How Georgia Became

OKeeffe

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

FICTION

Motherhood Made a Man Out of Me

The Diamond Lane

Trespassers Welcome Here

NONFICTION

The Gospel According to Coco Chanel: Life Lessons from the Worlds Most Elegant Woman

How to Hepburn: Lessons on Living from Kate the Great

The Stuff of Life: A Daughters Memoir

Generation Ex: Tales from the Second Wives Club

Big Girl in the Middle (co-author, with Gabrielle Reece)

FOR YOUNG ADULTS

Minerva Clark Gets a Clue

Minerva Clark Goes to the Dogs

Minerva Clark Gives Up the Ghost

skirt! is an attitude... spirited, independent, outspoken, serious, playful and irreverent, sometimes controversial, always passionate.

skirt! is an attitude... spirited, independent, outspoken, serious, playful and irreverent, sometimes controversial, always passionate.

Copyright 2012 by Karen Karbo

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed to Globe Pequot Press, Attn: Rights and Permissions Department, P.O. Box 480, Guilford, CT 06437.

skirt! is a registered trademark of Morris Publishing Group, LLC, and is used with express permission.

Grateful acknowledgment to the Georgia OKeeffe Museum, the Museum of Modern Art, the Art Students League of New York, the Art Institute of Chicago, Wadsworth Athaneum Museum of Art, and the Museum of Fine Art of St. Petersburg, Florida, for making possible the inclusion of artwork by Georgia OKeeffe.

Text design: Sheryl P. Kober

Layout: Mary Ballachino

Project editor: Kristen Mellitt

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN 978-0-7627-7131-8

Printed in the United States of America

E-ISBN 978-0-7627-8585-8

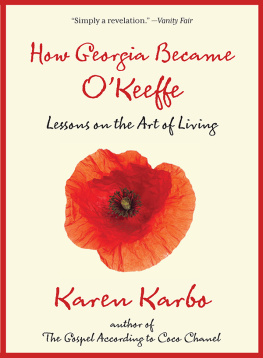

Georgia OKeeffe

American (18871986)

Poppy, 1928

Oil on canvas

Gift of Charles C. and Margaret Stevenson Henderson in memory of

Jeanne Crawford Henderson 1971.32

Photograph by Thomas U. Gessler

DEFY

I dont see why we ever think of what others think of

what we doisnt it enough just to express yourself.

When Georgia became OKeeffe there were no female art stars in America. Not one. In 1916 Georgia was an art teacher because thats what arty girls did. When she was twenty-eight, she was hired by West Texas State Normal College in the minuscule town of Canyon, Texas, due south of Amarillo. In Canyon there were a few churches, a few bars, a feed store, a blacksmith, a lot of cattle, and not much to do for sport but club rabbits. When Georgia arrived to assume her role as the entire art department, oil had yet to be discovered. Canyon was a flea on the immense dusty hide of the Texas prairie. Georgias students were the children of cattle ranchers. They sat on packing crates because there were no chairs.

Then, as now, staring down the barrel of thirty made many single women a little hysterical. A woman without a husband was a woman without a meaningful life. From all evidence this does not seem to have been the case with OKeeffe. She could not have cared less. If there was a contest for making yourself as unattractive to the opposite sex as possible, Georgia would be the darling of the oddsmakers.

As a young woman she dressed as she would all her lifein long black dresses that resembled the vestments of a priest. Occasionally she went in for a white collar. When she was really in a crazy mood, she was known to pin a flower to her lapel. She was a stranger to makeup and wore her black hair pulled straight back from her face. Here, I feel the impulse to offer some details about the fashions of 1916, but it hardly matters. Whatever women were wearing in those days, this wasnt it.

Georgias behavior was equally unconventional. The West may have been wild, but Canyon prided itself on its propriety. Ladies were expected in church on Sunday and at tea parties during the week. It didnt take much to create a stir. Georgia asked her landlords whether she might paint the trim in her attic room black, and before you could say Dont they have anything better to gossip about?, word spread that the new art teacher wanted to paint her entire room black. She ignored both church and teas, preferring to spend her time walking into the sunset. The extreme panhandle landscape had seduced her. Every night after dinner she left town and walked west toward the orange sun easing down the back of the sky to the brown horizon. It was said she could outwalk any man. She could outlast him in that cheek-chapping middle of nowhere, reveling in the color of the sky.

It wasnt as if she had some disorder that made her clueless about the societal expectations of the day. She knew what people thought; she just didnt care. In a letter to her new friend Alfred Stieglitzthe so-called father of modern photography, and the man without whom the name Pablo Picasso would mean nothing to usshe wrote, When there are so many things in the world to do it seems as if a woman ought not to feel exactly right about spending a whole day like Ive spent todayand stillit did seem rightthats what gets meit must be doneand if any one asked mewhat it isI can not even tell myself.

Lest you imagine Georgias refusal to gussy herself up, her general bookish nature, and her compulsive need for a daily miles-long hike made her unattractive to men, think again. Georgia was rarely without suitors. By the time shed taken the Texas teaching job in 1916, shed already enjoyed several torturous, passionate love affairs. Arthur Whittier Macmahon, a well-heeled intellectual from Columbia University, bewitched by Georgias perception of the natural world (it was a heady romance), wrote to her daily.

In Canyon, the local attorney, a Yale man, liked to take her for long drives on the prairie. She even enjoyed a vigorous flirtation with a student, Ted Reid, whom she met while serving as the artistic advisor for the drama departments spring play. Reid was handsome and popular; even in those days, a star football player who also loved theater held a special appeal.

Reid was a student, OKeeffe was a teacher. He was on one side of the twenties, she was on the other. In one account of these years, Reid was already engaged to the woman who would become his wife. On Saturdays Reid drove OKeeffe to nearby Palo Duro Canyon (The Grand Canyon of Texas, as it still bills itself), where they would pick their way to the bottom on the narrow cow paths, and OKeeffe would sketch the cliffs, the sky, the occasional string of cattle that would wend its way into the canyon, seeking shelter against the merciless panhandle wind.

The townspeople tolerated what was, for the time, fairly shocking behavior, until the afternoon when OKeeffe invited Ted Reid up to her room to see some photographs that shed recently received from Stieglitz. This outrage was the last straw. When the gossip swirled throughout Canyon that the art teacher was entertaining one of its finest young men in her rented attic room, something happened that neatly makes the point Im after herethat even before Georgia was OKeeffe, when she was a near old maid trying to make ends meet, her determination to live life her own way afforded her an enviable freedom. If it were anyone else, shed have been run out of town on a rail, but Reid was the one who received a stern talking-to by the local matrons, Reid who was told his behavior was inappropriate and unacceptable.

skirt! is an attitude... spirited, independent, outspoken, serious, playful and irreverent, sometimes controversial, always passionate.

skirt! is an attitude... spirited, independent, outspoken, serious, playful and irreverent, sometimes controversial, always passionate.