HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2018

FIRST EDITION

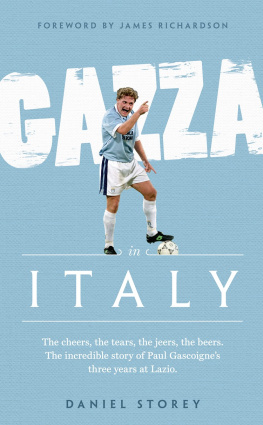

Daniel Storey 2018

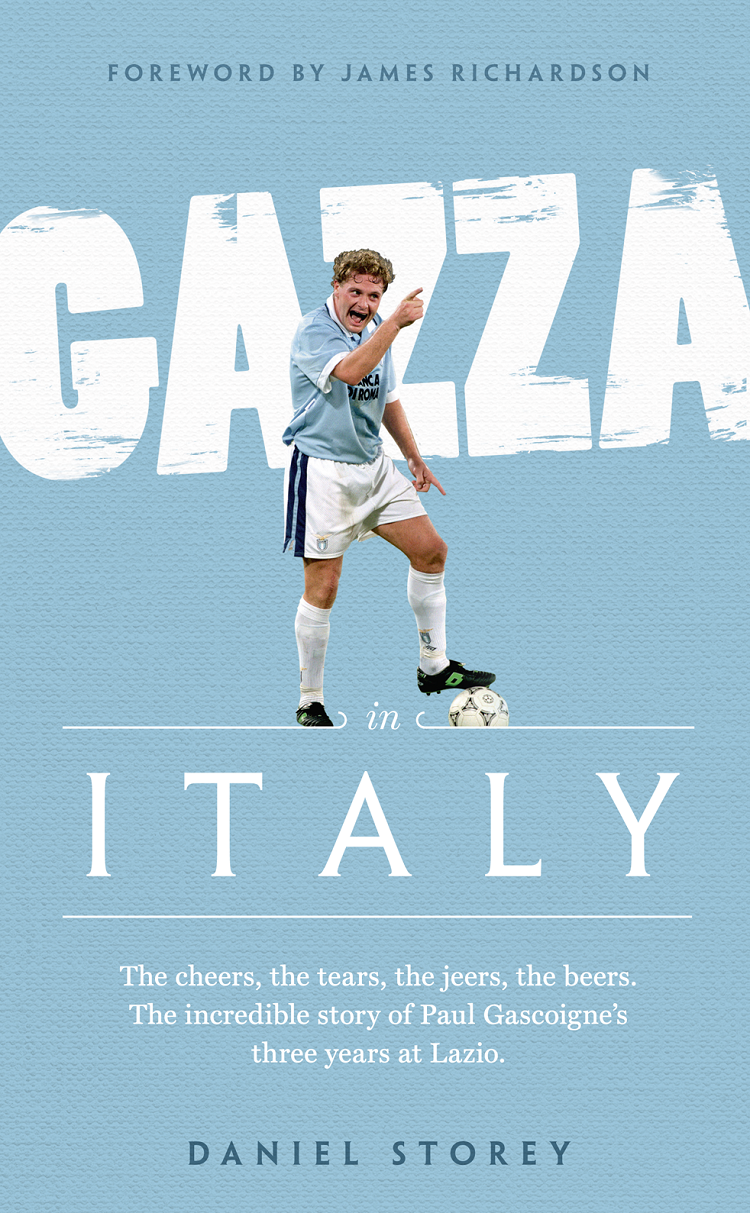

Cover layout design HarperCollinsPublishers 2018

Cover photograph Neal Simpson/EMPICS Sport/PA Images

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Daniel Storey asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at www.harpercollins.co.uk/green

Source ISBN 9780008300869

Ebook Edition June 2018 ISBN: 9780008300876

Version 2018-06-28

To Livvy,

whose patience with

football is stronger than

my obsession

Contents

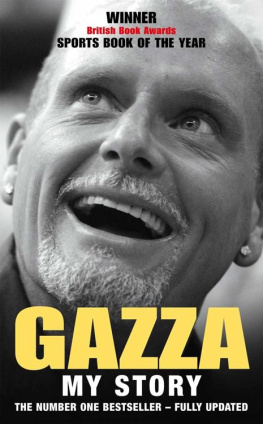

I first met Paul Gascoigne on the grassy slopes of the garden at the Hotel Cavalieri in Rome.

Its a magnificent spot the hotel overlooking the Eternal City across a series of leafy lawns and on that sweltering afternoon in August 1992 I was feeling the heat more than most as I prepared to meet the footballing phenomenon Id been hired to babysit and produce for Channel 4s Gazzetta Football Italia programme.

The task was daunting. Unlike me, Paul was famous, successful and very good at kicking a football, one of the chief life skills any right-thinking boy should aspire to. Worse still, he was almost exactly my age. Clearly, he would soon be making me cry and dispensing Chinese burns on a regular basis.

Instead, Paul surprised me by shaking my hand warmly, and giving me a look that I was often to see: wary, but also ever-eager for an audience. And so we began a polite friendship, one that lasted for precisely the amount of time that he was in Italy.

We were very different, but while he was there we had two things in common: our new life in the sweaty bustle of Rome, and our weekly commitment to filming his TV links and diary entry for Channel 4s Saturday-morning Italian round-up.

The filming went tits-up just a few weeks in, as Paul missed our appointment by a day or two. Timing was always an issue with him perhaps his own way of finding some freedom within the intense bubble in which he lived. It mattered little, though. Whenever he was with you, youd forgive him anything.

Paul was always generous and down to earth. He constantly seemed to want everyone around him to be happy as long as it didnt require his punctuality. Wed film his segments, and then, because the life of a footballer isnt actually that exciting a topic, wed try and improvise some theatrics to include in the show. This always brought out the best in Paul. Whether putting his entire head inside an Easter egg or waking up alongside me holding a kitchen whisk as a sex toy, he was game for anything for the camera and most things off it.

The years he spent in Italy were not without their ups and downs, and featured yet another serious leg injury this one in training, courtesy of a fresh-faced Lazio teenager called Alessandro Nesta. His time there was ended finally by the arrival of possibly the single worst manager Paul could ever encounter, Zdenk Zeman, whose rigorous tactics and utter commitment to player fitness were the antithesis of Gazzas own plastic-tits-out charm. Paul departed Rome for Glasgow soon after, leaving behind a feeling that although this city had loved him more than any other, it never really saw the best of him.

Perhaps. For that brief spell though, Paul gave Lazios fans so much to delight them. His goal in the Rome derby cemented his place in Laziali hearts and his mazy slalom against Pescara a place in club legend. Meanwhile, his irreverent style meant that uniquely this was a player loved by fans on both sides of the Tiber. Ubriacone, con lorecchino, vieni qua e facci un pompino, Romas fans would sing at the Stadio Olimpico, with words ill-suited to translation here, but when out with Paul in Rome they would be the first to run to salute him: Grande Gazza! Sei un mito!

Its a pleasure to look back now on the joy that period brought, when Gazza was just a supremely talented young man doing what he did best.

The thirty-one days between 8 June and 8 July 1990 were English footballs Enlightenment. Not only was this the first time an England team had reached the World Cup semi-final on foreign soil, when for a few precious days we truly did believe, but Italia 90 precipitated the birth of a new age for our national game.

From its previous position as a cultural outpost during the 1980s, English football was suddenly positioned at the forefront of social life. Books, television programmes and even theatrical productions with football as their central tenet were all successful. People began to consider football as an art form.

Italia 90 also marked the crossover between football as a working-class game and middle-class pursuit, with satellite television inaugurated and plans for the establishment of the Premier League for better or for worse in place. Out of the darkness and into the light (even if that light became too blinding for some).

For those four-and-a-half weeks, a global sporting event played out in glorious technicolour. The green of the grass felt greener, the white of Englands shirts seemed brighter than ever before. The television coverage presented Italy with a shimmer and sheen, as it were a month-long dream sequence.

We cried, laughed and sat spellbound as Tot Schillaci ran, Roger Milla danced, Frank Rijkaard spat, Bobby Robson jigged and Gazza cried. Twenty-five thousand hairs on the necks of 25 million people stood on end every time Nessun dorma was played, as if standing to be serenaded by Luciano Pavarottis majestic version of the aria. England fell to glorious failure, just as they had four years previously, but the emphasis this time was on the glory.

If our eyes were suddenly opened to the possibility of footballing multiculturalism, Italia 90 also re-sold the image of English football and the English football supporter. Papers released in 2012 revealed that the government, still led by Margaret Thatcher, had considered withdrawing the national team from the 1990 World Cup over concerns that it would become a natural focus for hooliganism.

Instead, the travelling hordes proved once and for all that if you treat people as adults, they are far more likely to behave like them. Transport, accommodation and match tickets were available at reasonable prices, a world away from the corporate homogeny that now envelopes each major tournament. There were impromptu kick abouts in town squares, and late-night parties to celebrate good results and forget bad ones. The tournament did not pass without trouble, but the behaviour of England supporters was appreciated by the Italians. A country had prepared for war; it got the odd skirmish.

As Pete Davies, author of the seminal All Played Out, told the Guardian in 2015: Prior to Italia 90, football in England was perceived as a squalid, hooligan-ridden, embarrassing sump of gormless violence. Our team was crap, our supporters were worse, and you did not talk about it over dinner.