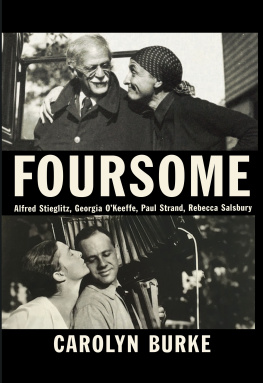

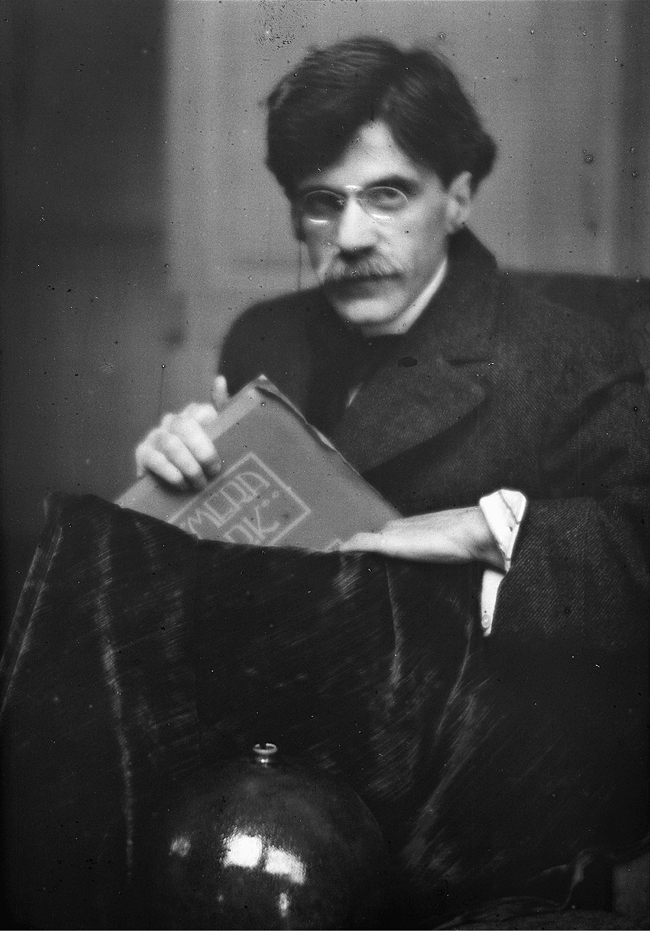

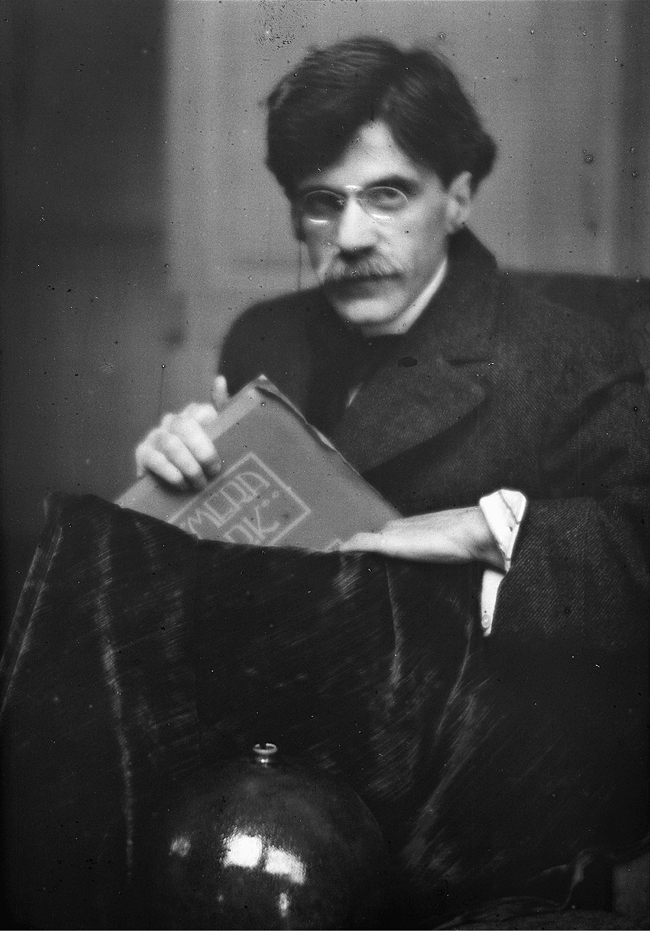

ALFRED STIEGLITZ

Edward Steichen, Alfred Stieglitz, 1907. (Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1955. Image copyright The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY. 2018 Estate of Edward Steichen/Artists Rights Society [ARS], NY.)

Alfred Stieglitz

Taking Pictures,

Making Painters

PHYLLIS ROSE

Copyright 2019 by Phyllis Rose.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Picture Research by Laurie Platt Winfrey, Carousel Research.

Set in Janson OldStyle type by Integrated Publishing Solutions.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018955013

ISBN 978-0-300-22648-5 (hardcover : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992

(Permanence of Paper).

To Mary Ryan, art dealer,

and to David Schorr, artist and educator

CONTENTS

Color illustrations follow

Prologue

S HORTLY AFTER his father died, Alfred Stieglitz, writing to a friend in his fluent German, praised Edward Stieglitz as a kunstmensch, an art man. He was celebrating his fathers cultivation, from which his own derived. Edward Stieglitz had emigrated from Germany to the United States in the wake of the European political upheavals of 1848. He made his living as a wool merchant but focused his home life on art. A serious weekend painter, the elder Stieglitz was the kind of man, rare now but more common in the nineteenth century, who looked forward to retirement as the fullest stage of life. When it seemed to him that his sons could not get a proper education in the States, he sold his business and moved the whole family back to Germany.

Alfred Stieglitz emerged from a middle-class European cultural tradition that may have been a high point of civilization. Men like his father, born in 1833, read Schiller, Goethe, and Shakespeare. They studied works by Rubens, Rembrandt, and Leonardo, followed contemporary art, read philosophy, and attended the theater. They were comfortable in several languages, played musical instruments, and enjoyed live performances of music in their homes. They educated their children to love music, art, and literature and to regard them as necessary components of their lives. I think of this period as the age of Ruskin, because Ruskin articulated the belief that art was a moral force, a belief that underlay and justified all this cultural activity. Art made people better; it was a force for the goodan idea dealt a terrible blow by World War I and another when the land of Beethoven became the land of Dachau.

Alfred Stieglitz spent close to ten years in Europe, from the ages of seventeen to twenty-six, studying engineering and chemistry, falling in love with photography and mastering the process. Most of all, he learned to live like a European. He loved Berlin for its cultural excitement and for the intellectual camaraderie he found there. When he first returned to America, he was miserable. The streets of New York seemed dirty and unpleasant, the people unsympathetic. Only the performances of Duse, the comedy of Weber and Fields, and the working horses he photographed made the American city bearable. He saw nothing but materialism, luxury, wastefulness, and self-satisfaction in American culture, and he feared that this blight would spread and infect his beloved Europe. Nevertheless, he was an American, born in New Jersey, and his fight, like the fight of Thoreau, Whitman, Emerson, and Lincoln, was to mold Americas spirit. For Stieglitz, the route to human emancipation was via the visual arts, and his goal was to show how people could derive from art the values that give life significance. He deployed this atheists religion in combat for the soul of America. His brother told him they had three rabbis in their ancestry. That didnt surprise Alfred, who always regarded himself as a teacher, spreading the word that art helped good prevail.

By the time he was sixty, accomplished and famous as a photographer, he had more or less given up photography and devoted himself to selling art which, for him, meant promoting art. His galleries, first 291, then the Intimate Gallery, and later An American Place, were not dealerships so much as open universities. There he stood, day after day, talking to whoever walked in. Like an ancient philosopher holding forth in a marketplace, he expounded his ideas, using the art on the walls to illustrate his points.

His contempt for conventional art dealers and collectors was fierce. Dealers were interested only in making livings for themselves, not in helping artists. Collectors never went for the greatest pieces but for the cheapest. He loved to tell stories of people passing up chances to buy masterpieces. At one point the trustees of the Metropolitan Museum of Art had refused a group of Rodins watercolors at what Stieglitz considered a ridiculously low price, on the grounds that they couldnt afford it. Now the watercolors could not be bought at any price. It was as if the Museum had been offered a thousand twenty-dollar gold pieces for a thousand dollars, and had a directors meeting and decided they could not afford the purchase, Stieglitz said.

He liked to talk about the career of Arthur Dove, who had been earning $15,000 a year doing illustrations for magazines like Colliers but had given it up to devote himself to painting. Doves father, a brick manufacturer, remarked that if his son could afford to give up that large an income, he didnt need anything his father could give him and cut him off without a cent in his will.

Stieglitz often compared artists to apple trees. As it was in the nature of apple trees to produce apples, it was in the nature of artists to produce art. Is there any trick about the trees taking up sap from the ground and bearing apples? The artist is like that. What the men shown in this room are putting down is feeling, life itself, a thing Americans are trying to run away from. If artists were like trees and plants, Stieglitzs job was that of husbandry, the cultivation of the bounty of nature.

When Stieglitz discovered John Marin, he was working in two styles, etchings in an imitative Whistlerian style, which were saleable, and etchings and watercolors in a different style, that we would come to think of as Marins, which were not as marketable. Stieglitz encouraged Marin to work in the more original style. Marins father came to see Stieglitz and asked if it would not be possible for his son to make saleable things in the morning and devote the afternoon to his other work. Stieglitz replied that if Mr. Marin had a daughter who could be a prostitute in the morning and come home a virgin in the afternoon, then Marin could do what his father wished.

A young man who said he wanted to be an art critic visited the gallery, and Stieglitz asked him what kind of critic he wanted to be. Did he want to be a Berenson who declared which works were fake and which were real? He, Stieglitz, knew which works were real because he had seen them from their birth. He knew them as he knew the trees of Lake George or Central Park. He had no need to surround himself with fakes and fakery, only with true things. Berenson was in fact something of a bte noire to Stieglitz. The two men were about the same age and both were prominent in the art world, but how differently they operated! Berenson helped the rich acquire; Stieglitz helped artists survive.

Next page