defined trans*, differently abled, of different ages, sizes and shapes. At the same time (and complicating things further), while the texts that make up Our Fatal Magic deal with questions concerning the formation of the body through violence, the work also addresses the violent dismantling of this very same body. Predominant then are not only the processes of becoming but also those of un-becoming; un-becoming as both an unravelling of the body-subject and an extension beyond it towards some other state of being or not-being. This is a battle which Shani elicits, of being or becoming a body, and at the same time escaping its confinement towards some other freer, more ecstatic state.

Evoking Pizan's pre-Enlightenment, proto-feminist text, The City of Women as an inspiration for DC: Semiramis has the effect of conjoining the struggle for the self-constitution, value and recognition of women's power (Pizan uses the term ability) with more contemporary questions concerning the very constitution of the human. It is the presence of Pizan's text in relation to DC: Semiramis (and its ritualised violence) that opens up a sense of the almost barbaric fragility or precarity of the feminine. For while there is a valorisation of a women's voice (knowledges, language and so on) and a demonstration of feminine skills and virtues in Pizan's text, this femininity is something that must be called forth against a backdrop of funerals, tournaments, violent seductions, abandonment and so on. Therefore, it is at once fixed through an expression of rigid gender roles and social conventions and, at the same time, fragile and subject to threat as the result of these very same boundaries. In Shani's work, this violence is present as both the violent struggle to have voice (recognition, representation) and the violence that threatens voice and ultimately self-constitution. Violence thus appears as both a forming and formative force that shapes the body, albeit precariously at times, while at others this violence is seized upon in defiance; it is possessed and inflicted by the feminine as self-authoring, as pleasure and as self-pleasuring. In this way, violence acts to shape the body in DC: Semiramis shaping it materially suggesting the body as a malleable form that can be thus transformed.

Shani's concern is therefore not only with the emergence of a kind of proto-feminism within Pizan's fifteenth-century context, but also with the question of what constitutes the body now. How might a body be organised in relation to other bodies? And, finally, how might we escape its confines (once established)? Translated more abstractly, this is firstly the question of what it is to have or be a body and what this might mean materially that is, what form a body might take. Secondly, it is the question of how this body is then organised or represented in relation to other bodies. Another simpler way of expressing this question of organisation and delineation is to simply ask: what constitutes the feminine? It is this question that demands a broader address and queering to approach gender beyond the binarism of Pizan and some of the other works of feminist science fiction (for example Sargeant) to which Shani refers, in order to expand the bounds of the feminine. The suggestion here is to think from DC: Semiramis towards a messier and more agonistic model of gender that moves beyond the binarism of Pizan (where woman is an existing category that battles to be recognised) or the neutrality of Piercy (where gender binarism is neatly managed and politely interchangeable). And finally, once this body emerges (complicatedly feminine, as noted earlier) in and through the world, we approach the third question: what are the possibilities for escape from the confinement of this body, both materially and psychically? That is to say, in asking what is being, we must also be prepared to entertain the question of what is not-being.

Yet in the texts that make up DC: Semiramis,