Copyright 2014 by Richard Gilbert

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper).

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper).

Michigan State University Press

East Lansing, Michigan 48823-5245

Printed and bound in the United States of America.

20 19 18 17 16 15 14 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Gilbert, Richard, 1955

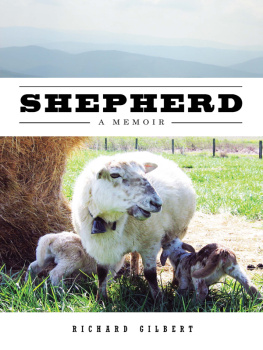

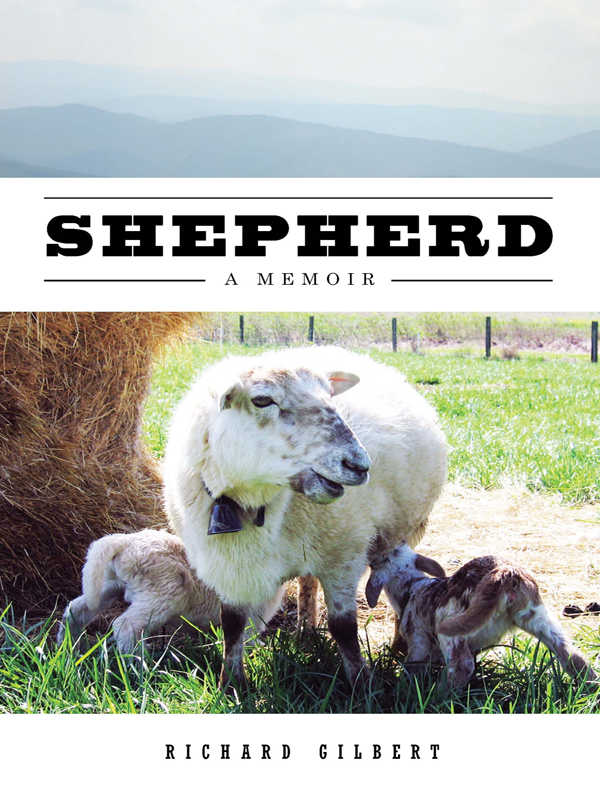

Shepherd : a memoir / Richard Gilbert.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-61186-117-4 (pbk. : alk. paper)ISBN 978-1-60917-407-1 (ebook) 1. Gilbert, Richard, 1955 2. Sheep ranchersOhioBiography. 3. Sheep farmingOhio. 4. Family farmsOhio. I. Title.

SF375.32.G54A3 2014

636.3'1092dc23 [B] 2013025307

Book design by Scribe Inc. (www.scribenet.com)

Cover design by Shaun Allshouse, www.shaunallshouse.com

Cover image is of Freckles and two of her lambs, and is used courtesy of Richard Gilbert.

Michigan State University Press is a member of the Green Press Initiative and is committed to developing and encouraging ecologically responsible publishing practices. For more information about the Green Press Initiative and the use of recycled paper in book publishing, please visit www.greenpressinitiative.org.

Michigan State University Press is a member of the Green Press Initiative and is committed to developing and encouraging ecologically responsible publishing practices. For more information about the Green Press Initiative and the use of recycled paper in book publishing, please visit www.greenpressinitiative.org.

Visit Michigan State University Press at www.msupress.org

ISBN 978-1-62895-013-7 (ePub)

ISBN 978-1-62896-013-6 (Kindle)

For Kathy, Claire, and Tom

And to the memory of my parents:

Charles Churchill Gilbert

Rozelle Rounsaville Gilbert

What tickles the corn to laugh out loud, and by what

star to steer the plough, and how to train the vine to elms,

good management of flocks and herds, the expertise bees need

to thrivemy lord, Maecenas, such are the makings of the song

I take upon myself to sing.

from Georgics, Virgil (Peter Fallon trans.)

PROLOGUE

CHILDHOOD DREAMS CAST LONG SHADOWS INTO A LIFE. AS IF THE strong feelings they stir prove their validity, dreams propel the dreamer through an indifferent world. Which explains how I, a guy who grew up in a Florida beach town, find myself crouched beside a suffering sheep in an Appalachian pasture.

Richard, I think you should call the vet, says my wife. Kathy and I flank the ewe's prostrate body.

Our third lambing has just begun this spring of 2001, and Red is in trouble. I'd found the little ewe in distress and had urged her up and nudged her inside an old shed, where she'd collapsed and resumed straining, panting as if in labor. But nothing happens; no lambs, hour after hour.

Kathy knows I'm reluctant to seek paid help. We're on a tight budget and I'm trying to be a practical farmer, even if still part-time: commercial shepherds do their own veterinary work, or they simply shoot and compost ailing ewes. Profit margins, razor thin, can't support farm calls.

But Red, small and fine-boned, white with a roan patch on her neck, is a special case. She emerged four years ago from the anonymity of our new flock, fifteen rambunctious ewe lambs, by insisting on making herself our pet, surprising us and astonishing her wild flockmates. During a disastrous renovation of our farmhouse that summerwe maxed out our credit cards, spent our kids' college savings, and borrowed against our retirementaccountsshe'd sidle up every afternoon to be petted. As our other sheep stared at her in wide-eyed horror, Red mooned up at us with trusting eyes, charming us and lightening our cares.

So I relent and call Maggie Swenson this Sunday afternoon. She arrives as heavy shadows from hickory and locust trees fall across the pasture. Maggie announces after a quick check that Red's cervix isn't dilated, and then she sits back with a puzzled frown on her elfin face. Red sure appears to be in labor. I mention ringwomb, when a pregnant ewe comes to full term yet fails to dilate for delivery, which I've heard about in an e-mail listserv for shepherds.

Could be, Maggie says doubtfully, her short gray hair luminous in the shed's deepening gloom. I wonder if ringwomb is even a recognized sheep ailmentthere are so many, and I can't find it in my reference booksor just more gossip from my virtual colleagues, who keep me fretting about the endless woes that sheep are heir to.

Should we load her up and bring her in? I ask.

I don't see what good it'll do to bring her in.

Maggie seems to be writing Red off, though she's too kind to say anything so harsh, and her attitude puzzles me as much as Red's condition does. Where's the help I'm paying for? If she hasn't delivered by tomorrow, I say, maybe I should bring her in for a C-section.

Maggie nods. Call first, she says. Then she shows us how to massage Red's cervix, which Kathy does for an hour without result, and we return to our house and our children in the mild April darkness.

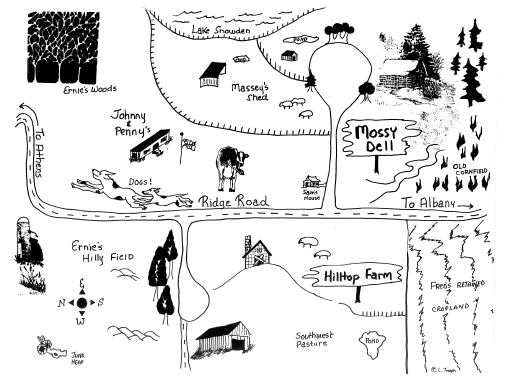

My father lost our farm in Georgia when I was six, and I grew up in Florida fantasizing about reclaiming our land. Decades later, when Kathy's job took us here, to a place where we could buy a working farm, my boyhood dream resurfaced and carried me away.

I'd said I wanted an adventure when we moved to this beautiful backwater, Appalachian Ohio, from our comfy house in prosperous suburban Indiana, yet the first thing I learned was that I didn't like starting over in a new place; it was hard, and didn't suit my need for stability. As a local acquaintance jokes about such matters, It weren't easy. In early middleage, Kathy and I had returned to Ohio with two young childrennot to the state's busy capital where we'd met in graduate school fifteen years before, but to Athens, a battered brick enclave in the state's remote southeastern corner. We were shocked. Athens seemed to have more in common with a village in dusty western Kansas than it did with long-domesticated Ohio, a state of orderly farms, dotted with big industrial cities. Just before moving I had learned that Ohio had an Appalachian region, and upon arrival saw what that meant: poor, tired towns; roadsides choked with litter; the land abused for decades by extractive industriescoal mining, timber cutting, natural gas drilling; the growing of erosive row crops like corn. I was horrified that we'd traded our stable, affluent world for this pinched place.

We'd moved only six hours east from Indiana, but had come so far. We couldn't know how far we had to go. We hadn't expected to find such stark regional differences. We'd accepted the myth that America has been homogenized, scrubbed clean of warty local distinctions by affluence, by shared television shows, and by broadcasters whose bland voices erode the patterns of proudly regional speech. Part of me was thrilled to discover there are still places in America, and for all its poverty and isolation it was the most beautiful landscape I'd ever seen. In Ohio's hill country, a wrinkled shirttail dangling untucked above West Virginia, everything felt different: the layered woods, the light flashing off pebbled creeks, the wind in the trees, the wild phlox that bloomed pink beside shaded roadsides late in May.

All we needed to make my dream come true, I'd vowed to myself after our exhausting relocation, was our own land. I pictured cattle lowing across a drowsy green valley in the sun-heavy afternoon, a red banty hen clucking in the barnyard dust. What I hadn't known as a daydreaming kid in Florida, and couldn't foresee as a neophyte agrarian in Athens buying land and livestock, was that my Eden could be so very complicated. All I knew, though I wasn't sure why, was that I had to act on my desire at last.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper).

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper).

Michigan State University Press is a member of the Green Press Initiative and is committed to developing and encouraging ecologically responsible publishing practices. For more information about the Green Press Initiative and the use of recycled paper in book publishing, please visit www.greenpressinitiative.org.

Michigan State University Press is a member of the Green Press Initiative and is committed to developing and encouraging ecologically responsible publishing practices. For more information about the Green Press Initiative and the use of recycled paper in book publishing, please visit www.greenpressinitiative.org.