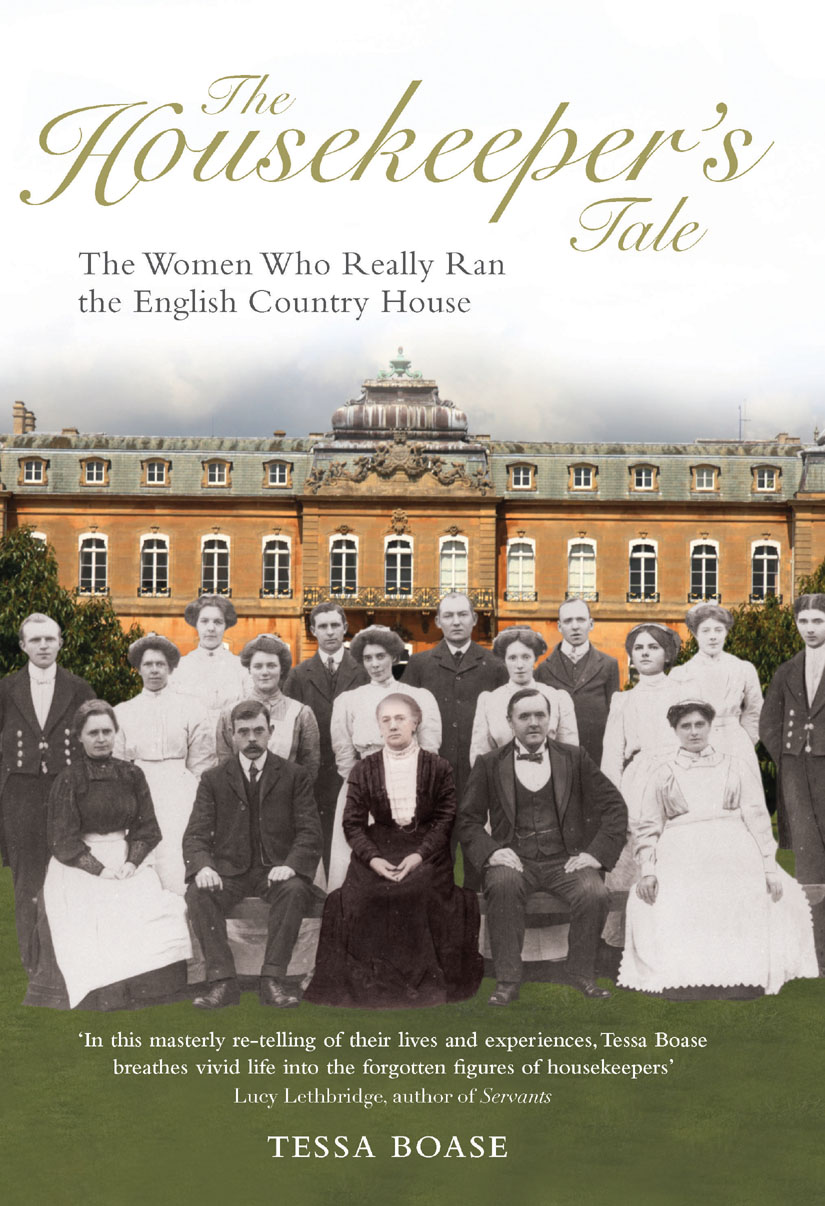

The Housekeepers Tale

The Women Who Really Ran the English Country House

Grace Higgens Story

By TESSA BOASE

First published in 2014

by Aurum Press Ltd, 7477 White Lion Street, London N1 9PF

www.aurumpress.co.uk

This eBook edition first published in 2014

All rights reserved

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly

eBook conversion by Quarto Publishing Group USA

Digital edition: 978-1-78131-417-3

Hardcover edition: 978-1-78131-043-4

What follows is extracted from The Housekeepers Tale by Tessa Boase.

It tells the story of how these women, who were part of a wider narrative, were so central to the social tapestry of Britain yet for so long their voices lost to history. Exploring the lives of these housekeepers and the conditions of their tenureand ultimately, departurewe gain a better understanding of each of the time periods they worked in. Starting in the early Victorian period through the Georgian period and two World Wars right up to post-war Britain.

If you would like to read about the lives of the other four women, you can find them all together in The Housekeepers Tale.

Part 1

Grace Higgens

Charleston, East Sussex 19201971

I cannot regard Grace as anything but a family appendage.

DUNCAN GRANT

Timeline

1931 | Five per cent of England and Wales employs a resident domestic. |

1933 | Dettol, antiseptic liquid, goes on sale. |

1935 | Penguin brings out paperback books at 6 pence each. |

1936 | George V dies. Edward VIII succeeds and abdicates. George VI becomes King. |

1938 | First electric steam iron. |

1939-1945 | The Second World War. Half a million women employed by the armed forces. |

1939 | Instant coffee first available. |

1940 | Ration books introduced. |

1943 | Conscription of all single women aged 19 to 24. |

1946 | The biro invented. Family Allowances introduced for the second child onwards. |

1947 | Education Act: school leaving age rises to 15. |

1948 | National Health Service founded. |

1949 | Family Planning Association clinics open at the rate of five weekly. |

1951 | 0.72 million servants in England and Wales, a fall of 46 per cent. Britains first automatic washing machines. |

1953 | Over 20 million people watch Elizabeth IIs Coronation on television. |

1959 | The Morris Mini-Minor goes on sale for 500. First Spanish package holiday: 15 days in Majorca for 55 guineas. |

1960 | Contraceptive pill available to women. |

1963 | She Loves You by the Beatles. Assassination of President John F. Kennedy. |

1966 | England wins the football World Cup. |

1971 | Upstairs, Downstairs airs on ITV. |

I

Forty-Four Little Books

H ere is a different story. Our housekeeper occupies not a grand country house but a ten-bedroomed, isolated farmhouse at the foot of the South Downs. She has none of the obvious trappings of power: no black dress, no keys around her waist, no wood-panelled sitting room with fireplace stoked by a cowed young maid. There is, in fact, no retinue of underlings to keep in line: she has just the house (damp, decaying) as her gruelling charge. She lives in close proximity to her mistress, eventually to share a familiarity unimaginable to previous generations on both sides of the class divide.

The tale of Grace Higgens is a story of loyaltyexcessive loyalty, perhapsand it unfolds over fifty years of the greatest period of social change Britain has yet seen, defined by the central event of the Second World War. Grace entered service as a housemaid for the Bell family in 1920, when deferential teenage maids still curtsied and averted their eyes and cooks were hidden away in dark basement kitchens. By the time of her retirement in 1971 she was the last of her line: an anachronism serving a household of one in the same year that a drama called Upstairs, Downstairs made its debut on ITV. No one in 1971 had live-in servants. No one could find live-in servants. Or if you could, you kept quiet about it.

Even though Grace married and became a mother, she chose to remain living in the freezing attic at Charleston working for Vanessa Bell (on 5 a week, bath night Fridays) right up until her sixty-seventh year, though her husband Walter clearly wished it otherwise. Having finally made the break, she was found a decade later by a Sunday Times reporter sitting in her Ringmer chalet, fulminating about a disrespectful TV documentary on the Bloomsbury Group (What rubbish!). Through retirement and right up to her death, Grace kept scrapbooks of every press cutting she could find on the circleher circle.

The individuals she worked for hadand still havea reputation for being wildly unconventional, so much so that it is odd to think of servants being a part of their mnage at all. The household of artist Vanessa Bell waxed and waned over Graces half-century to include her separated husband Clive Bell, their children Julian and Quentin and her one-time lover and lifelong companion, the homosexual artist Duncan Grant. There was also her younger daughter Angelica, secretly fathered by Duncan, whom Clive Bell had agreed to pass off as his own. Vanessas sister, the author Virginia Woolf, was central to this family, as was her husband Leonard Woolf. So intriguing and well documented is the group that its clamorous voice threatens to overwhelm this housekeepers tale. My aim is to turn down the volume on the Bloomsbury Set, on its clever irony and self-conscious wit, and to coax into life the unheard voice of domestic servant Grace Higgens.

After her death in 1983, a hoard of forty-four little books was discovered among Graces possessions. She had been an inveterate diarist. From the first ruled exercise book kept beneath her mattress, aged 16, to the hardbacked, illustrated recipe diary written in her seventy-ninth year, Grace recorded her day-to-day life with an eye for pithy detail. There are the Provenal peasants on her first trip abroad with the Bell family in 1921, who came & stared & jabbered in French; the dinner guest resembling film star Fatty Arbuckle; the Woolfs on their bicycles in Sussex looking absolute freaks, Mr Woolf with a corduroy coat which had split up the back like a swallow tail, & Mrs Woolf in a costume she had had for years. Laterthirty or forty years laterGrace was still trenchant. Sat for my portrait after lunchI had a peep & think I look a peevish woman; The house looks as if a tornado had hit it; Heard our voices on Tape machine. Sounded ghastly; and, returning to France for the last time in 1960, I spilt so much Chanel 5 on myself I smelt like a whore, but better I hope.