In memory of my father James Cumming

And for Elizabeth, Dennis, Hilla and Thea with all my heart

, Rembrandt van Rijn

, Jan van Eyck

, Jan van Eyck

, Jan van Eyck

, Jan van Eyck

, Jan van Eyck

, Sandra Botticelli

Sandra Botticelli

, Jacopo Comin Tintoretto

, Anton Graff

, Jean-Baptiste-Simon Chardin

, Rembrandt van Rijn

, Lorenzo Lippi

, Titian

, Sir Joshua Reynolds

, Paul Klee

, Francisco Jos de Goya y Lucientes

, Albrecht Drer

, Albrecht Drer

, Albrecht Drer

, Albrecht Drer

, Albrecht Drer

, Michelangelo Buonarroti

, Michelangelo Buonarroti

, Giovanni Bazzi (Il Sodoma)

, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

, Sir Anthony van Dyck

, Judith Leyster

, Nicolas Poussin

, Bartolome Esteban Murillo

, Felix Nussbaum

, Georges Pierre Seurat

, Rembrandt van Rijn

, Rembrandt van Rijn

, Rembrandt van Rijn

, Rembrandt van Rijn

, Rembrandt van Rijn

, Rembrandt van Rijn

, Rembrandt van Rijn

, Artemisia Gentileschi

, Orazio Borgianni

, Sofonisba Anguissola

, Arcangelo Resani

, Adelade Labille-Guiard

, Francisco Jos de Goya y Lucientes

, Philip Guston

, Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Velzquez

, Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Velzquez

, Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Velzquez

, Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Velzquez

, Jan Vermeer

, Parmigianino

, From De Claris Mulieribus by Giovanni Boccaccio

, Jean-douard Vuillard

, Lovis Corinth

, Johannes Gumpp

, Norman Rockwell

, Lucian Freud

, Pierre Bonnard

, Salvator Rosa

, Gerard ter Borch

, Giovanni Battista Salvi da Sassoferrato

, Maurice Quentin de la Tour

, Joseph Ducreux

, Ron Mueck

, lisabeth Vige-Le Brun

, Sir Henry Raeburn

, Thomas Gainsborough

, George Romney

, Anton Raphael Mengs

, Jacques-Louis David

, Victor Emil Janssen

, Jean Dsir Gustave Courbet

, Georg Friedrich Kersting

, Henry Fuseli

, Francisco Jos de Goya y Lucientes

, Ferdinand Victor Eugne Delacroix

, Jacopo Comin Tintoretto

, Jean Dsir Gustave Courbet

, Jean Dsir Gustave Courbet

, Jean Dsir Gustave Courbet

, Jean Dsir Gustave Courbet

, Jean Dsir Gustave Courbet

, Edvard Munch

, Cristofano Allori

, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

, Max Beckmann

, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

, Egon Schiele

, Frida Kahlo

, Frida Kahlo

, Edvard Munch

, Vincent van Gogh

, Vincent van Gogh

, Vincent van Gogh

, Chuck Close

, Wyndham Lewis

, Henri Matisse

, Cindy Sherman

, Cindy Sherman

, Claude Cahun

,Andy Warhol

, Andy Warhol

, Lucian Freud

, Annibale Carracci

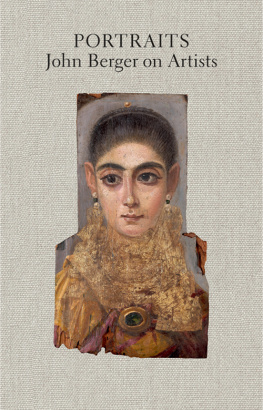

We were created to look at one another, werent we?

Edgar Degas

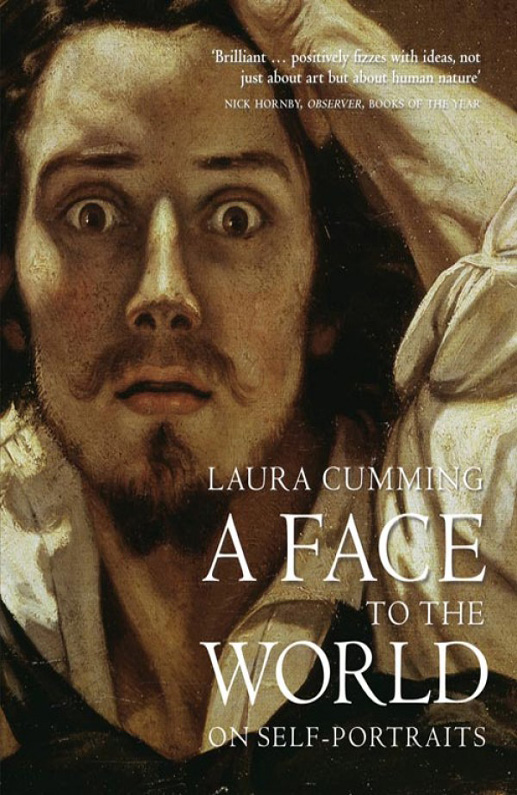

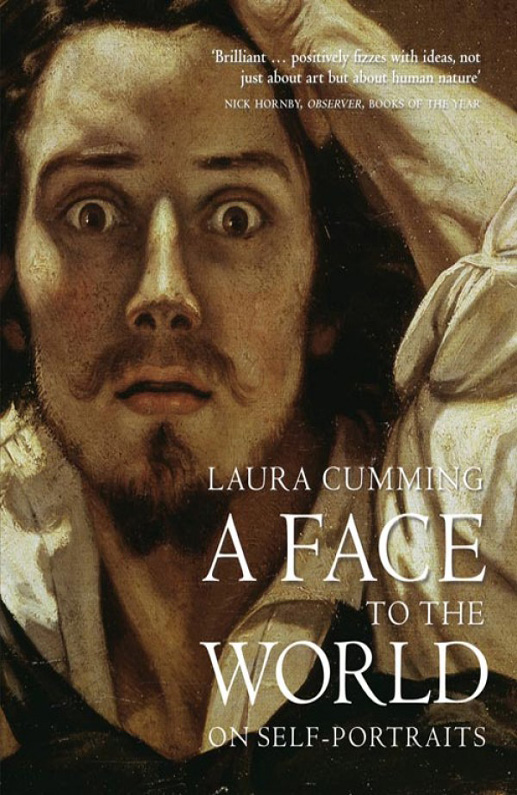

The ideal Shakespeare for Dickens is the Shakespeare we have, a genius and an absolute blank. Immortal, invisible, unimaginably wise: something like God Almighty. This is exactly the comparison that occurs to Jorge Luis Borges in Everything and Nothing, his parable of Shakespeares extraordinary elusiveness as an actual person. Borges imagines a conversation at the pearly gates between the two great creators in which Shakespeare, having been so many other people in his art, appeals to God to let him be just one man at last. But God offers not the slightest hope: I too have no self; I dreamed the world as you dreamed your work, my Shakespeare, and among the shapes of my dream are you, who, like me, are many men and no one. Shakespeare has no unified self, no single identity and certainly no fixed appearance. In fact, he is too great to have been visible at all; Borges describes him as a hallucination, a dream dreamt by nobody, a cloud of ethereal vapour.

For all those who would prefer Shakespeare to remain invisible many more long for a definitive face, perhaps hoping to find a trace of character in its expression, or to feel a direct line of communication opening before them, or just for the simple and irreducible fascination of knowing what Shakespeare looked like. This curiosity is not to be despised. You do not have to believe, like Schopenhauer, that the outer man is a picture of the inner, or that the face is a manifestation of the soul. From the infants ability to read two dots and a dash as primitive features barely before its eyes can focus, to the instinctive imagining of the unseen correspondent or the speaker on the other end of the line, from our mass observation of passers-by in the street to the rage for Facebook, a compulsion to look at our fellow beings unites us. How can one not take an interest in faces, real or represented? It is almost a test of human solidarity.

Yet the strain of antipathy towards portraiture that runs in and out of history, that once demoted it well below battle scenes or bathing nymphs, that derides it as face-painting and mistrusts its version of the truth, has something to do with faces and not just pictures. For faces do not always fit, people do not look as they should. Appearances may create a spurious sense of intimacy when they look right for the part this is just how one imagined the famous person or sudden and dismaying estrangement when they dont. Delacroix, passionate in painting, has a prim little toothbrush moustache. Stravinsky is a lugubrious bureaucrat. Rothko, his aim so spiritual, is a heavy lug in blue-tinted glasses. Almost everyone would prefer a better Shakespeare than the egghead of the First Folio engraving (which Ben Jonson, having known the original, worryingly endorsed on the opposite page) and nobody can stomach the portly dolt with his cushion and quill commemorated in the bust at Stratford. If Shakespeare made us most fully human to ourselves then surely he should look more like some other great soul; Shakespeare should look more like Rembrandt.

Or more like a Rembrandt self-portrait, to be precise; not Rembrandt as he might have looked to a fellow artist. Another painter could have settled a few pedantic questions about Rembrandts actual appearance the colour of his eyes and hair, the shape of his nose and so on about which he is notoriously cavalier and inconsistent. But no matter how accurate such a portrait might have been, it could never give the sense of inner mutability, of a personality altered daily by experience, never fixed, ever-changing, that makes the Rembrandt of the self-portraits so human, so Shakespearean.

Of course it could be argued that self-portraits involve obvious conflicts of interest, that they may be less true to appearances than portraits. But they are not just portraits, for all that art history often treats them as a subset; and they often specialize in other kinds of truth. Artists have portrayed themselves, improbably, as wounded, starving or unconscious beneath a tree, as a baby being born or a severed head dripping blood, as younger or older or even of the opposite sex. We clearly do not consult self-portraits for documentary evidence. But no matter how fanciful, flattering or deceitful the image, it will always reveal something deep and incontrovertible (and distinct from a portrait) namely this special class of truth, this pressure from within that determines what appears as art without, that leaves its trace in every self-portrait. In Rembrandts case it might be the desire to appear head-in-air when most down and out, or the urge to portray oneself as laughing in the dark or all alone in the world. The pose could be an outright lie, for all we know, but the fiction always carries its own truth the truth of how the artist hoped to be seen and known, how he wished to represent (and see) himself. Had Shakespeare been able to paint as he wrote, had Shakespeare left a self-portrait, not even Dickens could have denied its transcendent value.