The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy .

Contents

For my parents and for the victims of the bombings in London on 7 July 2005 I have always dreamed, he mouthed, fiercely, of a band of men absolute in their resolve to discard all scruples in the choice of means, strong enough to give themselves frankly the name of destroyers, and free from that taint of resigned pessimism that rots the earth. No pity for anything on earth, including themselves, and death enlisted for good and all in the service of humanity thats what I would have liked to see. Joseph Conrad, The Secret Agent I have been called a sentimentalist. Its true. I was a journalist because, when I got up in the morning and read the paper, there were pieces of news in it that angered me. I wanted to express my anger as clearly as possible, but I was unable to do much more than that. I certainly didnt have a theory, much less a comprehensive ideology. I didnt want to go beyond the limits of what I was sure of. So I was considered unconstructive, irresolute, and a petty moderate. Still, I dont think I am ready to compromise on what makes me angry. Albert Camus

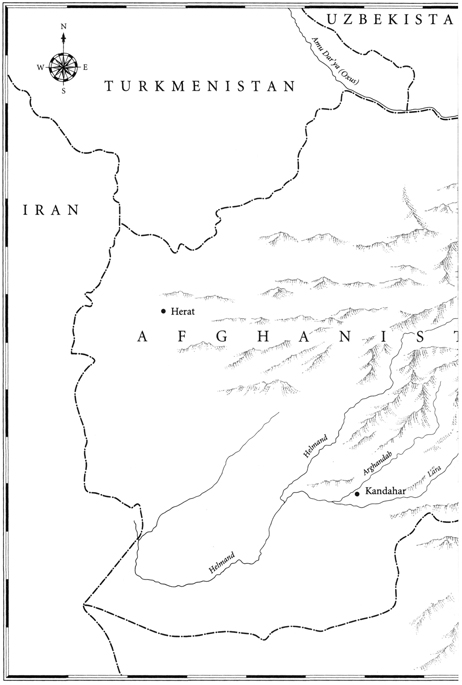

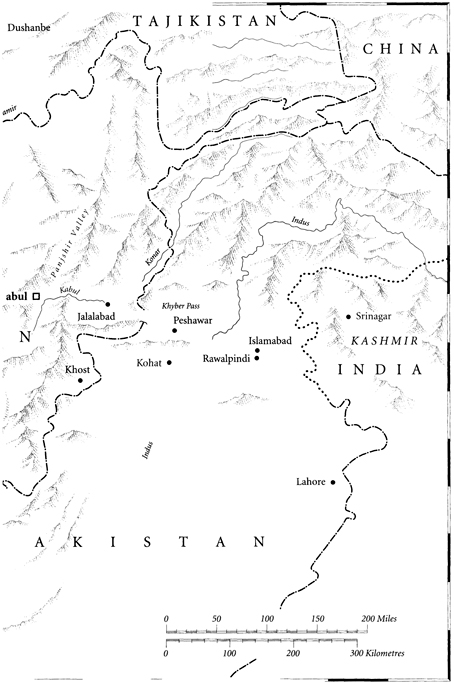

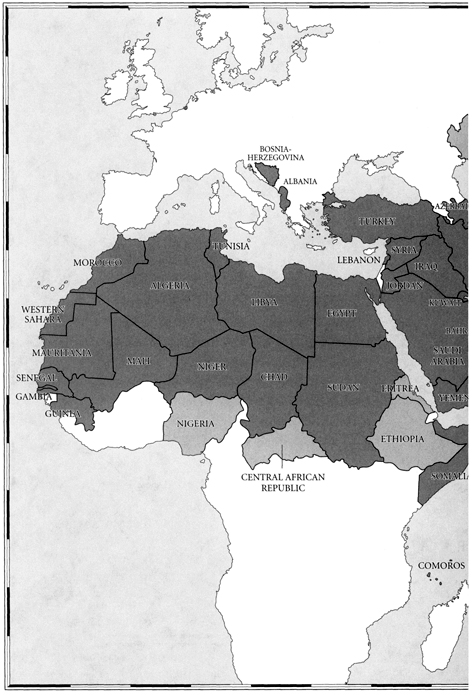

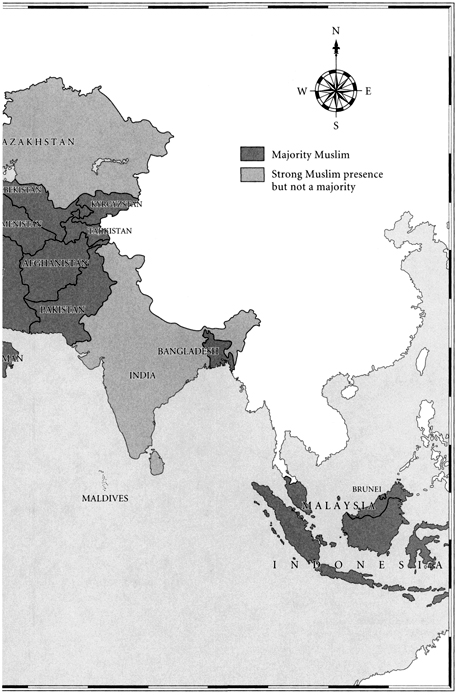

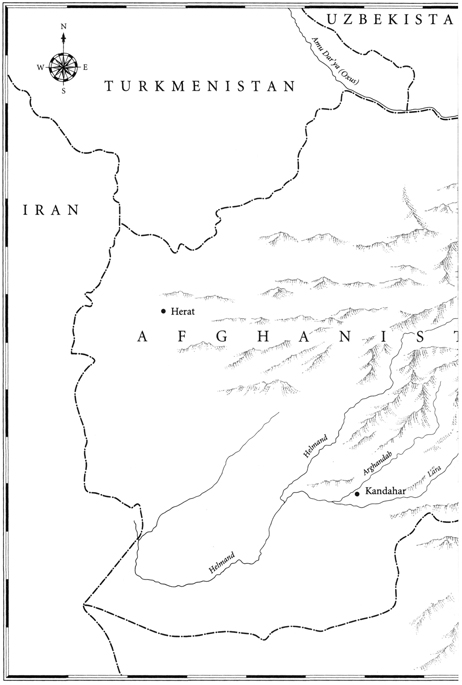

Maps

Introduction: I Was a Teenage Guerrilla

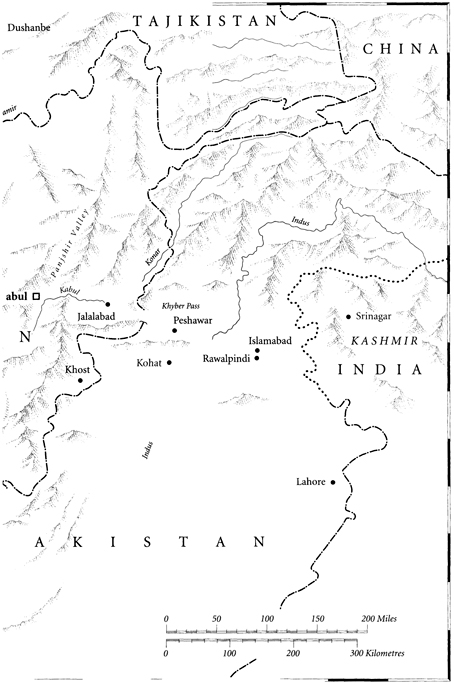

We buried the letter at the bottom of one of our bags and left the next morning, travelling west in a local bus on a bad road that led across high hills with slopes of pines broken by slabs of grey rock. Where there was shadow there were strands of dirty snow and, with the chill that came with evening, it was clear why so many refugees had died in the mountains when they had fled earlier in the year. We stopped overnight in a small village set on the lip of a deep gorge and stayed in a roadside hostel where we slept on the floor and were woken several times by gunfire. In the morning we ate thin yoghurt with warm bread and drank tea the colour of polished copper from small glasses and watched impassive local villagers lead heavily equipped troops through their fields and up into the higher hills. There was a big operation underway against the guerrillas, we were told. By the afternoon we were out of the mountains and on a straightening road down to the plains. There we were to give the letter to a man in the refugee camp in the desert outside the frontier town where several thousand families lived on United Nations aid. We found the man, who opened the letter, read it and told us that the best way to cross the border was simply to take a taxi. It would cost about $10 and take less than an hour. We were very disappointed.

Sometimes, when drunk or desperate to impress, I tell people I fought as a teenage guerrilla. Its not entirely true. I wasnt a teenager, I was 21. And, though I did carry a gun, I didnt fight. In fact, on the few occasions shooting started, I hid in a ditch.

It was the summer of 1991. Saddam Husseins ill-judged attempt to seize Kuwait and its oil had ended in swift and predictable defeat by an American-led military coalition a few months previously. In the wars aftermath, the Shia Muslim population of the south of Iraq rebelled, swiftly followed by the Kurds living in the north. Both believed that they would be supported by the allies. But the allies had stood by while Saddams tanks and helicopters dealt first with the Shias and then pushed the Kurds back into their historic mountain strongholds in a series of bloody battles which prompted more than a million refugees to head to the Turkish and Iranian borders. In all, at least a hundred thousand died.

To start with there was little that distinguished my trip, with a friend from university called Iain, from that of any other pair of second-year undergraduates backpacking round Europe. We hitched across Turkey, drank too much Efes beer and were delayed for some time in a cheap hotel in Cappadocia by two Danish girls. But on reaching Van, a city in the east of the country, the half-formed plan that neither of us had really discussed, though we both knew existed, began to emerge. We started, relatively carefully, contacting people who we thought might be able to help us meet the PKK, the local Kurdish Marxist guerrillas, then seven years into an insurgency in the mountains of southeastern Turkey. In fact, to have met them would have been very dangerous and we were gently persuaded of this by a carpet salesman in Vans main bazaar, who pointed out that the group had a habit of taking Western tourists hostage. He suggested an alternative: crossing the border into Iraq. There, in the north, the Kurds were on the brink of setting up a genuine independent state. This was more or less what we had hoped to do anyway.

He told us that we would have to travel to Hakkari, a rough and ready town 100 or so miles away, go to the Hotel Umit, ask for Achmed and say that Apple had sent us. We took the bus, found the old hotel not far from the centre of town and told Achmed about Apple. If the melodrama amused him, Achmed showed no sign of it. Within an hour we had been handed the sealed letter in a mouldy hotel room by two taciturn men who neither removed their overcoats nor sat down during the hour we spent with them. In the square outside Turkish troops jumped down from trucks and fanned out through streets full of market stalls, goats and old jeeps. From there, with our letter safely stowed, we headed through the mountains and down to the plains, the refugee camp and the border.

I had never been in a refugee camp before. It was noon and the sun came straight down and the dust blew hard across the open spaces between the tents. A crowd of women and children with an astonishing variety of containers jostled around a water tanker. I asked Iain if the lemon juice I had squeezed into my hair was making it blond and me more like the sun-bleached combat veteran I hoped to resemble. He said no. Because there was no post and telephones were too expensive several refugees gave us letters to deliver to friends and family which I promptly left in the taxi that took us to the border with Iraq the next morning. En route we passed an American base with long lines of armoured vehicles in neat ranks. At the border there were Kurdish soldiers, looking impossibly romantic in their beards, chequered headdresses, traditional baggy trousers, wide cummerbund-style belts and square tunic tops. A ragged banner slung over a portrait of Saddam Hussein that had been shot to pieces told us that we had entered Iraqi Kurdistan.

I would like to be able to say that I had a consuming interest in the Kurds and had wanted to be part of their struggle for a long time. I cant, however. I ended up with the peshmerga, or those who face death, as the Kurdish irregular soldiers are known, for a variety of reasons, none particularly noble but all fairly common to young men. I went to Iraq because I did not want to go backpacking in Thailand again or work in a supermarket warehouse all summer as I had done the year before, because I had just split up with my first serious girlfriend and wanted to make a point, and, perhaps most of all, because I hoped for some good stories to tell in the college bar. As I had wanted to be a journalist since I was 15 and had watched the pictures of the air assault on Iraq and the hundred-hour war that succeeded it on a small black and white TV in the rented house I shared with five other students through the previous winter, I could dress up what was basically a post-adolescent adventure as a rather extreme form of work experience. During the spring I had read and re-read the biography of Don McCullin, the great British war photographer whose iconic black and white images and troubled personal life seemed to me to be tragic, romantic, compassionate and harsh in equal measure. I bought a lot of film, took two very old cameras and a couple of lenses and a notebook and decided that Iraq was where I would make my name.

Next page