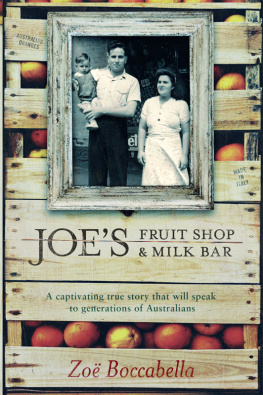

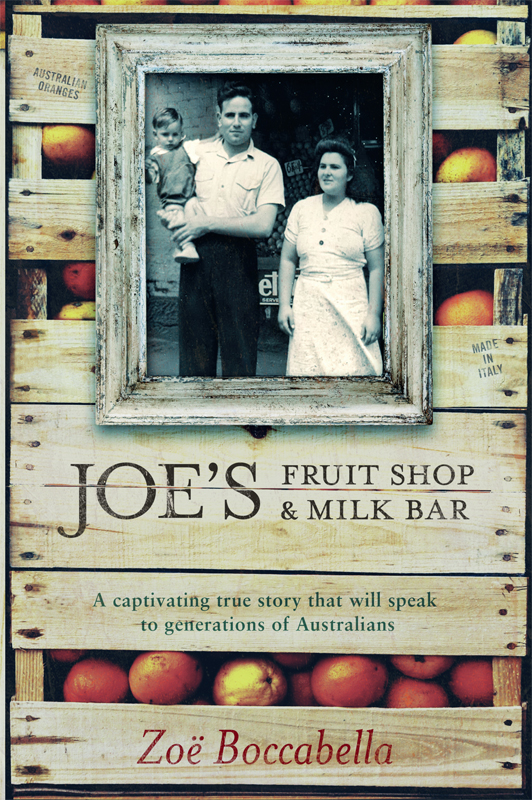

It runs with a rhythm through my mind, almost like the line of a song. I can still hear my grandmother Francesca drawing out each syllable in her Italian accent as she shouted, Ah-knee-bal-lee , from the top of the back steps when shed put the pasta on. And yet even as a little girl I understood Australians generally knew him as Joe.

Back in the 1940s, a friendly local had dubbed him with that name when he deemed Annibale too hard to say. My grandfather seemed content with this, introducing himself as Joe to most Australians from then on. He accepted it in the same way he adapted to many changes when he migrated to Australia (though he wouldnt contemplate changing his surname). And being nicknamed or adopting a more Anglo-sounding first name certainly wasnt unusual for migrants starting a different life in English-speaking countries.

Whats in a name? Depending on the language in which it is spoken, rose can be rosa , ros , roos , rza , re A ruse. Behind a nickname, a name nicked. A person may remain the same regardless of whether a word more palatable to another tongue is found to identify them. Or perhaps the name partly shapes its bearer. I sometimes wonder what my feisty great-granny Maddalena would have thought, considering she chose the name Annibale for her firstborn. She farewelled a fifteen-year-old son, known as Annibale, from Italy in 1939, to be reunited in Australia, almost a decade and a World War later, with a grown man most people called Joe.

By then his life had become immersed in Australia. He had worked on fruit farms, cut sugarcane and waited tables in a Greek caf. Hed overcome the challenging war years when he was interned and later blacklisted putting them behind him as he had the poverty hed left in Italy; yet still carried those experiences as part of him, just as his birth place remained in his heart too. And by this time, he had a wife and a son of his own who was born in Australia, forever connecting them to this country where they were now citizens. Together they were realising the dream Annibale had brought with him to Australia to open a business as it happened, a fruit shop and milk bar.

It was a time when everything was changing and anything seemed possible. Life was tough but you could still chase your dreams.

Brisbane 1946

They stood in the shade of an awning that spanned the footpath, gazing at 365 Ann Street. The shop frontage of white-painted brick was roughly fifteen feet across. On the right, several steps led up into the shop, and on the left was a shuttered window, without glass but with a large shelf area beneath it just right to display wooden crates of produce.

Its small. Francesca held the handle of the pram in one hand to keep it still as baby Remo kicked. She glanced again at the newspaper in her other hand, folded open to the ad offering a fruit-shop lease for three hundred pounds.

Annibale manoeuvred the pram to park it against the wall, out of the way. But therere lots of passers-by. He moved towards the door, which the agent had left unlocked for them. With a faint frown, Francesca tucked the newspaper in her handbag and lifted Remo into her arms.

Inside smelled of seasoned brick and dust on wood. There were two small rooms with ten-foot ceilings, one in front of the other, connected by a doorway. Given the narrow opening, it would be impractical to use both rooms and the front room alone was too cramped to contain a fruit shop and milk bar. They realised it was not so much a shop as a hole in the wall. Annibale began tapping on the wall between the two rooms.

Its too small, Annibale. Francesca swapped Remo to her other arm to take his weight. Well find something else.

Lets just have a look at the rest of it.

At the back of the shop, Annibales roving gaze alighted on a landing he realised could work well as extra storage space. Steps led down from it to a courtyard around the side and he began envisaging where he could stack fruit boxes and keep the bins. The courtyard had its own entrance from Ann Street: a lockable timber-framed door covered in sheets of corrugated iron. Still carrying Remo, Francesca followed Annibale through it and back out onto the busy footpath. Her eyes instantly went to the pram to make sure it was still there, and as Remo was starting to wriggle she put him back into it. Annibale drew up beside her and they stood looking at the area around them, silently assessing.

The shop sat in the northeast section of Brisbanes central business district, in a block of buildings owned by the Church of England. With St Johns Cathedral a little further up the street on the same side, and St Martins Hospital in between, churchgoers along with hospital workers and visitors would make up a large part of the passing trade. In the same building as the shop was the Speedometer Screenwiper Service, whose door opened directly on to the corner of Ann and Wharf Streets. Down the hallway that separated it from the shop was a photographer, WA Jones, who promoted his services by tacking up his portraiture in a glass-fronted case on the outside wall next to the shop. At the end of the hallway, stairs led up to a tailor by the name of Epstein and, directly above the shop, a boot repairer with the surname Bleakley.

Looking back along Ann Street towards the CBD, Annibale could see the clock outside Central Station across from Anzac Square. Across from the shop building stood a hotel on the corner of Wharf Street, and further along was a boarding house. Opposite, Annibale saw on the other side of Ann Street a hulking russet-brick building with sash windows and four tall garage doors, one open and revealing a blunt-nosed fire truck. His gaze moved from the Fire Brigades headquarters to a row of shops including a chemist and a snack bar, with rooms to let above.

The footpaths thrummed with men in hats carrying Gladstone bags and women toting brown-paper-wrapped parcels trussed with string, some donning gloves, others tugging the hands of resisting children. Young men back from the war passed too, some with empty sleeves or trouser legs pinned up; migrants still wearing the dark, heavier fabrics of Europe strolled by, older men smoking, the reflection in their spectacles concealing their gaze.

Feeling a small flutter of excitement deep inside, Annibale knew he wouldnt regret talking Francesca into moving to the Queensland capital to try their luck, even though they had a six-month-old baby and could have made a life on her parents Stanthorpe farm. Breathing in the jumbled scents of warm bitumen, meat frying in a Greek caf, truck fumes and the sweetness of Brisbanes subtropical air, already Annibale knew he could never go back to life on the farm. He turned to Francesca, eyes blazing.

Francesca showed him how to write 6th June, 1946 in English after his name when he signed the contract. Later that morning, Annibale went in to work his shift at the Astoria Caf and gave his notice, saying he would be starting up a fruit shop and milk bar. The Greek manager, Milos, put out his hand and wished him all the best. Therell always be a job for you here, but I doubt youll need it.

Annibale and Francesca opened the shop at the start of their third week in Brisbane.

Brisbane 2011

It has been raining for most of the summer immense, sheeting downpours easing to a drizzle before returning to a monsoonal deluge. After nearly a decade of drought, when dam waters dwindled and severe water restrictions caused tanks to become commonplace in backyards, the inundation is a reminder that Brisbane borders the tropics. Humidity soars close to a hundred percent. Everything feels damp clothes, carpets, bare skin, the pages of books. A rain-cloud pall hangs so dense its necessary to turn on lamps during the day. The grassy area around the Hills hoist and the banana and coffee trees becomes a quagmire. Little waterfalls splash over stone garden walls. December 2010 has been Brisbanes wettest recorded since 1859.