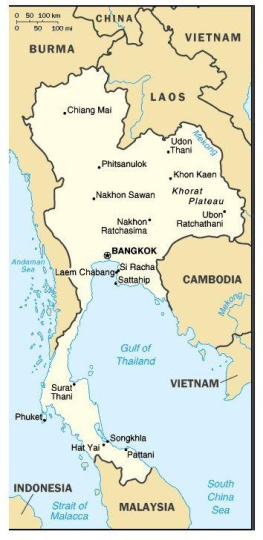

Today, I raced through the streets of Bangkok, Thailand, in my rescue vehicle. I extracted an injured man from a truck at the port, then took him to hospital. Shortly afterward, in another area, I donned a fire suit and breathing apparatus, walked into a flaming building looking for trapped people, and ended up rescuing a fellow firefighter and friend who had fallen. Later in the day, I went to a house to collect a dead body and took it to the local morgue. I will do the same all night, accepting the risks that are ever-present in emergency situations. Ill also expose myself to the added risks that go with doing this kind of work in Bangkok getting attacked by street dogs, arguing with drunks, being confronted by arrogant and ignorant policemen and nurses, the chance of being struck by unconcerned and aggressive motorists at every accident I attend, or even being shot at by crew from a rival ambulance service.

This is a normal day for me in Bangkok. Im not well paid for it. In fact, Im not paid at all. I do what I do for the love of it.

My name is Marko Cunningham, and I am a volunteer for the Ruamkatanyu Foundation, a non-governmental organisation better known as The Bodysnatchers of Bangkok.

Why else do I do it? Well, Im the only farang (Westerner) who does what I do, and not many people can say that of their calling. I appreciate the opportunity to show the Thai people that farang arent all just sex tourists and millionaires. I also enjoy being in the unique position of being able to represent in the media the work of the thousands of volunteers in organisations such as Ruamkatanyu who risk their lives on a daily basis to save others. And lets not deny it: I love the thrill of the work itself. To give with love, as the Dalai Lama once said to me, is the greatest of human actions. And how much greater when the gift you are giving is the gift of a strangers own life?

How did I get into all this? Its a long story, and the story of a spiritual journey as much as a physical one.

This book is not just the story of the life that brought me here. It also takes a look at a side of Thailand that foreigners and many Thais, for that matter rarely or never get to know about. Most would prefer not to know about the underworld of death and disaster beneath the hectic, glossy pace of life in Bangkok.

It also depicts the strange world of Thailands medical system. As far as I am aware, its the only country in the world where volunteers provide this kind of service. The system has its benefits and pitfalls, but it has survived a hundred years or more, and its only getting better.

Some of what I say is brutally honest and very controversial. I know that, in Thailand, I risk my own safety in writing about some of these things. But I am way past caring about my own safety. I face potential death every day and night.

I had my first dream about the tsunami the same night I got back to my apartment in the resort town of Bang Saen. I had fallen deeply asleep, with a bit of help from the bottle of cheap Thai whisky Id polished off, and I dreamed that at some point during the night, there was a knock at my apartment door. When I opened it, I found some members of Ruamkatanyu, the Thai volunteer organisation I belong to, standing there. They explained that the temple in which the bodies of tsunami victims were being kept was full, and they wanted to use my room to store some corpses.

Without a moments hesitation, I said yes. It was simply my duty. I had long since lost my fear of the dead.

My colleagues carried in a couple of the long, white plastic-shrouded bundles that had become so familiar to me and laid them in my room. In the dream, they returned again and again, bringing more bodies each time. I cant remember how often they came, but I do remember worrying that my room was getting full. By the time they left me in peace, there were around 12 or 13 bodies crowding the floor.

I awoke in the morning, sweating, my mouth furry and disgusting, my head pounding. I lay there for a while and stared up at my ceiling, summoning the courage to move and at the same time trying very hard not to think about whisky. Then I suddenly remembered my dream. I lifted my head to look at the floor, and part of me was actually surprised I didnt see bodies there. Its funny: while I knew it was a dream, I still needed to confirm it with my own eyes. Sure enough, there was just my tiled floor, in need of a bit of a sweep, but otherwise clear.

After some time, I heaved my protesting body out of bed and stumbled in the general direction of the toilet. As I blearily rounded the corner, I got a bit of a shock.

My front door was wide open. Outside, the corridor was sprinkled with fine, white sand, and in the sand were the unmistakable outlines of the prints of bare feet, of many shapes and sizes.

I dont believe in ghosts. I used to be a sleepwalker when I was a kid, and its happened a few times since Ive been an adult, when Ive been worse for wear from drink. I presume that, in my drunken state, I must have sleepwalked to the door and left it open. People returning from a stroll on the beach must have peeked in to have a squiz at the drunken, snoring farang.

Thats my perfectly rational, farang explanation for it. But when I tell Thai friends this story, they shrug and offer a perfectly simple explanation of their own from Thai culture. The ghosts of people whose lives had been cut short by the tsunami had become trapped in our world and found themselves unable to find their way home. They had seen me taking care of the dead and had decided to follow me to ask for my help. And because I had opened my door to them that night in my dream, I had let the ghosts into my room and, by implication, into my life. My friends had no doubt that I now had a dozen or so ghosts of tsunami victims following me around.

Yeah, right, I answered. For how long?

The rest of your life, they said. To be freed from them, I would have to go back to Wat Bang Muang in Phang-Na province, the temple-turned-mortuary where I had worked in the aftermath of the disaster. I would need to ask the monk there to perform a ceremony to separate the ghosts from me and release them from this earth.

I never did it, because I dont believe in ghosts. My Thai friends unanimously believe I still sleep with the dead in spirit, just as I had actually slept in the company of corpses in the refrigerated containers in the tsunami-stricken region of southern Thailand. Some of them wont go to sleep in the same room as me, because while they have no objection to sharing a room with me, theyre not so keen on sleeping with a bunch of ghosts.

That was the first dream. Others followed. One night, I woke up convinced someone or something had been trying to strangle me. I sat up gasping and holding my throat as if something had just been squeezing it with strong, icy fingers. This time, there was no sense that it had been a dream. It felt as though it had really happened, and I was a little freaked out by it.

Googling and asking around, I discovered a rational explanation for this one, too. Apparently, dreams of drowning or choking are common among people experiencing stress. That was surely the answer. Still, it gives me a bit of a chill whenever I think about it. It was amazingly real.

Occasionally, I dreamed I was searching for the dead. I knew they were waiting for me, and I had to find them. In one dream, I was searching the seabed for them, pulling bodies free of the silt and bringing them up to the surface. I knew they were happy once I had found them, so I dived again and again, without any air tanks, just holding my breath. This dream, too, ended with me waking gasping for breath, as if Id just been deep underwater.