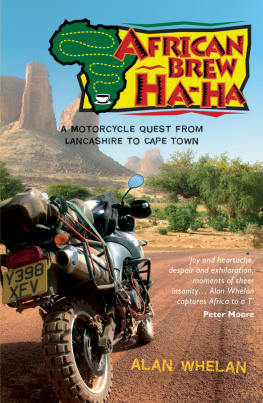

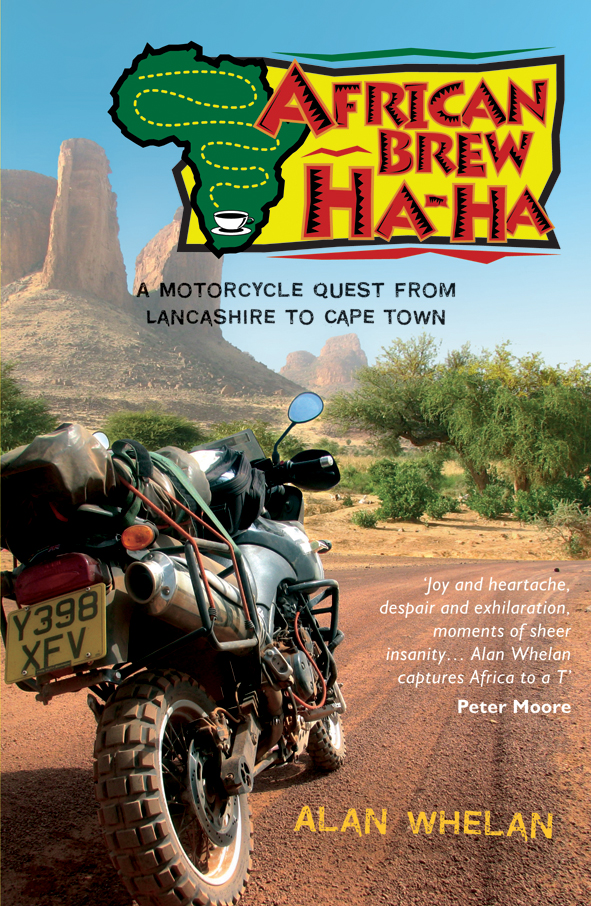

AFRICAN

BREW

HA-HA

A MOTORCYCLE QUEST FROM

LANCASHIRE TO CAPE TOWN

ALAN WHELAN

AFRICAN BREW HA-HA

Copyright Alan Whelan 2010

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced by any means, nor transmitted, nor translated into a machine language, without the written permission of the publishers.

The right of Alan Whelan to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Condition of Sale

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publisher.

Summersdale Publishers Ltd

46 West Street

Chichester

West Sussex

PO19 1RP

UK

www.summersdale.com

Printed and bound in Great Britain

eISBN: 9780857653086

Substantial discounts on bulk quantities of Summersdale books are available to corporations, professional associations and other organisations. For details contact Summersdale Publishers by telephone: +44 (0) 1243 771107, fax: +44 (0) 1243 786300 or email: .

For Olive, with love

Contents

1

HELLO THERE

Right, lets have tea.

Margaret Francis

The wonder, and perhaps a little envy, on the faces of the businessmen on the forecourt of the motorway services coming in out of the rain confirms how I must look to others. Im certainly not going to work. These besuited Audi drivers who already look foreign to my eyes get a fleeting glimpse of a life about to be lived; a fleeting, imaginary escape from the quotidian.

Im drenched through so I have a warming cup of vending-machine tea in a privately ironic nod to my immediate future, and as a souvenir I leave a puddle on the floor of the service station.

I get back on the Triumph and gingerly ease my way out of the services onto the M6. Unused to the immense weight of the luggage on the bike, I squirm between the lanes of motorway traffic. I have so little control I feel more like a passenger. Despite battling with the steering, the amazing, mind-expanding thought is that this road Im on will eventually take me to Cape Town the same road these people around me are taking to get to their offices and factories and call centres on this wet October morning.

The adrenalin pumps through my veins, transmits itself through the bars to the forks and the tyres to the tarmac. I may be swaying all over the road like a drunk coming home from a Christmas party, but the road is mine, all mine.

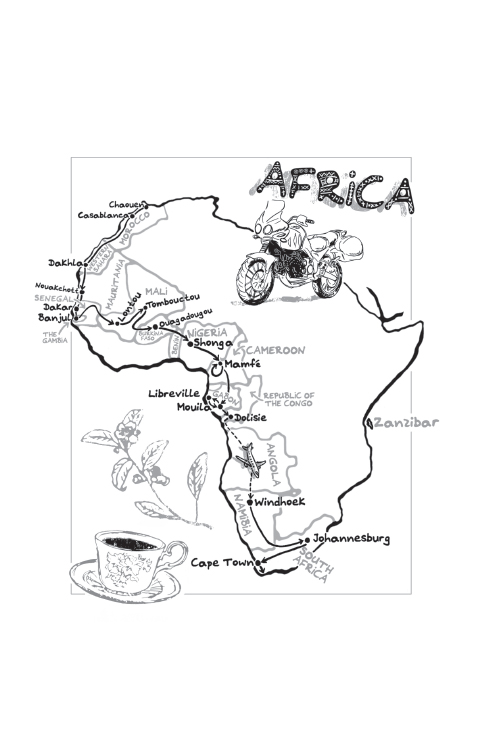

It takes a week to reach the southern Spanish port of Algeciras, skimming along the surface of the washed-out autoroutes. The town has the feel of North Africa about it: the dark-skinned men walking about the city in slippers and djellabas, the unruly moustaches, the tea served in miniature glasses, the hostel that doubles as a brothel. The view from a hill overlooking the port serves to heighten the excitement of tomorrows ferry to Morocco. Im here for one of the reasons this city exists to disgorge the helpless, curious European, in above his head, to AFRICA.

Im going not because I think I belong but rather because I want to belong. Since I got married to Olive, a South African, in Johannesburg in 1984, I have felt something dragging me back to the continent. The pull has been strong enough for me to want to get close up, to experience Africa outside of my usual frustratingly clinical arrivals at Joburg or Cape Town airports. I feel as though Im on a ten-metre diving board about to take the plunge for the first time. I want to immerse myself in Africa on my quest for the ultimate cuppa, but more of that later. I know the continent is out there waiting for me and I can barely contain myself. As a family catchphrase goes, Im so happy, I envy myself.

Less than a hundred kilometres from the ferry, I decide to have an easy first day in Africa and ride up to Chaouen in the Rif Mountains. The whitewashed village, aglow in brilliant sunshine, welcomes me to the continent with a warm breeze as I turn away from Europe and face south towards the rest of Africa.

Later, at five oclock, the hungry villagers will soon be going home to the family evening meal theyve been looking forward to since sun-up. The market in the Moroccan village is heaving, and the sale from the stalls of live and recently deceased chickens, dates and festival cakes is peaking. A bird is chosen from the holding pen behind the head of an unshaven man in a once-white coat; then another man wrings its neck and feeds it whole into the de-feathering machine, covering himself with soft down and warm blood. Chicken tajine for supper tonight, I think.

Mohammed and I take an aimless walk through the streets. One building with a huge pile of roughly cut logs leaning against it catches my eye. We approach and I see that the wood is used to fuel the furnace for a hammam. We descend into the furnace room, a small dark space with a man dozing in his cot, a pot of tea beside him.

He is furnace man, Mohammed tells me, redundantly. Twenty-four hours in a day.

The furnace stoker must get through gallons of rehydrating tea each day to combat the debilitating effects of the unbearable heat, which I cannot tolerate for more than a few seconds. We emerge, gratefully, back up into the light.

The sight of the tea brings on a thirst and I suggest to Mohammed that we find a caf for some mint tea of our own. He gives me a quizzical look. Nonchalantly, he clears his throat and coughs up a large spit ball which lands at his feet.

Guide would be too grand a description of Mohammeds services, but he is available to aid the stranger in town, interpret and answer questions. He has an impressive habit of hacking up great gobs of phlegm to punctuate his conversation. Much as I might erm and umm my way through a dialogue, he uses throat clearing to emphasise the importance of a particular point, to critique the ways of the world, to clear his airways and just to amuse himself.

We skip up a narrow staircase to an empty rooftop tea room.

There are forty thousand peoples in this village; it is very old but lots of poor here and around, hack , but we live in beautiful place. Look around. Spit . Many Berber people come and sell food in the medina but I , says Mohammed, stressing the distinction, I am Arab . Big garggly hack.

Mohammed leans back on the low wall tracing the perimeter of the roof and shows off his Nike T-shirt with its slogan Hello There. We look out over the town clinging to the hillside. Chaouen is a beguiling place full of gracious, slippered people scuffing along the dusty streets and immaculately dressed children skipping home from school, their angelic faces rimmed by coloured head scarves. Occasionally, old women walk by dressed in four-cornered straw hats with blue pompoms attached. They all squint into the late afternoon sun, some stopping to look up and observe the stranger.

Mohammed tells me he is penniless he pulls out his trouser pocket linings as some sort of proof, then dredges up a document from his back pocket from the Court of Justice administering a fine of 1,000 dirhams which must be paid by a date, conveniently, a few days hence.