HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

FIRST EDITION

Daniel Storey 2019

Cover layout design HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

Cover photographs Action Images/Reuters

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Daniel Storey asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

www.harpercollins.co.uk/green

Source ISBN: 9780008320492

Ebook Edition January 2019 ISBN: 9780008320508

Version: 2018-12-10

CONTENTS

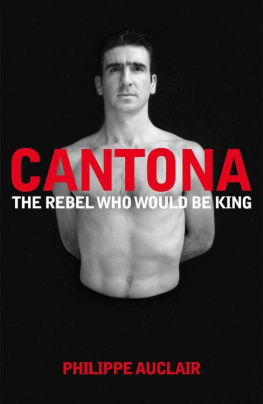

Are you big enough for me?

Eric Cantona was not the first foreign footballer in England, but he might well have been the most influential. No single player better represents English footballs rapid transformation from the working-class, kick-and-rush game of Division One a sport that had largely remained the same for half a century to the glamour and exoticism of the current Premier League.

Before the mid-1990s foreign players were a luxury item, mysterious circus animals tasked with performing for our entertainment. At that time, foreign had a pejorative connotation: fancy, flash, weak-willed. Foreign imports could temporarily call England home, but it would never be their natural habitat. They would hate our weather, hate our food, hate the physicality of the game that we invented and then gave to the world. And they would soon leave for whence they had come.

That was odd, given the success of some memorable foreign imports in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Ossie Ardiles and Ricky Villa at Tottenham, Arnold Mhren and Frans Thijssen at Ipswich, Johnny Metgod at Nottingham Forest; all became fan favourites due to their natural talent and willingness to embrace the culture of their clubs. But their success did not provoke an immediate wave of immigration.

The first weekend of the inaugural Premier League in August 1992 demonstrated English footballs insular nature. The 22 clubs handed appearances to only 13 non-British players. Four of those were goalkeepers and another four (John Jensen, Michel Vonk, Gunnar Halle and Roland Nilsson) were defensively minded players.

A high percentage of foreign players in the Premier Leagues early years were from northern European countries Denmark, Sweden, Norway, the Netherlands. They were preferred not only on account of their assumed comfort in dealing with the British climate, but also because they came from countries where English football was already a staple. One of the first questions asked by a club owner or manager when signing a foreign player was Can he fit into the English game?

Having supported and followed English football all my life, like every other Norwegian, it was a dream to play in England, former Swindon, Middlesbrough, Sheffield United and Bradford striker Jan ge Fjrtoft says. We had grown up with Match of the Day every Saturday night, you see.

Of the others, Andrei Kanchelskis and Anders Limpar were two who had skill as their primary characteristic, but the pair started only 26 league games between them for Manchester United and Arsenal in 1992/93. Ronny Rosenthal was a workmanlike Israeli striker for Liverpool who had become the most expensive non-British player to join an English club in 1990. Polish winger Robert Warzycha was the first player from mainland Europe to score a Premier League goal for Everton but managed only 18 starts in the competition before being sold to Hungarian side Pcsi MFC.

The Premier League was therefore desperate for a poster boy. Clubs had the means to pay higher wages thanks to a broadcasting deal with Sky Sports worth an initial 304 million. Many of the top-flight stadia had been improved following the recommendations of the Taylor Report. The stage had changed; the actors had not. In late 1992 the Premier League was nothing more than the old First Division rolled in glitter and studded with rhinestones.

Enter Eric Cantona and Manchester United. In November 1992, in strolled a Marseillais enigma whose confidence was only matched by the size of his reputation. With Leeds United keen to get rid of their tempestuous Gallic star, Alex Ferguson believed he had found the player around whom he could build the first age of his dynasty.

If ever there was one player, anywhere in the world, that was made for Manchester United, it was Cantona, as Ferguson would subsequently say. He swaggered in, stuck his chest out, raised his head and surveyed everything as though he were asking: Im Cantona. How big are you? Are you big enough for me?

More than any other player, it was Cantona who unlocked the door for the Premier Leagues foreign revolution. He proved that the skill European and South American players stereotypically possessed need not exclude the passion and will to win of the old English First Division. Just as Glenn Hoddle and Terry Butcher two fixtures of the England national team in the 1980s were as disparate in style as it is possible to conceive, so too could foreign players come from any part of the footballing spectrum. If that now sounds like an unnecessary truism, it was far from obvious in 1992.

But Cantona became more than a trailblazer; he was a cultural and sporting icon. No single player was more responsible for the boom in replica shirt sales and merchandising (official or otherwise), while the ubiquity of Cantonas face thanks to a sponsorship deal with Nike was new ground for English football. In a thousand playgrounds across the country, collars on school-uniform shirts were turned up as children mimicked the hallmark of their hero. For a few years every kid was Eric Cantona. If those children have now turned 30, many still harbour the same adoration.

Cantonas personality could never have been so influential without talent. He scored 82 times in 185 games for Manchester United, but it was his style of play that was so unusual. Before the Premier League era there was very little tactical fluidity in English football. Defenders defended and attackers attacked, and players typically stayed in formation.

Cantona preferred a different method. He started as a nominal strike partner usually to Mark Hughes or Andy Cole but dropped deep in between the lines of defence and midfield, dragging immobile central defenders out of their position and comfort zone. Cantonas technical expertise allowed him to link play effectively, and he became as renowned for his chance-creation as his finishing. Cantona is credited with 56 assists in 156 Premier League games. The only other strikers of his era to register more Cole, Alan Shearer and Teddy Sheringham all played at least 250 more matches.

Conversely, Cantonas talent could never have been so influential without personality. Cantona was a leader of Manchester United not just because of his talent, but through sheer strength of character. As Roy Keane so eloquently put it: Collar up, back straight, chest stuck out, he glided into the arena as if he owned the f***ing place. Any arena, but nowhere more effectively than Old Trafford. This was his stage. He loved it, the crowd loved him.

Cantonas unwavering self-belief it bordered on swaggering arrogance was not a natural trait, but a deliberate tool of his success. Ive said in the past that I could play single-handedly against eleven players and win, he wrote in