Contents

Guide

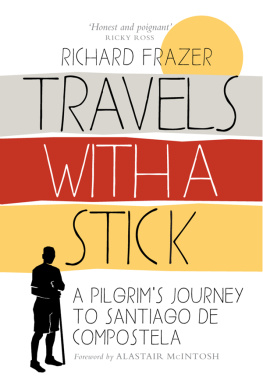

For Kate, Will, Jay and Tom joyful companions

First published in 2019 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

Copyright Richard Frazer 2019

Foreword copyright Alastair McIntosh, 2019

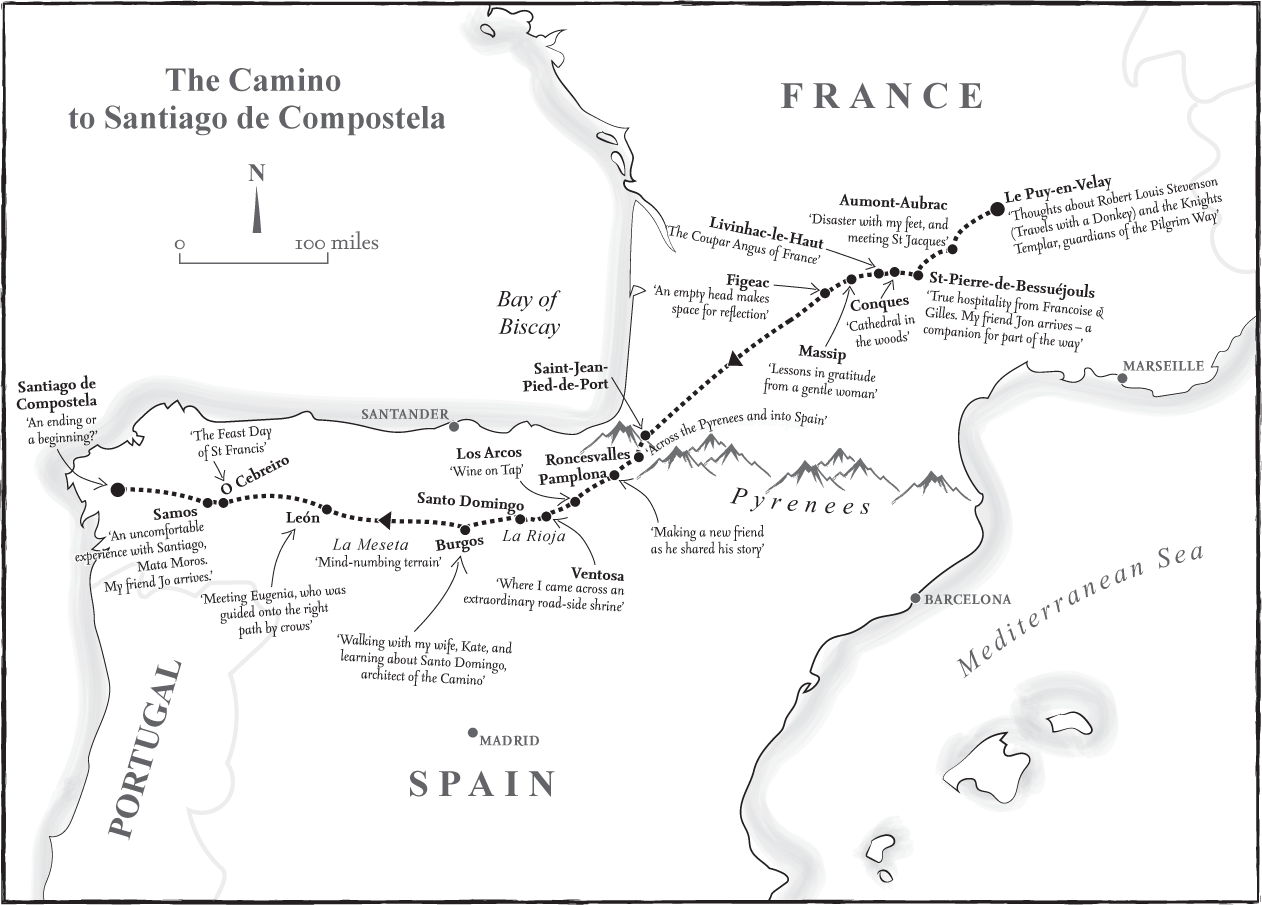

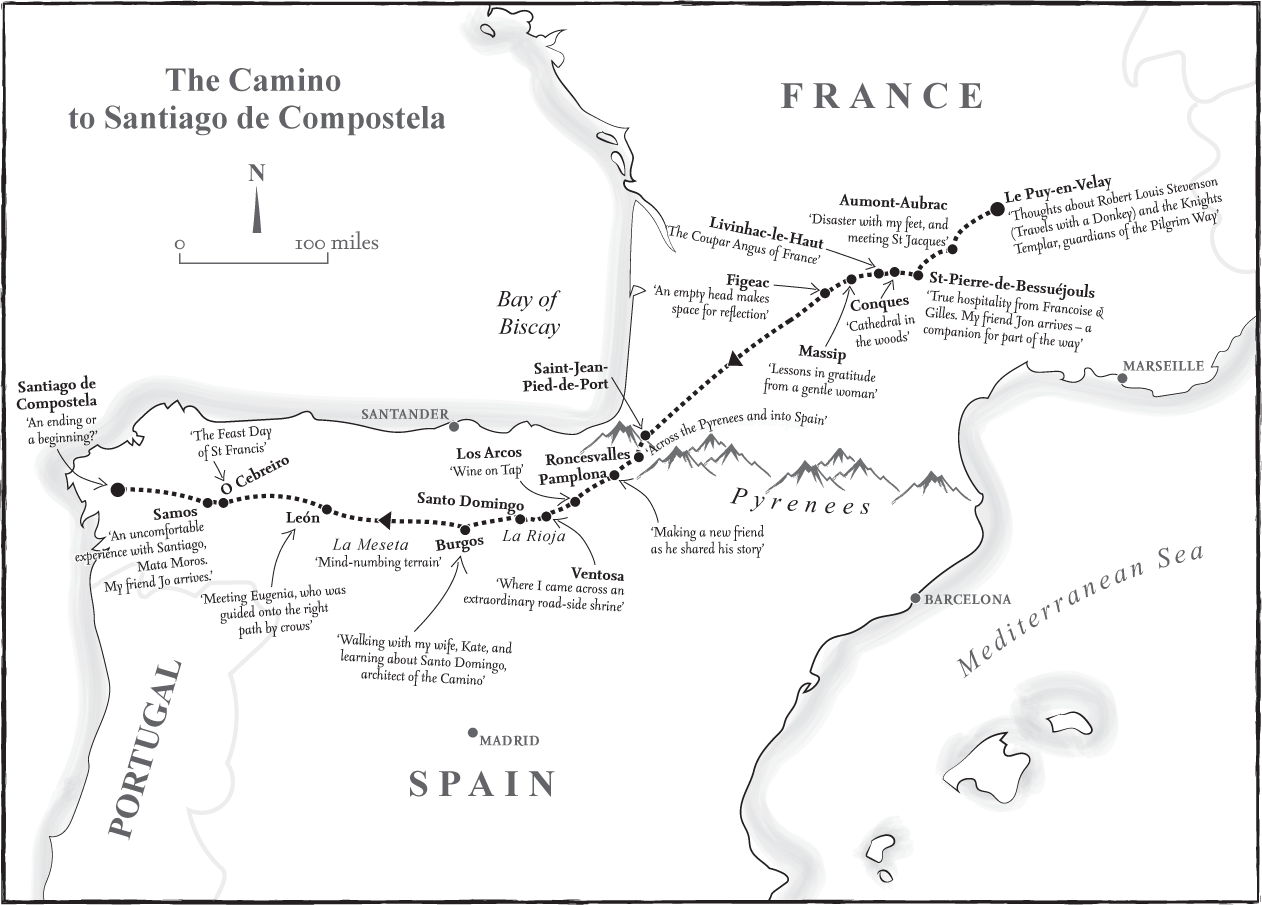

Map drawn by Pixo Creative Services

ISBN 978 178027 568 0

The right of Richard Frazer to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Designed by James Hutcheson

Typeset by Initial Typesetting Services, Edinburgh

Printed and bound by Gutenberg Press, Malta

CONTENTS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

St Jacques in the cathedral of Le Puy-en-Velay

Descending into Monistrol-dAllier

Dinner in Le Domaine du Sauvage

Estaing

With the stick in Conques

Heading out of Conques

Jon and me

Roncesvalles

Looking towards La Rioja

Puente la Reina

Shadows of evening after a long day on the way to Los Arcos

The king and queen ready to bop at Cirauqui

Wine on tap

Free dinner at Villa Franca

A cruciero

Myron and Jacques take a breather

Ancient Roman road

The cathedral of Burgos

With Santo Domingo

Jo and me taking in the aroma of Galicia

Proof that the starting point of the Camino, like any pilgrimage, is wherever you want it to be

The Benedictine monastery at Samos

Journeys end: at Santiago de Compostela

My completed pilgrim passport

FOREWORD

Few people can claim to have changed the course of history with respect to pilgrimage, but in a small way, as I shall share shortly, Richard Frazer is one of them. But first, early in this book, he remarks that no one does the Camino. Rather, this ancient pilgrimage route through France and Spain to Santiago does you.

With crisp narrative flow, were led through nearly 700 miles some 1,000 kilometres of countryside and villages in daily walks and nightly stops at hostels, inns and monasteries. Its not just Richards running up against his own physical limitations thats challenging. Its also the encounters with fellow travellers on the way. The ones who snore like weaving looms all night in dormitories. The ones who humble him with kindness, as if hed met the patron saint along the route.

Richard loves observing human nature. In one scene, the conversation amongst strangers round the dinner table gets dominated by a pilgrim from Geneva. His commandeering questions draw the motley walkers into the practicalities of kit and boasts of daily mileage tallies. Everyone gets caught up by the competitive pull of his invasive mental field, until he throws his questions to a quiet and unassuming French lady. Why was she amongst them, round the table? Was it for spiritual reasons, or was she just an avid walker? She was there, she answered quietly, to give thanks. Her answer served both as a soft rebuke and penetrating gift not only to the brusque Genevan, but to them all.

Such are the anecdotes that interlace this book. There is a deeper stratum too. As he walks, Richard tries as best he can to avoid being found out that hes a clergyman. So much of the church, he says, has become an embarrassment. The institution trots trite dogmas out and gives unsatisfying answers to deep questions. Mostly it forgets its own complicity in violence, going back to Roman times and all those later holy wars. Here we encounter Richard as the Presbyterian minister. A Protestant in the spirit, as the name implies, the spirit of protest. A senior office-bearer in the Church of Scotland, standing in the shoes of militant Reformation theologians yet one who sees the need within his own denomination to face up to and redress the cold, heartless impact of a Calvinism that has too often been used to intimidate people.

Its not, he insists, that people arent spiritual any more. Its more that bombast from Geneva whether left over from the sixteenth century, or from an overbearing fellow pilgrim round the dinner table no longer speaks to a younger generation that, with good reason, is sensitised to anything authoritarian. Today, it is in the recovery of spirituality, not religiosity, in which most seekers yearning lies. There lies freedom of the soul, or as Richard puts it: To be a pilgrim you dont have to jump through hoops or sign up to doctrines youd rather question you just have to set off!

He should know, indeed, the institution itself is waking up. Within the Church of Scotland as by law established, Richard convenes the influential Church and Society Council, the committee charged with questions of faith and nationhood. This is where our intrepid walkers small but significant contribution to pilgrim history kicks in. He doesnt admit to it in this book, but in 2017, under his watch and with his theological input and encouragement, the churchs General Assembly reversed its getting-on 500 years hostility to pilgrimage. As its own theologians say, the Reformed church is always reforming itself, and here we saw that happening.

But what had been the original Protestant objection to pilgrimage? Not without some reason in their time, Reformation clergy such as Luther and Calvin held that pilgrimages commercialised religion. They kept the people off their work. Pilgrim shrines were funnels that channelled money away from local needs and back to Rome. Luther was the one who really laid it on. In 1520 in a grandiloquent address to the Christian nobility of Germany he had described pilgrimages as giving occasion for countless causes of sin. Such peregrination around the countryside was to be done away with except, he conceded, when it was out of curiosity, to see cities and countries. In other words, the peasants were to quit their holidays, but the nobility could keep their tourism. You could gallivant off to wherever you could afford, provided it was devoid of religious intent. That was for keeping firmly beneath the thumb of Luthers pulpit.

It has been this use of religion for psychological and political control that, as Richard diagnoses it, has closed the doors on faith for many. Far from being a trellis, a structure that leads the vine of spiritual life towards the light to ripen grapes and make good wine, organised religion has struggled to give life to many in our times. The vine has had to find its own wild way. Thats where pilgrimage comes into play. As Richard told the