GILBERT WHITE

Richard Mabey has been described by The Times as Britains foremost nature writer. He is the author of Flora Britannica, which was the winner of the British Book Awards Illustrated Book of the Year, and the Botanical Society of the British Isles Presidents Award. His biography of Gilbert White won the Whitbread Biography Award in 1986, and his memoir Nature Cure was shortlisted for the same prize in 2005.

Richard Mabeys other books include Food for Free, The Common Ground, Whistling in the Dark (a personal study of the nightingale), The Frampton Flora and Home Country. He is a regular broadcaster and contributor to The Times, Guardian and Granta.

After spending most of his life in the Chilterns, he now lives in Norfolk, where he is President of the Norfolk and Norwich Naturalists Society.

This edition published in Great Britain in 2006 by

PROFILE BOOKS LTD

3 A Exmouth House

Pine Street

London EC1R 0JH

www.profilebooks.com

First published in Great Britain in by

Century Hutchinson Ltd 1986

Pimlico edition 1999

Copyright Richard Mabey 1986, 2006

3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4

Printed and bound by

CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CRO 4YY

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN-10: 1 86197 807 3

ISBN-13: 978 1 86197 807 3

To Ronald Blythe and Charles Clark

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My thanks for help in locating, viewing and interpreting source material to: the Bodleian Library, Oxford; June Chatfield and the Gilbert White Museum, Selborne; the Hampshire Record Office; the Hertfordshire County Library Service; Melanie Wisner and the Houghton Library, Harvard University; Oriel College Library, Oxford; Mrs Parry-Jones and Magdalen College Archives, Oxford; and Ian Lyle, Librarian of the Royal College of Surgeons, in whose keeping the working manuscript of the Natural History is currently resting.

Thanks also to those who helped with ideas, information and guidance during the preparation of the text: David Elliston Allen; Tara Heinemann; Chris Mead of the British Trust for Ornithology; Richard North; Max Nicholson; Philip Oswald; David Standing, curator of the Wakes garden; and Dafydd Stephens. A special thank you to Anne Mallinson of the Selborne Bookshop, who was an unfailing source of support, contacts and local information.

I am grateful to the Leverhulme Trust for a research award that greatly facilitated my work in Oxford and Selborne, and to Wilfrid Knapp and the Fellows of St Catherines College, Oxford, for their hospitality. Vicky and Ian Thomson were also generous with hospitality in Hampshire.

Sandra Raphael, Francesca Greenoak, Richard Simon and Isabella Forbes made valuable comments on various drafts. My assistant, Robin McIntosh, worked tirelessly, as usual, especially in the final stages.

Finally, I must express my warmest gratitude to Charles Clark, for suggesting that I write this biography in the first instance, and for his support and faith during its protracted progress; and to Ronald Blythe, whose advice, example and encouragement were a constant inspiration.

ILLUSTRATIONS

(Between pages 114 and 115)

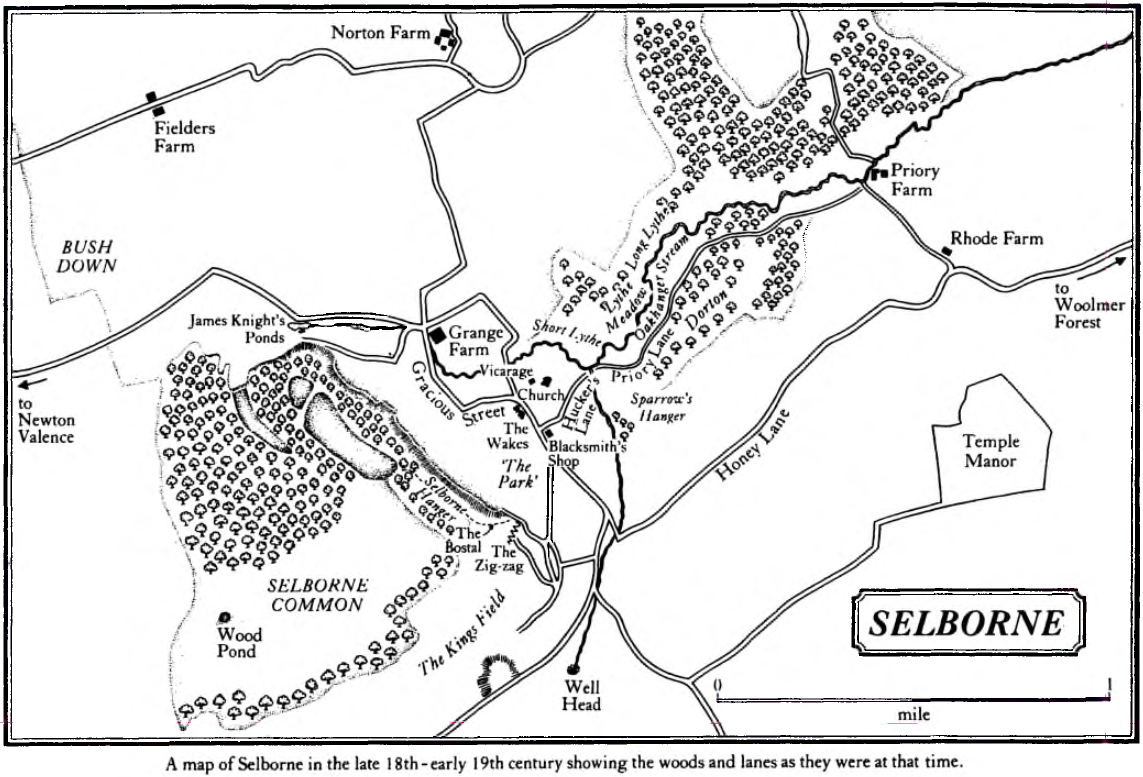

A view of the Hanger from the Lythes in the north-east.

(Houghton Library, Harvard University) |

| John White, born 1727 |

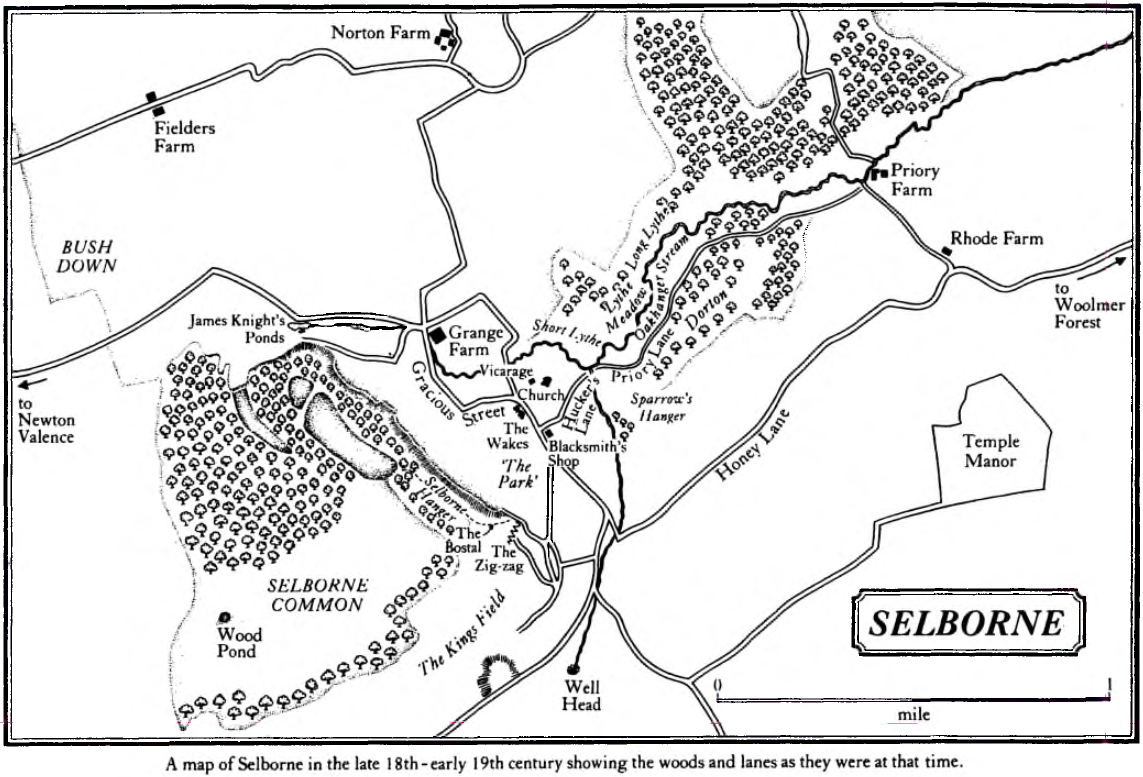

The Short Lythe and Dorton from Huckers Lane

(Houghton Library, Harvard University) |

| A more decorous view of Dorton and the Lythes |

Selbornes stream in Silkwood Vale

(Houghton Library, Harvard University) |

| The old hollow lane to Alton |

| Thomas White, born 1724 |

| Mary White, born 1759 |

| Rebecca Snooke |

A view of the Wakes from the foot of the Hanger in the 1770s

(Houghton Library, Harvard University) |

| A closer view of the Wakes, circa 1875 |

The old Hermitage on the Hanger

(Houghton Library, Harvard University) |

| Henry White in later life |

| Catharine Battie |

View of Selborne from inside the Hermitage

(Houghton Library, Harvard University) |

| A view from higher up the Hanger |

Selborne church from the churchyard

(Houghton Library, Harvard University) |

The Plestor at the church end of the village street

(Houghton Library, Harvard University) |

The language of birds is very ancient, and, like other ancient modes of speech, very elliptical: little is said, but much is meant and understood.

Gilbert White, Letter XLIII to Daines Barrington,

9 September 1778

GILBERT WHITE

Legacies and Legends

The British have for a long time regarded their relationship with the countryside as something quite distinctive, a badge of cultural identity. Despite having become a largely urban people, we continue to admire the rural village as the idea form of community, and have an affection for the native that is probably without parallel in the industrialized world. It is a passion which has sometimes deteriorated into sentimentality, and which doesnt always have a very clear view of history, but it has left an indelible mark on our way of life. And standing as its principal text, as the first book to link the worlds of nature and the village, is Gilbert Whites The Natural History of Selborne. This deceptively simple and unpretentious account of natural comings and goings in an eighteenth-century Hampshire parish has come to be regarded as one of the most perfectly realized celebrations of nature in the English language. The American writer J.R. Lowell once described it as the journal of Adam in Paradise. This was extravagant even by the generous standards of the tributes heaped upon this book, yet Lowel had succeeded in catching something essential about both the man and his writing. Selborne, the real English village that is the setting for the book, may fall a mite short as a model for paradise; but the dramas of courtship, birth, survival and migration that are played out in its woods and fields, have, as recounted by White, something almost sacramental about them, Although he lived at a time when the rule of reason and the supremacy of man were accepted almost as gospel, White contrived to portray the daily business of lesser creatures as a source not just of interest, but of delight and inspiration. To that extent the book is a glimpse of a place of sanctuary.

What is extraordinary, given the books originality and importance, is how little is known about its author. To cast him as Adam, as Lowell did, is an example of the way his life and character have been repeatedly idealized, as if knowing too much about him might break the spell. This is a common enough process with national heroes, and is arguably a perfectly sufficient reason for a biography. Yet it is as well to make clear that I had an additional motive in beginning this study. Not long after discovering White, I began to be struck by what a modern figure he was; by the way that many of his attitudes and problems for instance, how to reconcile a love for nature with an enjoyment of the stimulation of urban life had recognizable parallels today; and most strongly, by how the facts of his protracted, compromised but ultimately triumphant resolution of these difficulties shone through the sentimental mists with which we shroud so much of our rural past, as a heartening and exemplary story.