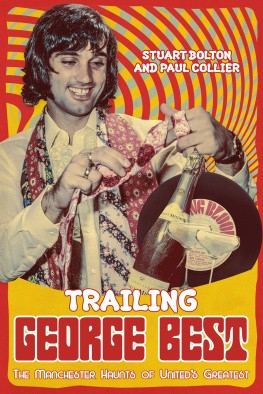

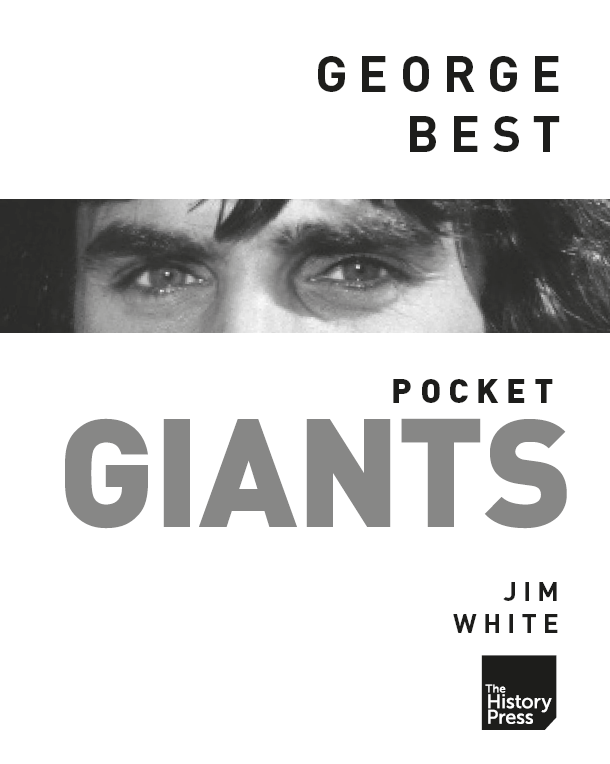

Why is George Best a pocket GIANT?

Because he rose to stardom from a humble background.

Because he brought the Swinging Sixties on to the football pitch.

Because he remained an idol after he had walked away from his career, and even after his death.

Because he is arguably the best British footballer of all time.

JIM WHITE is a journalist and broadcaster on a number of subjects, including sport. He has written for the Independent, the Guardian and latterly the Telegraph. He is a regular contributor to BBC Radio 5s Fighting Talk and BBC Radio 4s Saturday Review and is frequently heard on TalkSport.

Cover image: Colorsport / Rex / Shutterstock

First published in 2017

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2017

All rights reserved

Jim White, 2017

The right of Jim White to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

epub 978 0 7509 8205 4

Original typesetting by The History Press

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Introduction

When I die and they lay me to rest

Im going on the piss with Georgie Best

Chant sung to the tune of Norman Greenbaums Spirit in the Sky by Manchester United supporters during a Premier League match against Manchester City, Etihad Stadium, Manchester, Sunday 20 March 2016.

It was no more than half an hour after he had staggered out on to the stage that George Best called Bobby Charlton a cunt. We had gathered in a small theatre in Richmond upon Thames one evening in 1993 for an audience with the greatest footballer Britain has ever produced and this was not what anyone had paid to hear. Best was onstage with his former Fulham teammate Rodney Marsh and things had got more than a little ragged. The star turn (though Rodney would probably remember the billing differently) had arrived late, his progress delayed by a diversion via what appeared to be several bars.

Marsh was there first, forty minutes after the advertised start time, doing his best to fill. Resplendent in a glittery dinner jacket and soft blond mullet, on his feet he wore shiny, low-cut slip-ons that barely covered his white towelling socks.

Gout, the man next to me said, pointing at the footwear, as Marsh struggled to hold the audiences attention. Those are the shoes of a man with gout.

It was already shaping up into that kind of evening. But when Marsh was able eventually to pass on to the audience the news that the headline act was in the vicinity and summoned Best from the wings, there was a sizeable ovation. There may have been no more than 100 of the faithful gathered there to see the footballing giant speak, but the affection was obvious, mingled with relief that he had actually, finally, turned up. How we all wanted him to charm us, to tell us how it was, to throw in a few indiscretions, to be the Bestie of our imagination.

The visual signs, however, werent encouraging. This was the man whose physical attributes were once so arresting he would invariably leave any room accompanied by the most beautiful woman in it. Now he didnt look good. The collar of his dinner jacket was flecked with dandruff, his face was bloated, his skin flaky, greying stubble was sprouting untamed from all parts of his face and neck. He stumbled across the stage to his seat, swaying, emitting a Tourettes-like series of grunts and grumbles.

The frame of mind he was in as he took his seat was horribly familiar to those who knew him. A hugely intelligent man, when afflicted by this sort of mood he became overwhelmed by a nihilistic sense of purposelessness. It had stalked him all his adult life. A few drinks were all it took for the questions to start filling his head. Why was he here? What was he doing sitting on stage in a poxy regional theatre spinning yarns to a few dozen sycophants? What was the point? He looked like someone who wanted to be somewhere, please God, anywhere, other than where he was. Even from the back of the auditorium you could see the dismay clouding those once sparkling blue eyes.

It was billed as a question and answer session and it soon became clear the questions for which the audience sought answers were not going to trouble the judges of the Pulitzer Prize. Who was his toughest opponent? Who was the best player he had played with? What did he reckon to Paul Gascoigne, at the time the latest footballer to be dubbed the new George Best? And, talking of Gazza, if he were picking a first eleven of top footballing drinkers, who would be in it? Apart from himself, obviously.

This audience of men we were all males occupying the auditorium wanted to revel in the old days, the good times, those matches when we had gaped in wonder at Besties panache on a football field. All we needed was a line or two, thrown from the stage. Simple openings for a joke, these were easy questions to be soft-batted back whence they came with a smile. For a speaker mining the nostalgia circuit, it was the gentlest of audiences, the safest of open goals.

But Best was never one attracted by open goals. For him there was no challenge in easy. When he played football, if ever faced by an unguarded net, he would check back and mischievously find a defender to beat again, or the goalkeeper to taunt before slipping the ball past him. You can see it in the footage of the six goals he scored for Manchester United in an FA Cup tie against Northampton Town in the early spring of 1970. It remains a record individual goal tally in the competition, but he doesnt look happy about achieving it. As the count tots up, his shoulders sink, the celebrations become more muted. For his final goal, as he jinks his way round the goalkeeper, for a moment he stalls, stops on the spot, as if waiting for a show of resistance, as if hoping for a contest, as if rather insulted that it was all so routine. When he finally puts the ball in the net, rather than leaping in the air or embracing his colleagues, he grabs the goal post and nuts it, apparently angered by the ease of it all.

So it was in Richmond. You could see it on his face: what was the bloody point? He started by insulting the dress sense of a man sitting on the front row, asking him if he had nicked that suit out of a dead mans coffin. He then proceeded to mock the questioners, dismissing their queries with a sarcastic snort. He chuckled constantly to himself, finding his rude responses invariably hilarious. At least somebody did.

For a man who boasted an IQ of 154, this was not the brightest of demonstrations; his answers were by turns grumbly and mumbly. Never mind that his public had paid good money to spend time in his company; he showed little intention of delivering any return on their investment.

Sensing that his partner was in the sort of disruptive temper he had seen all too often, Marsh moved the agenda on. He called out from the wings the third speaker on the programme, the man who was meant to be a highlight of the evenings second half. It was Jack Charlton, Englands World Cup-winning centre back, who in his retirement had mastered the art of crinkly anecdotage. If any man could haul things back on track, Marsh clearly thought, Jack could.