ALL THINGS MUST

FIGHT TO LIVE

Stories of War and Deliverance in Congo

Bryan Mealer

Contents

For Ann Marie, my parents, and my sisters

Mealer is a gifted writer who reports his harrowing experiences with humility and humanity.

Greg Houle, African Update

The countrys agonies are far from over, but, in Bryan Mealers new book All Things Must Fight to Live, they now at least have their definitive account It is Mealers gift that even when he is covering what is, journalistically, well-worn territorythe fog of war, the addictive and atrophied life of a combat reporterhis writing is not only fresh but empathetic With the maturity and talent he displays in this book, Mealer could have a dazzling future as a chronicler of distant lands. He has already set a new standard by which all correspondents might approach other forgotten wars.

Time

Gorgeous, heartbreaking, and redemptive. Bryan Mealer has given us a story of a people and a land nearer to our hearts than we know. An immensely honest job of reporting, wonderfully told by a writer who feels as much as he sees.

Robert Kurson, author of Shadow Divers

Vivid prose and compelling emotion [Mealer] recalls the feared Cobra commander of boy soldiers who held sway by the belief in magic, and the soldiers, dressed in wigs and prom gowns, committing unbelievable atrocities. He also reports his own creeping emotional atrophy as he is repulsed and then spellbound by the violence and by the courageous people who struggled to make sense of the fighting.

Booklist

Bryan Mealer has put his life on the line to bring us a story of terror and courage from the heart of Congo. Its already an accomplishment just to go to such a place; to return with such a powerful and important story is rare indeed. Both as a journalist and as a reader, my hats off to Mealer.

Sebastian Junger, author of The Perfect Storm

Goes a long way toward making the phrase dark continent the anachronism that it should be.

Minneapolis City Pages

Mealer spent three years in this shattered land, and his book is a perceptive, empathetic, stomach-twisting presentation of the human condition during chaos Mealers book is a quiet paean to the courage he has witnessed, and its final salute to the many proud people of Congo is as much eulogy as affirmation.

Publishers Weekly

One has to be young and perhaps a touch mad to voluntarily travel, as Bryan Mealer has, by foot, boat, barge, bicycle, rickety airplane, and a train that goes off the rails, through one of the most violent places on earth. But a sane and cautious person would not have been able to bring back the vivid and tragic stories he has, from what is by far the worlds bloodiestand most underreportedzone of conflict.

Adam Hochschild, author of King Leopolds Ghost

Suffer, suffer for world. Amen!

Enjoy for heaven. Amen!

Fela Kuti, Suffering and Smiling

We went in first with soldiers, young and terrified Ugandan kids straight from the villages, whip-thin in their baggy fatigues and wound tight around their triggers even high above the clouds. The Ugandan army flew Antonov-26s into Congo, scrapped by the Soviet bloc and born again for African war, steel Trojan horses loaded with gun-mounted jeeps, barrels of diesel, and crates of banana moonshine. You found a place on the floor and instantly started sweating, nestled between rifles and rocket launchers so close to your eyeballs you could study the paint chips on the grenades. There was little cabin pressure to soothe the landings, and going in fast, you felt like your eyes would pop out of your skull. The soldiers buried their faces in their hats to hide the tears. And all you could do was wince and give a thumbs-up and be thankful the engines were so loud that no one could hear you scream.

Later on it was UN Air, the almighty move-con, sleek, white 727s that floated in like flying nuns. Inside you were greeted by cordial South African blondes who served Coca-Cola and gave quiet comfort to the malaria evac whose IV drip hung from the overhead compartment. You could read a book or fade out with your headphones or lose yourself in the six hundred shades of green below. Coming in was normal enough, but after returning from the field still plugged into the war, stepping into those planes was like being dunked in pure oxygen, or finding your way to the mother ship after crossing a hostile, unsheltered land.

There were eleventh-hour charter flights and Airbus red-eyes, six-seater Cessnas and the French-army Hercules, where female crew members doled out pizza and left you feeling ashamed by your own filth. There were speedboats across the Congo River, old German warships that ferried you over Lake Tanganyika, and one guy I met rode all the way from Paris on a Honda four-stroke before the border guards rolled him clean.

There were journalists and aid workers, diplomats and diamond dealers, assorted opportunists, and third-world peacekeepers deputized and deployed into hell. You could guess the new guys by the way their eyes never left the window; sitting next to them always made me nervous. There were many ways of going in, and everyone had his own reasons. But when we arrived, there was always the same war. Many came simply to test themselves against the brutal country, and Ive learned there is nothing wrong with that. What mattered was what kind of prints you left behind in the red dirt. Five centuries of those bootprints now packed the soil and snaked into the trees, so many they bled into one enormous trail that hid below the camouflage and slowly choked the land.

But get down close and you can see.

One of those trails was mine.

Chapter One

IN THE VALLEY OF THE GUN

I

For me, the war started with the sound of a horn.

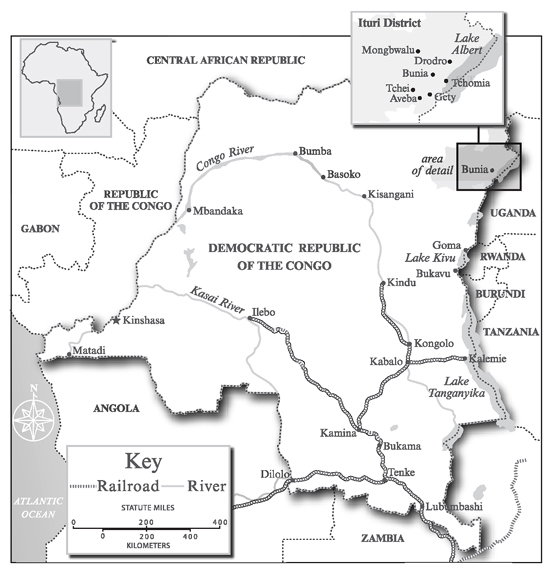

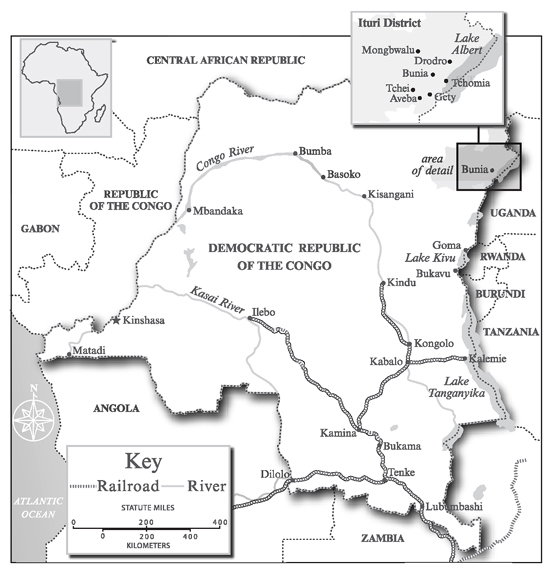

On the morning of April 3,2003, as dawn broke over the green hills of northeastern Congo, several hundred ethnic Lendu warriors gathered along the lip of a narrow valley overlooking the sleeping villages of Drodro, Largu, and Jissa. The villages were mainly occupied by members of the Hema tribe, whod become archenemies of the Lendu in a macabre conflict hatched amid Congos larger, ongoing war, which had swept across the vast nation in 1998 and already killed several million people.

The Lendu fighters carried AK-47s held together with duct tape and wire, rocket-propelled grenades, and mortar tubes strapped to their backs. Some had long spears with steel tips whittled to saw teeth, arrows dipped in poison, and broad machetes ground to a razor edge. Theyd marched all night from their villages deep in the hills, trailing along their women, children, and elderly, who now gathered in the rear and waited for the signal. Finally it came: the low wail of a horn, of a warrior squeezing his air through the narrow bore of a bulls antler. And at the sound of the horn, the bottom dropped from the hills.

They came in three waves: the first rushed in behind a volley of machine-gun fire, rockets, and mortars. The mud-walled huts of the villages exploded and burst into flame as rocket fire and shrapnel ignited the thatched roofs. Villagers scrambled out of their homes and ran for the trees, only to find that every exit was blocked. Gunmen caught them in the open and cut them down with rifles, while others emptied their guns into the thin walls of homes, then torched the roofs.