I was born Richard and spent most of my life as Richard and Marjorie. No question, the better half made the other half a whole lot better.

I didnt then, but now they will know what I did when I did.

And Adam. Truly, number one son.

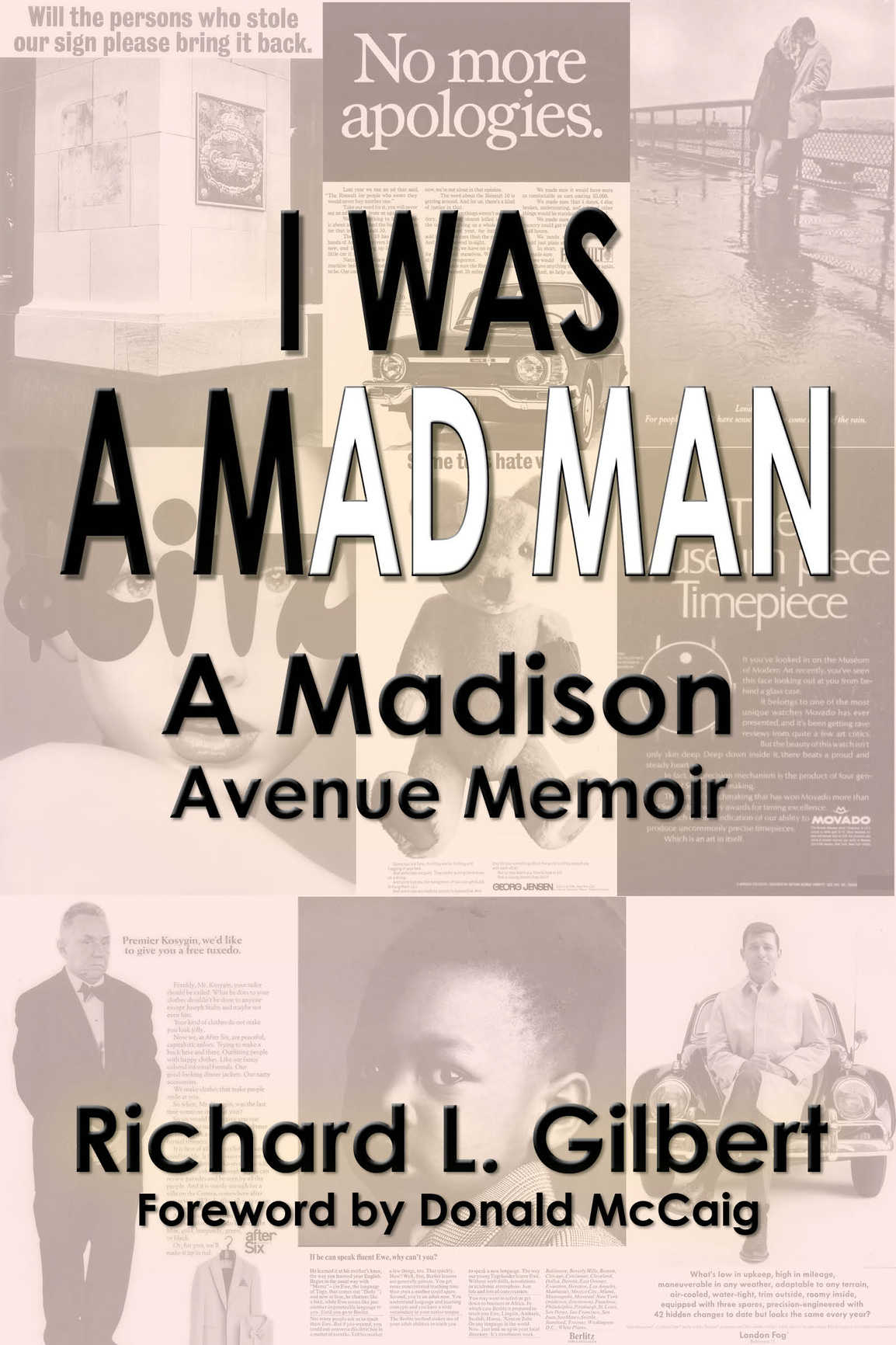

Introduction by Donald McCaig

Introduction by Donald McCaig

I dont know why Richard Gilbert hired me. My wife and I were separated, and I was sleeping in flophouses or on friends couches. I remember one apartment above a Hells Kitchen Irish Saloon where every weekend the floor would bounce to The Rising of the Moon.

Mr. G was a fastidious, stylish dresser, and I never saw him without a jacket. I didnt own one.

Mr. G was a New Deal Democratic liberal who turned down cigarette accounts and sometimes spoke about business ethics. Several of my SDS friends faces adorned post office walls. In my guilty heart, I sometimes believed I should be up there with them.

It wasnt as if I could get lost in the Gilbert crowd: the creative department was a half dozen art directors and copywriters, and it was a family shop. Charlie, the production manager, Bess the office manager and Mike Greenberger, the Account Exec, were all close to Mr. G.

The reception area was tasteful but by hot shop standards, unglamorous; Barcelona chairs, round glass coffee table, secretaries took turns on the desk/switchboard. Lining one wall were the crown jewels: iconic, astonishing ads. I studied them while waiting for my job interview. It was hard to believe one tiny agency had produced so many legendary ads.

Richard describes those ads so I wont. They were written when print was more important than it is today and Time, Life and Newsweek were rich and thick with tobacco and brown whiskey ads.

This spring I was dining with Noah Adams and Neenah Ellis and told them about writing this introduction. Noah asked: What ads did you do?

My friends remembered ads which appeared once nearly forty years ago. Gilbert ads were as good as American print advertising ever got.

Mr. G hired me and paid me more money than Ive earned since. I didnt have a checking account so paydays Id take my check to the bank for cash.

One afternoon, Jorgen Jenk, Georg Jensens CEO, invited us creative types to luncheon at Jensens suburban headquarters. It was my first limo ride and the only time Ive drunk fine wines from crystal goblets almost too heavy to lift. I accepted the challenge and on the woozy drive back to Manhattan decided that it would be neat to be rich; a view circumstances subsequently modified.

Manhattan in the late 60s was the best and worst of times: Maxwells Kansas City, happenings, Hair, Bring the War Home, Bobby Kennedy, the Velvet Underground, The East Village Other, Norman Mailer, Yippies, Martin Luther King, twenty dollar ounces, fifty cent cigarettes and beer, Allan Ginsberg, The Mobe, The Black Panthers, The Central Park Be-In, The White Album, Nashville Skyline, The Band

When Dick Levy and I showed Jorgen Jenk his new Georg Jensen campaign, Jorgen flipped through the layouts once, read the text once and approved them. First and only time that happened in my brief advertising career.

John Bernbach, our account exec took Some Toys Hate War to Georg Jensen the Friday night before a huge DC antiwar demonstration. Nobody knew what might happen on Sunday when the ad would appear in The Times. Would demonstrators be fired upon, would they charge the White House? The ad ran.

Gilbert Advertising was a rare work place. All I was ever asked for was my best work while Mr. G took the big chances with his business, his reputation, and his (extended) families livelihoods.

Later on I got my own apartment around the corner from the Fillmore East. After work, Id come home, smoke a joint, put Japanese flute jazz on the stereo, sit on the floor, and write poetry. Sometimes Id write advertising copy.

Didnt seem so different at the time.

Donald McCaigs books have been translated into 11 languages.

1 Stepping to the Plate

1

Stepping to the Plate

Play Ball

Summer 1950. No one would call a colored (not yet African-American) ballplayer and a rookie adman the ideal double-play combination. Even if the ballplayer was Jackie Robinson.

The adman? On Wednesday, May 24 of that mid-century year with no clients, some freelance assignments, no gray flannel suits, $3,500 in Army terminal leave pay, and notes of cheer from well-wishers including a former employer and his rooster, more of whom later, I started Gilbert Advertising.

Think of this. No computers: only typewriters and calculators. Carbon paper, not printers. Emailwhats that? No Internet. Little commercial television. Print and AM radio the dominant media. FM only experimental. Your pencil was your valued partner, along with courage and imagination.

For a period after my Army discharge, I tried publicity, sold radio time, and worked as a copywriter. Advertising had a seductive lure. I was comfortable with my skills and just decided to jump in. The industrys ethnic barriers and shallow mainstream limited a newcomers access to established firms. The easiest door to open was my own.

I didnt know it at the time, but that humble, post-World-War-II beginning enrolled me in one of the great entrepreneurial surges on record. Millions of us switched uniforms for pinstripes, started businesses, expanded the playing field, and set the stage for a period of growth and social change unmatched in American history.

Talk about humble beginnings. I signed a short-term lease, a scary obligation, for a V-shaped corner on the twenty-sixth floor of 101 West 31st Street. Open a window and tissue layouts became model airplanes. There were three desks, a secretary, a part time art assistant, a part time production man, and a water cooler we shared with others on the floor. Dick Janover, my dads accountant and a friend, stood watch over the modest numbers.

Our windy warren was blocks west of Madison Avenue. We looked down a busy Sixth Avenue of fur and flower districts, pavement gardens and rolling pushcarts. Traffic staggered in the traditional two-way pattern. In the mid-fifties, Commissioner T. T. Wiley, anticipating future gridlock, dramatically modernized the citys thoroughfares by installing one-way directions with timed signals, amber lights, and computerized controls. Commissioner Harold Barnes carried his work forward, and in 1965 Fifth Avenue was the last boulevard to fall in line. (Hard to believe there was a time when patrolmen directed vehicular traffic in elevated signaling sheds, twelve feet above the famous roadway.)