ALSO BY CAROLYN BURKE

No Regrets: The Life of Edith Piaf

Lee Miller: A Life

Becoming Modern: The Life of Mina Loy

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2019 by Carolyn Burke

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library for permission to reprint text excerpts from letters by Georgia OKeeffe to Alfred Stieglitz, from Alfred Stieglitz/Georgia OKeeffe Archive. Copyright 2011 by Yale University. Reprinted by permission of the Yale Collection for American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library. All rights reserved.

Names: Burke, Carolyn, author.

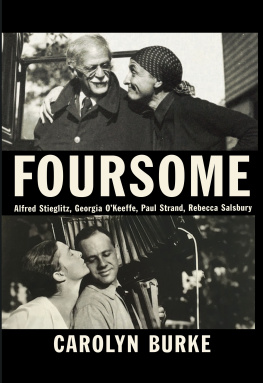

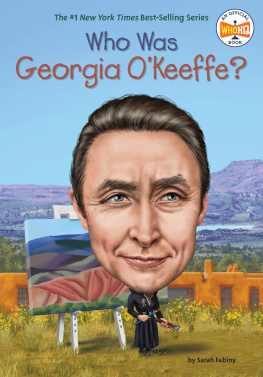

Title: Foursome : Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia OKeeffe, Paul Strand, Rebecca Salsbury / by Carolyn Burke.

Description: First edition. | New York : Alfred A. Knopf, 2019. | This is a Borzoi book published by Alfred A. Knopf. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018016794 (print) | LCCN 2018020035 (ebook) | ISBN 9780525655367 (ebook) | ISBN 9780307957290 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH : Artist couplesUnited StatesBiography. | Stieglitz, Alfred, 18641946. | OKeeffe, Georgia, 18871986. | Strand, Paul, 18901976. | James, Rebecca Salsbury, 18911968.

Classification: LCC TR 140. S 7 (ebook) | LCC TR 140.S7 B 87 2019 (print) | DDC 770dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018016794

Ebook ISBN9780525655367

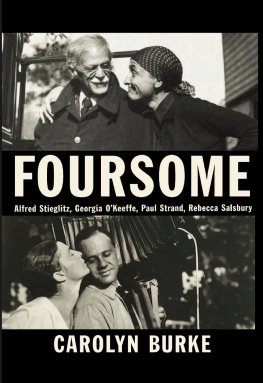

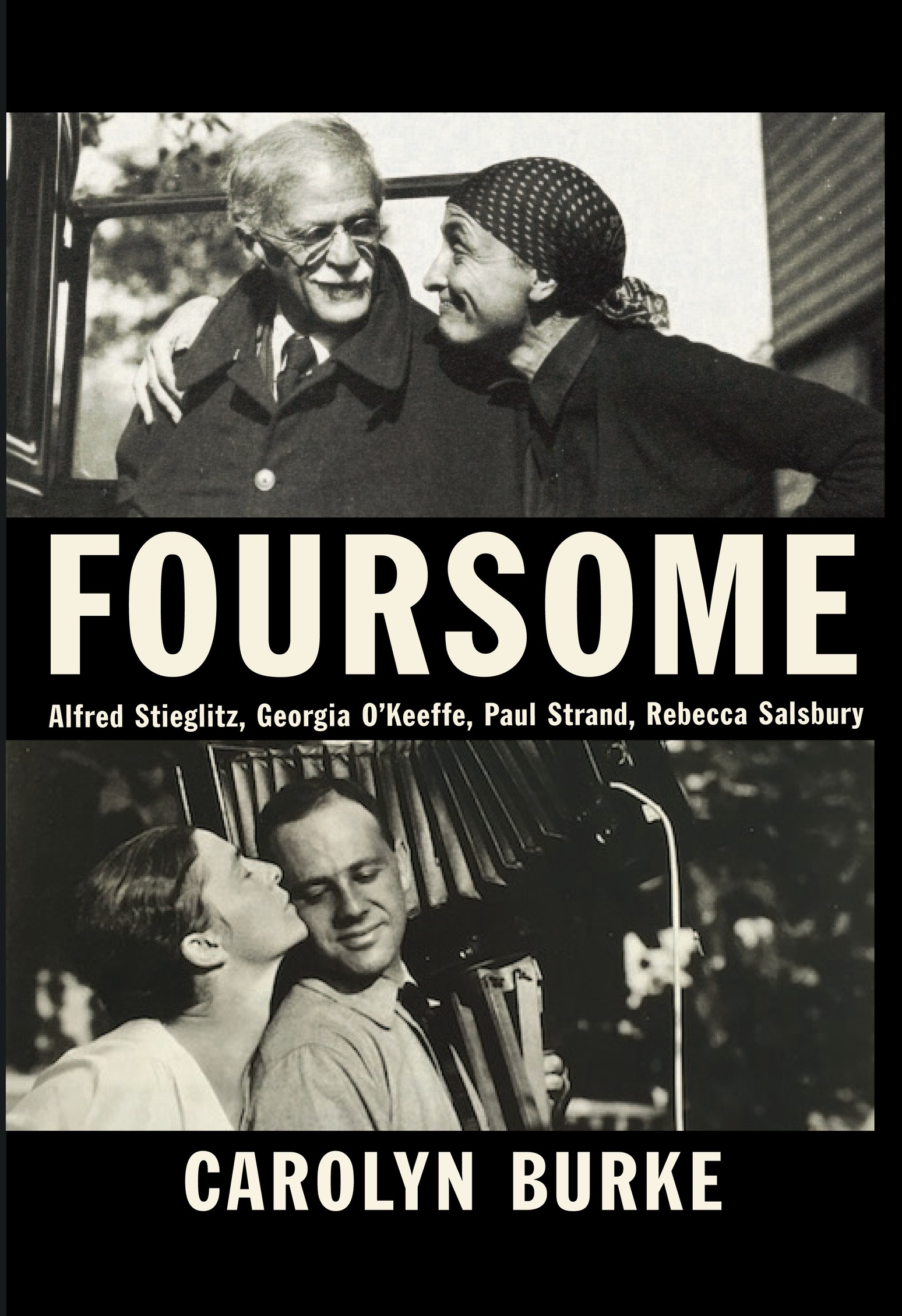

Cover images: (top) Alfred Stieglitz and Georgia OKeeffe, 1936. CSU Archives/Everett Collection; (bottom) Paul Strand and Rebecca Salsbury at Lake George, c. 1923 by Alfred Stieglitz

Cover design by Carol Devine Carson

v5.4_r1

ep

For Robert Gottlieb, avid reader

Contents

This book would not have come into being without the wholehearted collaboration of Lance Sprague. From the outset its interwoven narrative drew on his love of early photography and his insights as a practicing artist. In the seven years it took to write, he gave abundantly of his time, complementary talents, and irreverent sense of humor, particularly valuable on research trips. We often surprised each other, especially when processing the thousands of documents brought back from the archives. Together, we came to understand the convergences and divergences of our foursomes lives: I learned as much from him about the impact of aesthetic choices on private life as I did from our subjects. His artists eye helped us select images to retell the story visually; our ongoing dialogue enabled us to grasp affinities in the foursomes artistic practice and imagine ways for readers to experience those complementarities through the choice and arrangement of the illustrations. For this and many other reasons, including his role as writers accomplice, it is as much his book as it is mine.

Alfred Stieglitz often said that taking photographs was like making love. The crowds that flocked to the Anderson Galleries to see his work in the winter of 1921 could not fail to note the entwining of creative zest and sexual desire in his portraits of an unidentified Woman: This study of his model, dressed and undressed, made up a third of the long-awaited exhibition. Within days, it became the most controversial artistic event of the year. Never was there such a hub-bub about a one-man show, a sympathizer recalled.

In the aftermath of the recent Red Scare and Hardings election to the presidency, Stieglitzs prints looked like an affront to society. To some critics, they were all but un-Americanthe artists way of flouting Hardings plan to bring back prewar standards. (The countrys greatest need, Harding had repeated during his campaign, was not nostrums but normalcy; not revolution but restoration.) In the current political climate, the photographers assertion of his right to display life uncensored was an act of defiance. Stieglitz has not divorced his art from life, a critic wrote. If one were to find fault with his show, it would be with its lack of reticence. Stieglitz, he concluded, keeps nothing back.

On opening day, February 7, after braving the icy winds blowing down Park Avenue, Manhattans cognoscenti gathered beneath the skylights on the fourth floor of a neoclassical building on the corner of Park Avenue and Fifty-ninth Street. Contemporary reports describe them standing as still as if they were in church. After the closing four years earlier of 291, Stieglitzs gallery (where New Yorkers first saw the most provocative modern artists), some thought that he had given up photography and his role as a guiding force in American culture. Recently, word had gotten around that he had been reinvigorated by his love for the artist Georgia OKeeffe, that his photographs of heridentified only as A Womanwere sensational. His resurrection, a critic announced, is a staggering phenomenon, and in its clat, dazzling.

Visitors entered the first room with a sense of anticipation. The photographers warm-toned blacks and whites glowed so intensely against the red plush walls that some wanted to touch them. Stieglitz was holding forth in a corner, telling spellbound listeners about his struggle to win acceptance of photography as an affirmation of life. Gazing at his prints of ManhattanFifth Avenue swirling with snow, cabdrivers watering their horses, Central Park on an icy nightpeople marveled at his way of letting life be life, as he was heard to say.

Others were drawn to his scenes of modernitybackyards strung with clotheslines, half-finished construction sites, railroad yards in the snow. His recent work went beyond what was called art photography, eschewing the pictorialist techniques then in vogue to reveal the subject itself. They make me want to forget all the photographs I had ever seen before, a critic declared.

Moving into the next room, which was filled with portraits, visitors lingered over those recalling the great days of 291. Members of the Stieglitz group studied his prints of their circle: the artists John Marin, Marsden Hartley, and Charles Duncan; the critics Leo Stein and Paul Rosenfeld; and the West Indian writer Hodge Kirnon, who had run the elevator at 291. Stieglitzs surrogate son, the photographer Paul Strand, stared back at those who stopped in front of his likeness on their way to the pictures of the notorious Woman.

Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia OKeeffeTorso, 1918

They encountered her in a grouping that showed her before one of her charcoal drawings. Dressed in a trim black jacket and hat, she looked away from the cameraa portrait of the artist as a young woman. Moving around the room, visitors met her in more intimate posesher hat off, her tailored blouse unbuttoned, her dark tresses undone. In a warm palladium print, she reappeared in a white kimono whose delicate pattern complemented the dark tones of her hair. Studies of her elegant hands and fingers were grouped as a single portrait, as if these parts expressed the woman as a lover and an artist. On another wall, her hands touched her voluptuous breasts, weighing their contours or pressing them togetherin a group labeled forthrightly, Hands and Breasts. Another set of sepia-toned prints, Torsos, compared her body to sculpture while simultaneously drawing the gaze to the dark V shape of her pubic hair.