This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly

What follows is extracted from The Housekeepers Tale by Tessa Boase.

It tells the story of how these women, who were part of a wider narrative, were so central to the social tapestry of Britain yet for so long their voices lost to history. Exploring the lives of these housekeepers and the conditions of their tenureand ultimately, departurewe gain a better understanding of each of the time periods they worked in. Starting in the early Victorian period through the Georgian period and two World Wars right up to post-war Britain.

If you would like to read about the lives of the other four women, you can find them all together in The Housekeepers Tale.

Part 1

Ellen Penketh

Erddig, North Wales 19021907

The princely salary of 45 a year.

MR ARTEMUS JONES, BARRISTER FOR DEFENDANT ELLEN PENKETH

Timeline

1901 | Life expectancy for men is 45; for women, 49. First vacuum cleaner patented. Heinz Baked Beans first sold by Fortnum & Mason for 9 pence a can. |

1902 | Pharmacy Act: dangerous chemicals no longer sold in domestic-shaped bottles. |

1903 | Mrs Emmeline Pankhurst and daughters start the Womens Social and Political Union to campaign for womens suffrage. The Daily Mirror launched, initially as a womans paper. |

1909 | Lloyd Georges Peoples Budget speech, promising wealth redistribution. Persil washing powder arrives in British shops. |

1910 | Londons Selfridges introduces a cosmetics counter, a year after the store opens. Ponds Vanishing Cream and Cold Cream first marketed. |

1911 | National Insurance Act: insures employees against ill health and provides some unemployment benefit. 1.4 million indoor servants working in Britain. |

1912 | RMS Titanic sinks after striking an iceberg. Hullo Rag-time! opens at London Hippodrome and runs for 451 performances. Suffragettes resort to violencedeeds not words. |

1913 | Suffragette Emily Wilding Davison throws herself under the Kings horse on Derby day. |

I

The Corridor

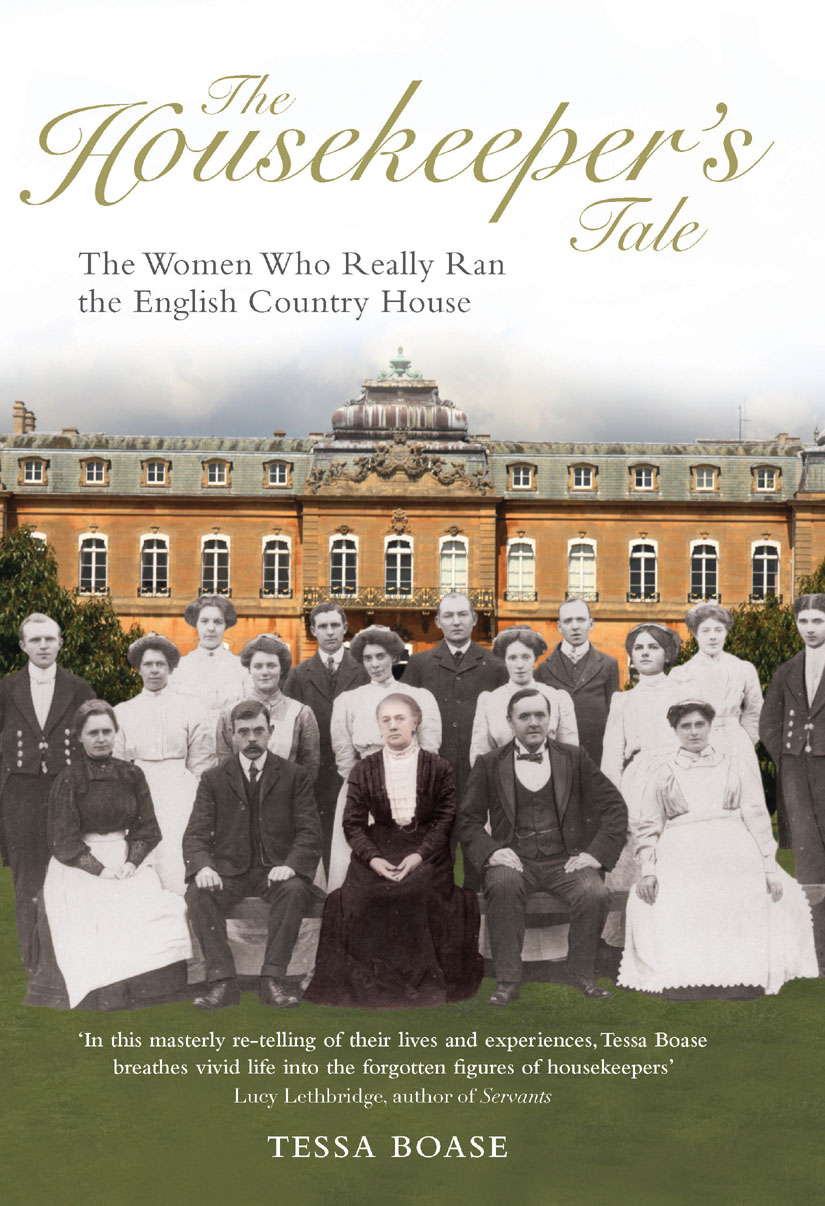

T his story starts, and ends, with a photograph.

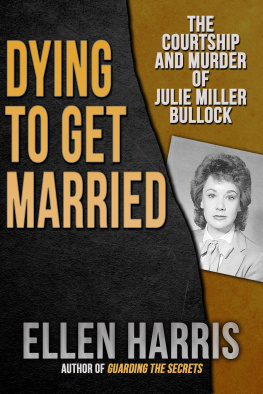

It is the one truestraightforward, unbiasedrecord to survive. And it is such a handsome photograph: the oval, clear face; the slightly amused eyes. By Edwardian standards of beauty, Ellen Penketh has a certain allure. There is something of the Gibson girl in that longish face and sporty jaw, the hair piled up on her head in the contemporary pompadour style (but not too high: she was a servant, after all). Yet she lacks the haughty, slightly pitying look of those Belle poque women drawn by Charles Dana Gibson. Ellen Penkeths expression is hopeful, like the posy of fake flowers she is holding. It is the sort of studio portrait a working-class girl might send to a fiancand it is in stark contrast to the photo gallery of stern-faced spinsters who line the basement corridor at Erddig Hall.

Servants who worked for the Yorke family in the early twentieth century tramped past these two dozen portraits daily on their way from laundry to scullery, butlers pantry to servants hall. The passage is dark, as Erddig refused to succumb to the modern rage for electricity. It is also terribly cold, as the wind from the far Welsh hills lashes the west front with great determination, forcing leaves under ill-fitting doors and draughts through old sash windows.

The photographs are enlarged, retouched and boxed in by screeds of verse celebrating each individuals years of service, their dedication, their preference for life at the big house to any other sort of life at all. And for some thirty years and more/The cares of Office here she bore is typical. How did the Yorke servants feel, hemmed in by all these loyalty portraits? There is Harriet Rogers (heavy-lidded stare, thickly veined hands), forty-four years in service first as nurse, then ladys maid, then cook-housekeeper. There is gardener George Roberts posing with his wife, who holds in her lap a portrait of her mother, also in service at Erddig. John Jones (slightly boss-eyed, saw in hand) was photographed in 1911, thirty-three years after he entered service as a carpenter. The message is clear: stick with us and well look after you. Erddigor Erthig, to the Welshwas an anchor in a fast-changing world.

Each poem, bashed out on a typewriter, is signed P.Y.Philip Yorkeand dated 1911 or 1912. What happened to make Squire Yorke abruptly start this celebratory exercise in verse? Many of these servants were long dead or departed when he began his taskwhy the need to backdate so assiduously? And why were so many new portraits of old servants taken at this time? They were done, ostensibly, for continuitys sake: the servants hall at Erddig is famous for ten oil portraits of servants, complete with rhyming couplets, commissioned by his grandfather and great-grandfather. But in truth, it was more complex than this. The answer is hinted at in the verse Philip Yorke II wrote for Miss Brown, housekeeper at Erddig from 1907 to 1914.

Twelve years or more did intervene

Before Miss Brown came on the scene

Of Housekeepers we estimate

We had in turn no less than eight

But since Miss Brown her rule begun

Our lot has well and smoothly run,

And the result may now be classd

As worth the fire thro which we passed.

P.Y. 1912

Five years previously the Yorkes had been caught up in a very public scandala scandal that did deep and profound damage to their patriarchal belief in staff loyalty. The woman at its centre worked at Erddig as cook-housekeeper for five years, then was purged from the family narrative. The portrait of Ellen Penketh did