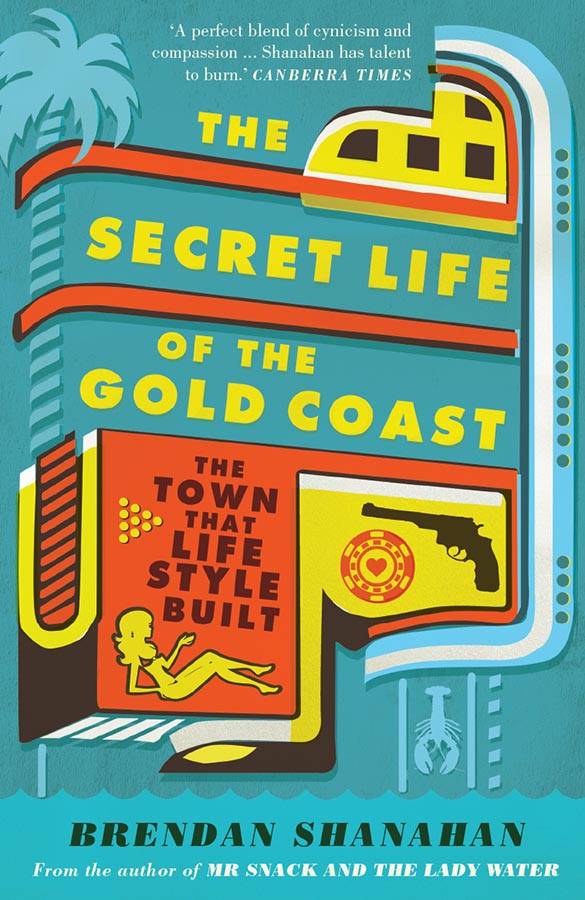

Brendan Shanahan is a writer based in Sydney and Las Vegas. He writes regularly for various publications internationally and is the author of Mr Snack and the Lady Water (2013), The Secret Life of the Gold Coast (2004) and In Turkey I am Beautiful (2008). The latter was described as laugh out loud funny by the Sydney Morning Herald , named one of the best travel books ever by the Sun Herald and listed in the years 10 best non-fiction works by ABC Radio National.

For my mother: whose life-style has always had

a great deal of the former and very little of the latter

Contents

Preface to the 2013 edition

When it was first released in 2004 The Secret Life of the Gold Coast confused a number of people, including my then publishershow else to explain their decision to file it under true crime? To this day I imagine the look on the face of the buyer who picked up my book instead of Chopper Reads How to Shoot Friends and Influence People . The cover, the title: everything seemed to conspire to ensure that the book was met with bemusement, at best. Except in small pockets of southern Queensland where, or so Ive been told, it has something of a cult following

To be fair, it might have been hard to market such an odd book. Is it memoir? Sociology? Travel? Humour? Im not sure that even I know. What it is not, however, despite what a lot of people thought then and now, is a disparagement of the Gold Coast and its citizens. While it is true that the Gold Coast is not a place Im especially fond of, I dont think its any better or worse than any other Australian city, just more a product of its timethe first Australian city of the lifestyle age. The Secret Life of the Gold Coast is less a portrait of a particular place, therefore, than a portrait of Australia and its values at the turn of the new millennium. The Gold Coast embodies a state of mind as much as anything else.

I get little pleasure from reading my own work, especially what I wrote at the age of 25. There are passages Im proud of, but many more that I read, hot-faced through split fingers. In fact, looking through it now, its almost as if had been written by a different person altogether: had I always been such a miserable, moralistic killjoy? Why did something reek of unctuous fetidity when it could have just stank? Apart from anything else, I can barely remember half the scenes I describe. Perhaps Ive tried to erase it all from my memory.

If The Secret Life of the Gold Coast leaves any legacy then it is as a portrait of a period in Australia which will, I believe, come to be seen a turning point: a time when we were on the verge of making more money than at any other, when we were about to enter the war in Iraq, when the first generation that grew up with the internet was coming of age and when lifestyle became not just a marketable commodity but an ideology of sorts. Perhaps in a thousand years someone will discover this book and see in it a record of an extinct era, a time when people were still searching for meaning while unmoored in an amoral wasteland of hyper-capitalism. At the very least, they may get a few good laughs.

Brendan Shanahan, 2013

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the following people for their support: Rachelle and Phil; my journalist friend Amy; Joyce Pallister for help with research; Alexander McRobbie and Paula Stafford for all the historical information; Chloe for suggesting the direction for this book; Annabel and Jeremy for indulging my itinerant habits, and Carrie and Greg for the same. Thanks to Greg Stolz and the Courier Mail for permission to reproduce the story Torture Mistaken for Bondage Ritual on page 12. Thanks also to Mark and Clare and Luke and Pants for rescuing me in Brisbane.

Prologue

INSIDE, THE APARTMENT was like the set of a Beckett play: no furniture, no television, no light globes in their sockets; not a single object that might indicate that this was a place of human habitation. The only visible source of life was a tiny, old-fashioned electrical heater that sat in the middle of the room issuing a low, sinister buzzing noise. Its grubby orange blush crept out to coat the bare, grey surfaces of the room in which the curtains were drawn and everything else was dark.

My friend, a journalist, had arrived to interview a heroin addict who, after having injected a large amount of the drug, drifted off into an opiate slumber on a windowsill eight storeys above the ground. A few minutes later the girl rolled over and fell straight out the window with nothing but concrete paving to break her fall. Thanks to the effects of the drug, she hit the ground as slack as a dead cat and walked out of hospital an hour later with barely a scratch. It was the kind of story the magazine was looking for these days.

The addicts boyfriend led the journalist and the photographer into the kitchen while he disappeared into the bedroom. There were no utensils or food, just a giant pile of clothes, like a termite mound, standing in front of the refrigerator. In the manner of a mountaineer negotiating a precipice, the journalist shuffled past the clothes and was left to stand outside the bedroom door, waiting. From within she could hear the boyfriend attempting to rouse the sleeping girl. He soon reappeared, alone, apologising, before disappearing to try again.

After a matter of some minutes the girl appeared, groggy and listless, her eyes heavy, her jaw set in a slackened death mask. Before the journalist had had a chance to introduce herself, the girl fell over. The boyfriend picked her up off the floor and shook her with urgent reminders that this was the journalist from the womens magazinethe one that had come to do the storythe one who had come to pay her. The boyfriend was keen to reassure the journalist that everything would be all right.

After the second collapse, the journalist disappeared out the door and into the sunshine to call her editors and propose that this story be canned. They agreed and the journalist, trailed by the photographer, made her way across the lawn towards her car. The sight of her leaving was enough to wake the girl from her stupor; she began to scream, staggering her way to the front gate. You fuckin bitch!

The boyfriend too became aggressive, making a lunge for the journalist and forcing the photographer to intervene. The journalist made a run for the car. Together she and the photographer locked the doors and sped away. In the rear-vision mirror they could see the pair running after them with a disjointed junky-jog, shaking their fists and screaming obscenities, like unhappy zombies hungry for a meal of brains.

The journalists name was Liz and she relayed this story to me as we drove. It had happened some months earlier but it had made a big impression upon her, as it did now on me. Up there is where the girl fell out of the building, she told me, pointing to a cluster of towers in the distance. It was my first visit to the Gold Coast and I was seeing the city from what I was to later learn was its most spectacular vantagethe southward approach across the Southport Bridge, the bridge that traverses the Broadwater, the mouth of the Nerang River, and connects the north and south of the city. All around us stood buildingsthey seemed to run forever into the blue haze as we sped along the highway. Tall, white and crystalline, they gathered in apparently arbitrary fungal clumps, as though they had sprouted in the last rain.