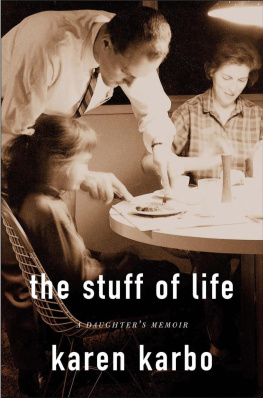

the stuff of life

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Fiction:

Trespassers Welcome Here

The Diamond Lane

Motherhood Made a Man Out of Me

Nonfiction:

Big Girl in the Middle (coauthor, with Gabrielle Reece)

Generation Ex: Tales from the Second Wives Club

the stuff of life

A DAUGHTER'S MEMOIR

karen karbo

BLOOMSBURY

For Fiona

in whom the spirit of Granddad-in-Nevada lives on

Author's note: The names and identifying characteristics of some of

the people in this story have been changed.

Copyright 2003 by Karen Karbo

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced

in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the

publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical

articles or reviews. For information address

Bloomsbury Publishing, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010.

Published by Bloomsbury Publishing, New York and London

Distributed to the trade by Holtzbrinck Publishers

All papers used by Bloomsbury Publishing are natural, recyclable

products made from wood grown in sustainable, well-man%ged forests.

The manufacturing processes conform to the environmental regulations

of the country of origin.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition as follows:

Karbo, Karen.

The stuff of life : a daughter's memoir / Karen Karbo.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-1-59691-825-2

1. Karbo, Dick. 2. Lungs-Cancer-Patients-United States-Biography.

3. LungsCancerPatientsFamily relationships. 4. Karbo, Karen. I. Title.

RC280.L8K375 2003

362.196'699424'0092-dc22

[B]

2003045135

First published in hardcover by Bloomsbury Publishing in 2003

This paperback edition published in 2004

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Typeset by Palimpsest Book Production Limited,

Polmont, Stirlingshire, Scotland

Printed in the United States of America by Quebecor World Fairfield

Contents

The threat of dying ought to make you witty.

Anatole Broyard

The call comes at eight-thirty on Sunday morning.

I'm already at my desk in the sunroom, still wrapped in my coffee-stained bathrobe. White had seemed like such a good idea, so clean and spalike. A flock of irate starlings chitters madly in the fig trees outside, battling squirrels for overripe fruit. The figs are deep maroon, rudely testicular. The sunroom opens out from the living room, where Rachel, Danny, and Katherine, still in their pajamas, are lined up on the sofa, flannel thigh to flannel thigh, watching Animal Planet, and squabbling over the remote. The television sits on a blond wood trolley meant for kitchen use, on the other side of the French doors, about two feet from my head. The current segment tells the story of a blind Labrador retriever that looks like our own Lab pup. Katherine keeps shrieking, "Mom! Come look! It's Winston on TV!" By the time I push back my chair, pull my robe tighter around me, and take the six steps to the television, I miss it.

"In fifteen minutes I'm going to make banana waffles," I tell them, just as I've told them every fifteen minutes for the last hour, thinking in another fifteen minutes I'll be able to figure out how to rewrite in one month a novel about motherhood that's taken me six years to sell. I'm hoping there's an easy fix, a single, kitchen-sampler-size bit of wisdom that's eluding me. Of course, it's the easy fix that's eluding me. The problem is a common one. The main character, a thirty-five-year-old woman named Brooke, is too, quote unquote, whiny, a charge leveled against every educated female character in contemporary literature who has a good job, a man in her life, all her limbs, and an ax to grind. I don't know how to make Brooke any different: She is the alpha breadwinner in the marriage, has just given birth to baby Stella, and cannot get her adorable husband, Lyle, to stop eating Extra Hot Tamales and playing computer games. (Actually, Brooke doesn't mind much about the Extra Hot Tamales; they give Lyle's breath a nice, cinnamony tang.) Her life is one she chose; still, sleep deprivation is sleep deprivation and a slacker husband makes one feel as if one has another child underfoot. The first chapter is due on the desk of Lydia, my no-nonsense literary agent, tomorrow morning, to be included in a booklet she is taking to the Frankfurt Book Fair. Perhaps the Germans or the French will not find Brooke too whiny. Perhaps they will think she has esprit, or whatever the German word for that is.

From the ratty forest green and maroon brocade couch a bad purchase; I was so focused on the ability of dark brocade to hide dirt, I forgot all about the two sofa-addicted dogs and their longish, thread-tugging toenails Danny yells, "Katherine! That was my show." Danny's devotion to AnimalPlanet is complicated, all tied up with his attachment to his mother, my husband Daniel's second ex-wife, who lives in central California and has dedicated her life to raising llamas.

"It's a commercial," says Katherine, voice of disdain and reason. At seven she is tall, opinionated, censorious. She wants to be a judge or a horse trainer when she grows up. She already knows commercials are things that try to sell you stuff you don't want. What confuses her is that after she sees a commercial, she does want it.

"I like the commercials!"

"Mom, when are you going to make the waffles?" asks Katherine.

"I don't care for bananas," says Danny. Where did he pick up this quasi-British locution?

I also have the rewrite of a magazine piece due tomorrow. Two months earlier, I spent several days at the San Francisco School of Circus Arts with a cadre of Silicon Valley software wizards who take time out of their ninety-hour work weeks to learn trapeze flying. The story is for a business magazine, and my gymnastic directives for the rewrite involve strengthening the currently nonexistent connection between the rush/risk/ gratification of trapeze flying and the rush/risk/gratification of launching a start-up in your garage.

When the phone rings, I'm startled. No one calls this early. I see my father's Nevada phone number on the Caller ID box and my insides are like dough being rolled flat by a baker who lifts weights.

It can only mean one thing. It can only mean he's dead or she's dead. DadandBev are the kind of people who are polite to a fault, people who feel it's rude to phone on the weekend before noon. They treat long distance as if it were something only to be broken out in an emergency, like the red fire extinguisher bolted to their kitchen wall.

"Kare?" came the voice, breathy, barely there.

Usually my father's voice is deep and hail-fellow-well-met, just this side of FM DJ quality, but he is not a talker, and his telephone voice is like a dinner jacket he puts on for a special occasion. When he makes a phone call, he always identifies himself by saying, "Dick Karbo here!" a locution that sounds as if it belongs to a superhero receiving a call for help in a phone booth. But the man on the line this time is not "Dick Karbo here!," it's someone in the throes of an asthma attack, someone weak and gasping, calling me from a faulty telephone exchange in an undeveloped country. Someone far away.

I know this voice, even though I've only heard it once, twenty-three years before. The tears squeeze against the inside of me. The afternoon my mother went into a coma, two days before she died, my father called on the house phone of the sorority house where I lived my freshman year at the University of Southern California. It was one phone used by about a hundred girls. I answered it more than most girls, who had their own phones in their rooms. My father was only forty-six then, but it was the same breathlessness, the same helpless mewl. These days, people barely consider forty-six middle-aged.

Next page