THE NEW THREAT

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Al-Qaeda:

The True Story of Radical Islam

On the Road to Kandahar:

Travels through Conflict in the Islamic World

The 9/11 Wars

2015 by Jason Burke

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form, without written permission from the publisher.

Requests for permission to reproduce selections from this book should be mailed to: Permissions Department, The New Press, 120 Wall Street, 31st floor, New York, NY 10005.

First published in Great Britain in 2015 by The Bodley Head

Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, 2015

Distributed by Perseus Distribution

ISBN 978-1-62097-136-9 (e-book)

CIP data is available

The New Press publishes books that promote and enrich public discussion and understanding of the issues vital to our democracy and to a more equitable world.

These books are made possible by the enthusiasm of our readers; the support of a committed group of donors, large and small; the collaboration of our many partners in the independent media and the not-for-profit sector; booksellers, who often hand-sell New Press books; librarians; and above all by our authors.

www.thenewpress.com

Printed in the United States of America

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

For Clara, and her great-grandmothers

CONTENTS

Guide

This book would not exist without the inspiration and enthusiasm of my agent Toby Eady or the commitment, hard work and skill of my editor Will Hammond at Bodley Head. It is, in a very real sense, theirs as much as mine. My thanks to them both.

I am grateful too to all those involved in the scramble to turn a rough manuscript into a handsome book in such record time, to all those involved in its marketing, and to Dan Kirmatzis particularly for his last-minute fact checking. All errors, of course, remain my own.

There are many, many people around the world who have translated for me, passed on contacts, shared their knowledge, made suggestions, kept me safe, told me when to duck, set up meetings, driven me, tolerated my driving, trusted me with their confidential views, or otherwise helped in two decades or so of journalism. I owe them an enormous amount, as I do the many editors at the Guardian and the Observer who have sent me off to listen, learn, see and write.

Victor and Clara will one day, I hope, understand why I had to forego drawing, hide and seek, cake baking, bike riding, tree climbing, swimming, and even football practice for month after month, and also how their laughter, enthusiasm, curiosity and mischief kept me going.

Above all, nothing would have been possible, or would be possible, without the love, support and encouragement of Anne Sophie.

No one was quite sure who was in charge of Mosul in the early summer of 2014. During the day, government security forces maintained a tenuous hold, but at nightfall they ceded the streets, squares and battered neighbourhoods of Iraqs second city to others.

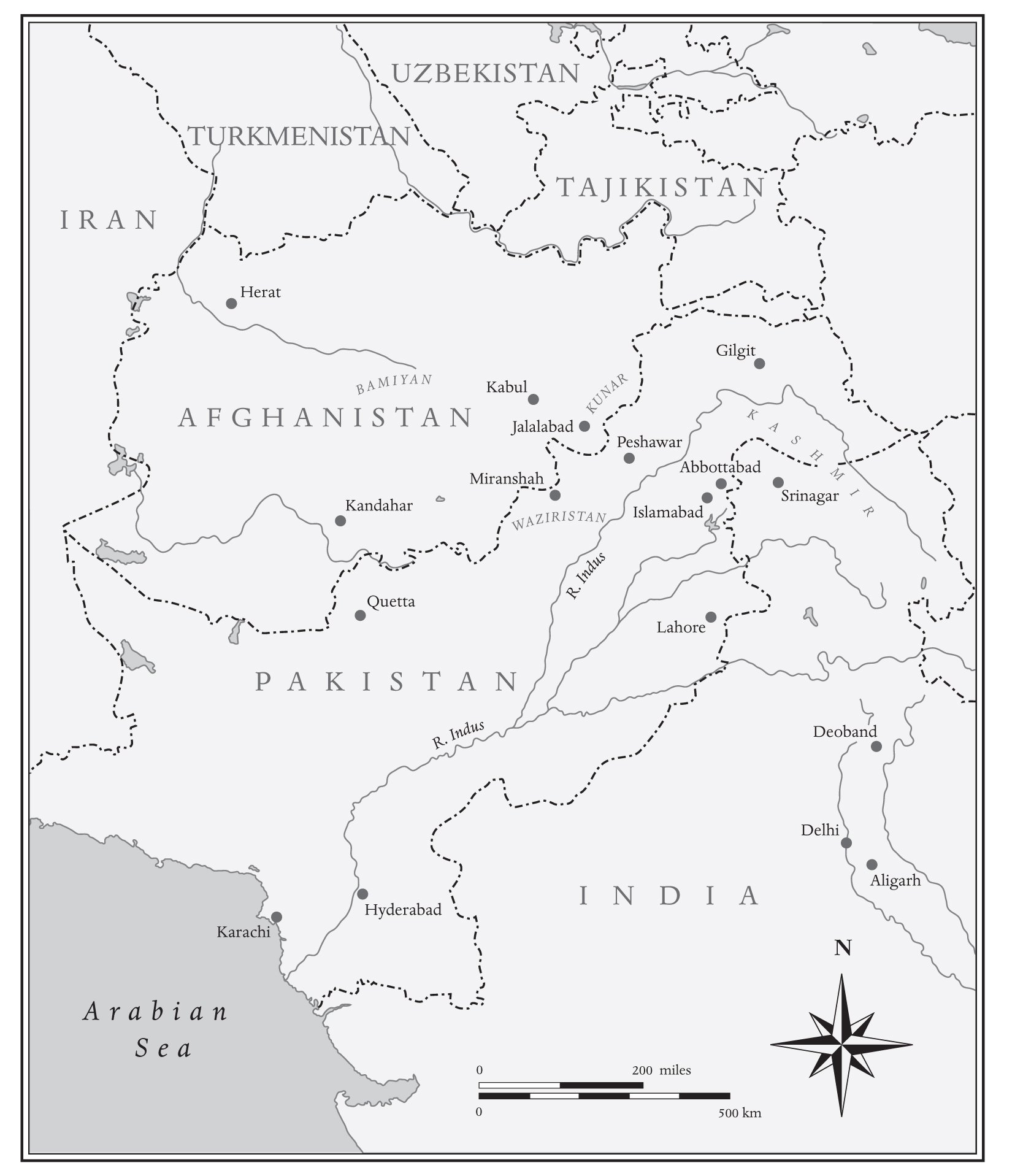

Mosul, the capital of Nineveh province, had long been a trouble spot, even as far back as the immediate aftermath of the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003. As a bastion of Iraqs Sunni Muslim minority, it maintained a tradition of support for Saddam Husseins Sunni-dominated regime. The deposed dictators two sons had taken refuge there, and Sunni militants had briefly seized control of it in 2004. The presence of many tightly knit military families and a long history of exposure to extremist religious ideologies combined with ethnic tensions and a complex tribal tapestry made the city of one million inhabitants a problem.

So when on the morning of 8 June Atheel Nujaifi, the governor of Nineveh, had a meeting with US officials, it took place in Erbil, a city dominated by Iraqs Kurdish minority sixty miles away. Mosul was deemed much too dangerous for Americans to visit. Indeed, it was increasingly dangerous even for the governor.

Nujaifi, appointed five years earlier, had alarming news. Over the previous three days hundreds of armed pickup trucks carrying Islamic extremist fighters had crossed the nearby border from Syria, which had been embroiled for more than three years in a brutal civil war. Having driven through the lawless tracts of scrubby desert to the west of Mosul, this sizeable force of Sunni militants was now assembled on the outskirts of the city. The Iraqi Army, controlled directly by Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki and almost exclusively Shia, had agreed to provide assistance, but no one in Baghdad, the Iraqi capital 270 miles to the south, seemed to appreciate the urgency of the situation and reinforcements might not arrive for a week.

As the Americans scrambled to assemble some kind of response, it became clear that events had overtaken them. Extremists had begun moving into Mosul more than forty-eight hours before. A massacre of policemen had prompted mass desertions, and a bid by government forces to clear outlying suburbs had failed. Tribal militias and local groups once loyal to Saddam had also joined the fighting, and a series of carefully targeted raids on jails freed hundreds who immediately swelled the militants ranks. In Baghdad, though, senior government officials had rejected an offer from Kurdish leaders to send their own forces into the city and reassured the US officials that Mosul was not under serious threat.

The full weight of the militant offensive came to bear, however, three days after the initial assault began. The few hundred fighters who had first infiltrated the city had by now become a force of between 1,500 and 2,000 as sympathisers rallied to their black flags in increasing numbers. A massive car bomb broke resistance at a crucial defensive position around an old hotel, almost entirely eliminating any organised resistance to the militants in the parts of Mosul west of the river Tigris. On 9 June, Nujaifi made a televised appeal to the people of the city, calling on them to form self-defence groups, stand their ground and fight. Hours later he fled, narrowly escaping from the provincial headquarters as police held off hundreds of militants armed with rocket-propelled grenades, sniper rifles and heavy-vehicle-mounted machine guns. Most of the senior military commanders had already deserted, and the two divisions of underequipped, undertrained Iraqi troops supposedly defending the city, totalling around 15,000 men on paper but perhaps only a half or a third of that in reality, disintegrated.

A small group of militants had routed a force of regular soldiers that was between three and ten times more numerous, itself part of an army of 350,000 on which somewhere between $24 billion and $41.6 billion, mainly US aid, had been spent over the previous three years. In scenes reminiscent of the US-led invasion of 2003, thousands of army soldiers dumped their weapons, stripped off their uniforms and ran. Several hundred were captured, and some were made to lie down in hastily dug trenches on the outskirts of the city and were shot. Soon Mosuls airport, its military airfield, banks, TV station, a major army base equipped with enormous quantities of weapons, munitions and US-supplied equipment were all in militant hands. By the afternoon, the battle for the city was over.