CANTONA

PHILIPPE AUCLAIR

CANTONA

THE REBEL WHO WOULD BE KING

MACMILLAN

First published 2009 by Macmillan

First published in paperback 2009 by Macmillan

This electronic edition published 2009 by Macmillan

an imprint of Pan Macmillan Ltd

Pan Macmillan, 20 New Wharf Rd, London N1 9RR

Basingstoke and Oxford

Associated companies throughout the world

www.panmacmillan.com

ISBN 978-0-230-74702-9 in Adobe Reader format

ISBN 978-0-230-74701-2 in Adobe Digital Editions format

ISBN 978-0-230-74703-6 in Mobipocket format

Copyright Philippe Auclair 2009

The right of Philippe Auclair to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

You may not copy, store, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Visit www.panmacmillan.com to read more about all our books and to buy them. You will also find features, author interviews and news of any author events, and you can sign up for e-newsletters so that youre always first to hear about our new releases.

To Jean-Marie and Marion Lano

Contents

Foreword

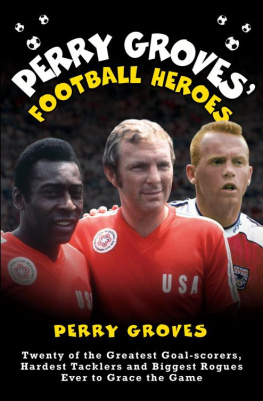

Les Caillols the village square.

The sign reads: No Ball Games.

Id originally thought of giving this book a different title: The Life and Death of a Footballer. This was not to satisfy a desire for gratuitous provocation. ric Cantona, the footballer, really died on 11 May 1997, when he swapped his Manchester United jersey with an opponent for the last time.

Throughout the three years that this book took to research and write, the idea that this death a word Cantona himself used liberally when speaking of his retirement was also a suicide became a conviction of mine. In January 1996, when he was at the height of his powers, he turned down the chance to rejoin the France team. He chose not to be part of an adventure that would lead to a World Cup title in 1998. Why and how you shall see for yourselves. At this stage, it should be enough to say that this apparently incomprehensible decision fitted in with the strange logic of his progress so far, an eccentric parabola the like of which French and English football had never seen before, and are unlikely to see again.

There have been many accounts of Cantonas life, perceived failings, failures and achievements over the years; too many of them published in the immediate wake of his prodigious success with Manchester United to stand the test of time. Some have focused on his troubled personality, and sought clues to his instability and tendency to explode into violence. Others were mere picture books or collections of match reports which could only satisfy the hungriest and most easily sated of fans. Some (particularly in France) were attempts to make a martyr of him, a victim of the establishment or of xenophobia. Others deplored the self-destructive undercurrent in his character, which had prevented him from becoming one of the games all-time greats.

One thing united these attempts at making sense of the man who transformed English football to a greater extent than any other player of the modern age: as I soon discovered, even the most thoughtful and penetrating of them were reluctant to question the mythical dimension of Cantona. To question not to deny, as so many of his deeds instantly became, literally, the stuff of legend.

ric himself helped build this legend. His sponsors exploited it with glee. It provided writers with tremendous copy. A strange balance was thus found: it was in nobodys interest to look beyond the accepted image of a prodigiously gifted maverick, a gipsy philosopher, a footballing artist who could be exalted or ridiculed according to ones inclination or agenda. Cantona attracted clichs even more readily than red cards.

Ill not claim to have unearthed a truth that had proved elusive to others; my ambition was to write this work as if its subject had been a sportsman (or a poet, or a politician) whod left us a long time ago. Which, in Cantonas case, is and isnt true. It is true because he scored his last goal in competition twelve years ago and because the ric who still exerts such fascination, the ric one wants to write and read about, ceased to exist when he last walked off the Old Trafford pitch. What followed his efforts to turn beach soccer into an established sport, which were remarkably successful, and his attempts to be accepted as a bona fide actor, which were largely ignored outside of France are part of another life, a life after death if you will, which I will only refer to when it has a relevance to what preceded it. It isnt true because his aura has not dimmed since he stopped kicking a football. Manchester United fans voted him their player of the century several years after hed retired, ahead of the fabled Best-Law-Charlton triumvirate. More recently, in 2008, a poll conducted in 185 countries by the Premierships sponsor Barclays found him to be this competitions all-time favourite player. That same year, Sport magazine chose the infamous Crystal Palace kung-fu kick as one of the 100 most important moments in the history of sport. Ken Loach has made him a central figure in his latest film, Looking for ric. The ghost of ric Cantona will haunt us for some time to come.

True, legends have a habit of growing as actual memories are eroded by time. But I didnt want to debunk this legend: those looking for scandalous titbits and innuendo will be disappointed, Im afraid. But I wished to interrogate the myth and chart rics steps from promise to damnation, then redemption and idolatry, with the exactness of a mapmaker. What I can promise is that there will be a few surprises along the way.

The first decision I took was an easy one for me, even though it intrigued several of my friends, and will puzzle a number of readers. I informed ric Cantona that I was writing a book about him, first by fax through a mutual acquaintance, doing it twice for good measure, then in person, on the occasion of one of his regular visits to England. I was told that he was aware of my project and that I could consider this an unspoken assent. I had confirmation of this when he thanked me for my undertaking during one of his visits to England, and that was that.

He had, after all, already put his name to an autobiography published shortly after hed won his first title with Manchester United in 1993, Un Rve trange et fou , which was so haphazard in its overall conception, and so inaccurate in its detail, that it clearly showed that the idea of going over the past made little sense for him. I was also wary that his entourage might try to exert a control over the finished work that I wouldnt be willing to accept. rics previous chroniclers have all encountered the same problem: their subject has been demonized to such an extent that those who love him feel a natural urge to protect him with a fervour bordering on fanaticism. To achieve what Id set out to do, I had to refuse to choose a camp, something which would have been impossible had Cantona himself been looking over my shoulder. In fact, hed have been holding my pen.