One of my earliest memories of Peter Scott is when he invited me to open the Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust on the Severn estuary. After an extensive and intensive tour of the, at that stage, potential facilities, we repaired to lunch at the small cottage where he and Philippa were living at the time. Somewhat to my surprise, a roast duck was produced and, sensing that there was some hesitation about who was to carve it, I offered my services.

Peter Scott had achieved world fame by the time he became one of the founders of the World Wildlife Fund, and he recruited me as a Trustee. I attended as many meetings of the trustees as I could, and I always tried to sit next to Peter because he had a habit of doodling throughout the meeting on any bit of scrap paper available. Some of these masterpieces are now framed and on display at Sandringham.

I think that his most apparent characteristic was his utter dedication to the conservation of wildlife and wild places of all kinds. He endured the inevitable committee work, but his heart was always in the wilderness, and his passion was to ensure that it survived for future generations to admire and enjoy. This collection of his writings is ample proof of a lifetime spent in the single-minded pursuit of effective and adequate protection for the wildlife and wild places of this limited planet.

by Martin Spray CBE, Chief Executive of WWT

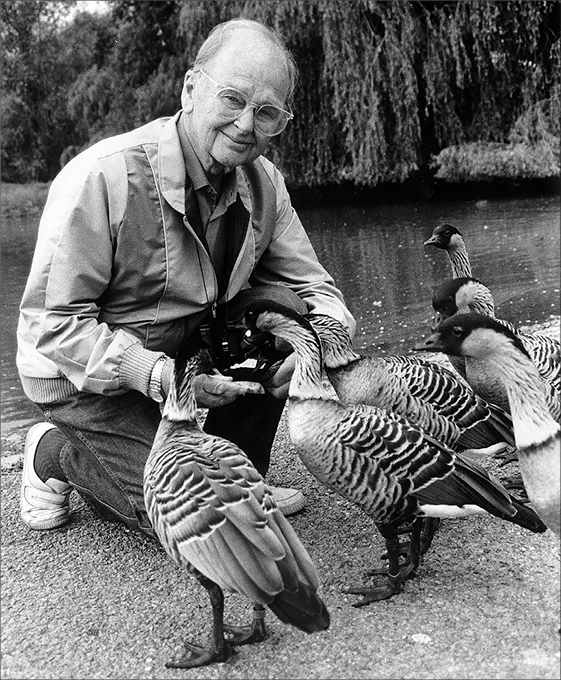

Great and lasting achievements are usually brought about by individual vision matched with talent, and the drive and determination to achieve. Sir Peter Scott had all these attributes and in quantities beyond the comprehension of most of us.

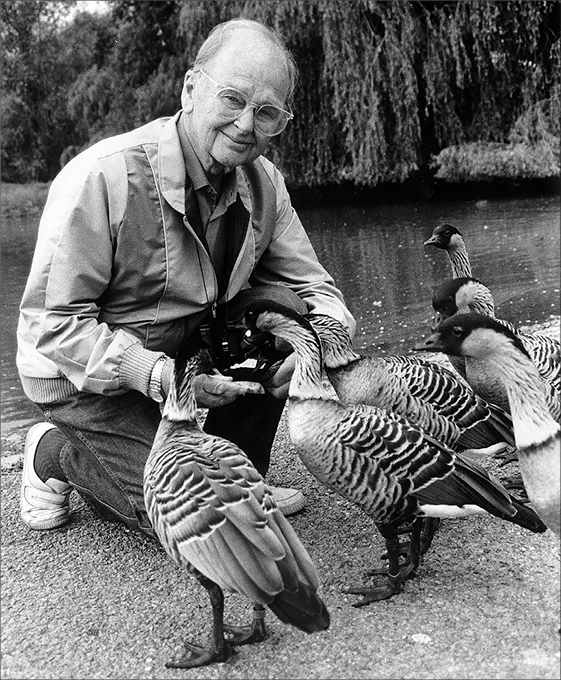

He was an accomplished artist, a gifted communicator and writer, one of the first natural history broadcasters, a champion skater, a world-class glider pilot and an Olympic yachtsman. Above all Peter Scott was, without doubt, one of the most visionary and influential conservationists of his generation and the architect of modern conservation.

Peter, through his passionate interest in nature, and especially wildfowl, saw what was happening to the world and was determined to do something about it. But his vision went further. He recognised then, nearly 70 years ago, something that the modern conservation movement now puts at the centre of its action. Unless we inspire, interest and educate people about nature and its relevance and importance to our lives, it will not be valued and our attempts to conserve it for future generations will fail. He set out on this mission with drive and determination which surpassed even the extraordinary achievements of his parents, with a talent for communicating and engaging people, and with the vision necessary to make a huge difference.

Among his many gifts and achievements, Peter was a prolific and accomplished communicator. This selection of his various writings is extraordinary in the way each brings to life the story, the place and his feelings and thoughts so vividly and engagingly. Reading them, you can almost hear him speaking to you personally. Just one example for me is a portrayal of the sound of geese callinga music of indescribable beauty and wildness, a harmony with the flat marsh which is their home. It was this gift of being able to convey serious science, combined with passion and emotion, that I am sure enabled him to reach out to so many people and to achieve the considerable advances in conservation he achieved during his life.

These writings give a real insight into the development of Peter's thinking. His curiosity and endless thirst to know and understand more stand out, together with his personal connection with and love of the natural world. He was an internationalist, multi-talented, a man with a powerful mission. We are very fortunate, through this collection of his writings, to be able to experience the thoughts and passions of a man who loved life, lived it to the full, and made a real and lasting difference to the world we know today.

by Paul Walkden

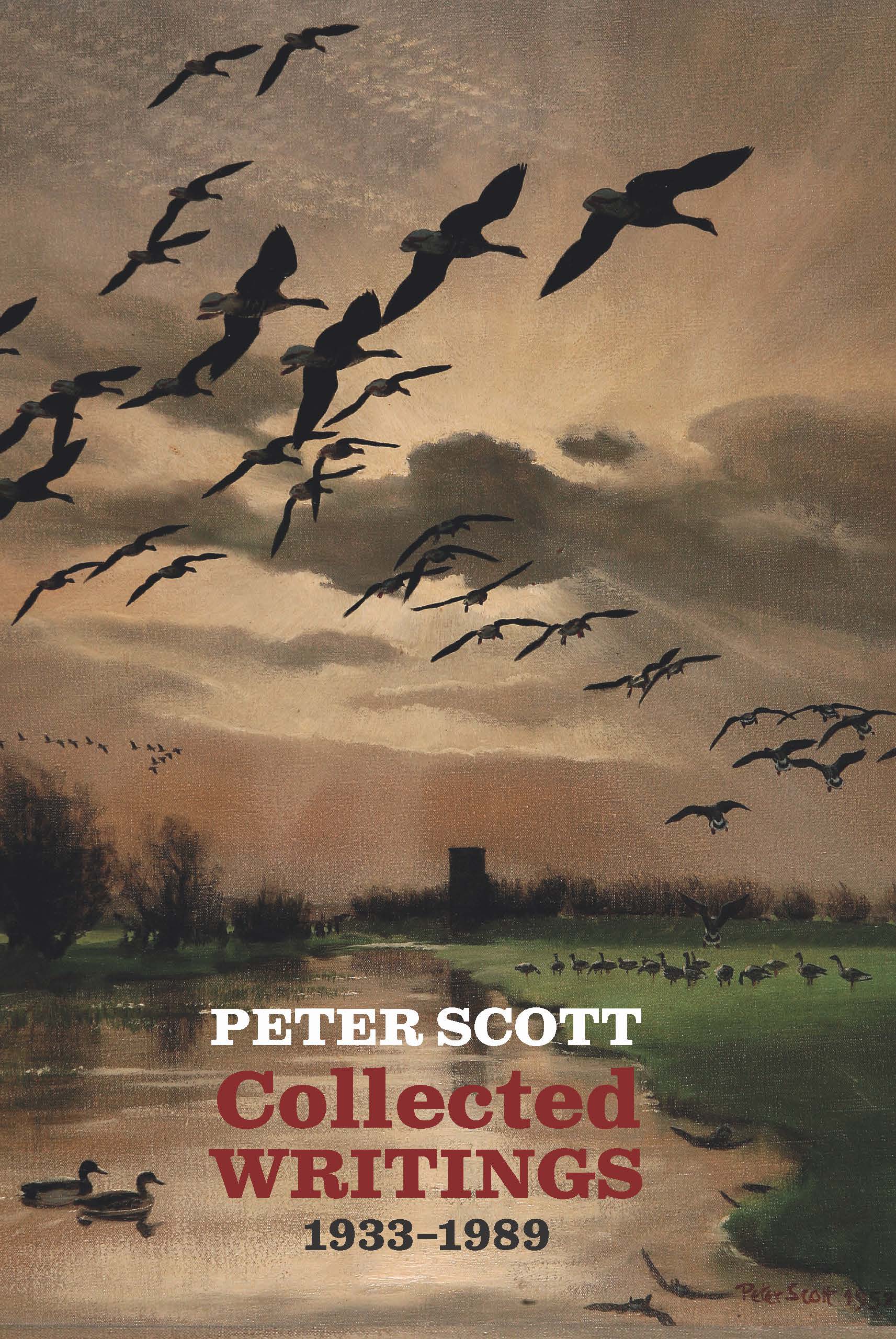

Peter Scott was one of the first leaders of the conservation movement and an outstanding communicator. This book arose from my interactions with him over an extended period, and more recently from discussions between myself, Barbara Cooper, who has edited this compilation, and Paul Harding, who has designed and produced it. It was felt that Peter Scotts legacy should continue to be shared with all those interested in conservation. During my research as Scotts bibliographer, I have found many of his less well known writings such as magazine articles, speeches, diary entries and broadcasts, and the ones chosen here reflect the many spheres in which he was involved.

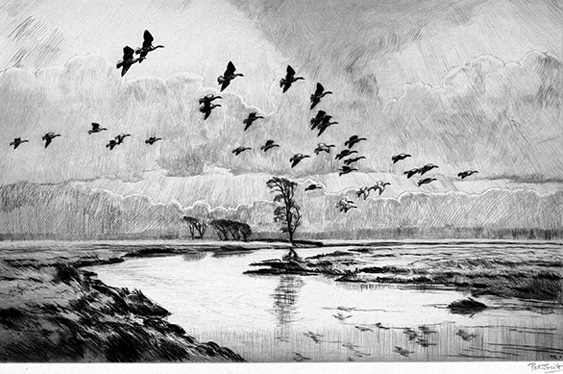

I was very fortunate to have known Peter personally, an exceptionally kind man who encouraged and helped people in whatever way he could. To me he offered much help and time in putting together his bibliography. We met and discussed books on various occasions, his library an important source of information for me; he was always very generous in loaning books. He had a real passion for whatever he was working on at the time and he loved sharing his thoughts and ideas. I was privileged to have sat and discussed the new Slimbridge centre project being planned shortly before he died, including his ideas for a Tower allowing all people, including the disabled, to be able to look out over the River Severn from the centre. I also enjoyed watching him paint at the easel or sketching whilst we talked. His artwork was always immediate and fresh, living and vibrant. His final exhibition was held at Ackermanns gallery in Bond Street London in March 1989 which was opened by HRH The Duke of Edinburgh and was a sell-out. At that time Peter wrote: I have been excited by wildfowl for most of my life and have been painting them and the wild areas they live in for more than sixty years. Wildness is the aspect that specially appeals to me. I believe Thoreau was right when he wrote In wildness is the preservation of the world. He was ahead of his time.

From Morning Flight (Country Life, 1935)

There is a peculiar aura that surrounds in my mind anything and everything to do with wild geese. That I am not alone in this strange madness, I am sure: indeed, it is a catching complaint, and I hardly know any who have been able to resist its ravages, when once they have been exposed to infection. It is difficult to know just why this should be so. It is perhaps a matter both of quality and quantity.

I wish it were possible accurately to estimate numbers after they have reached the thousands.