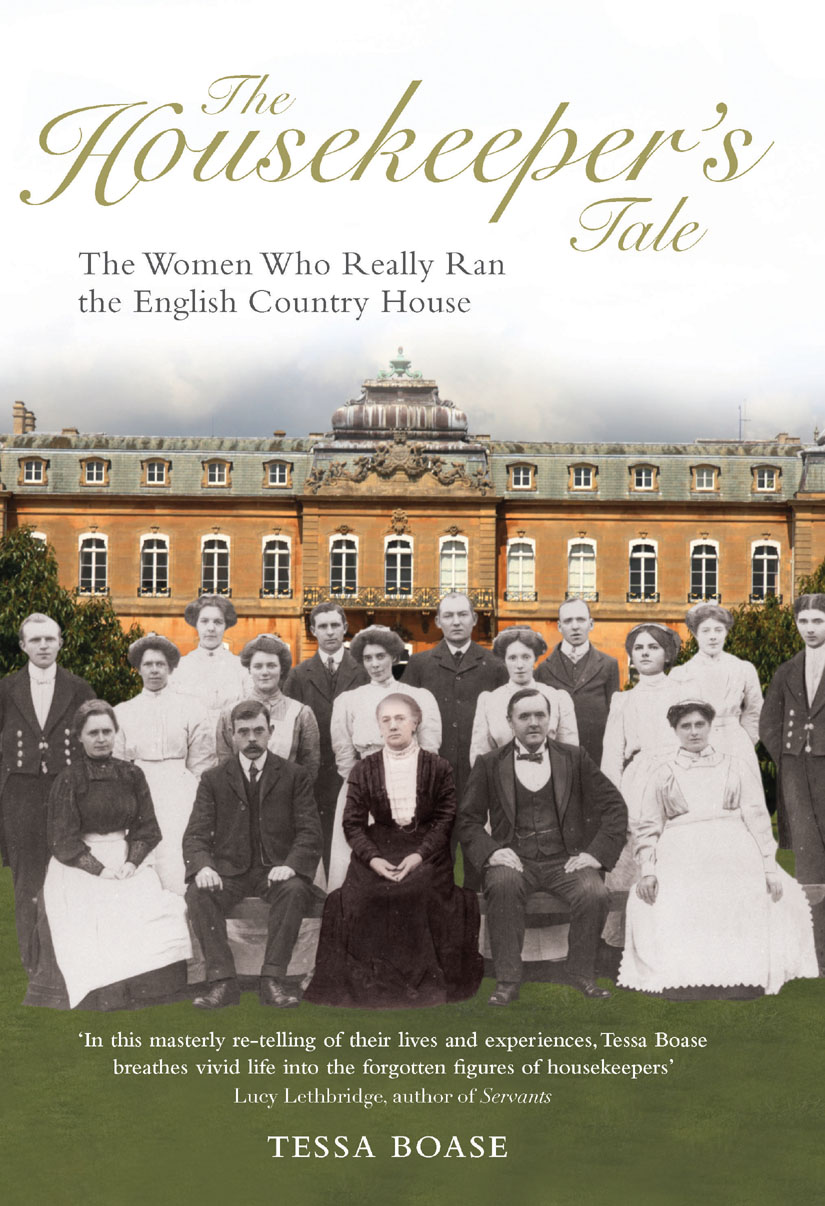

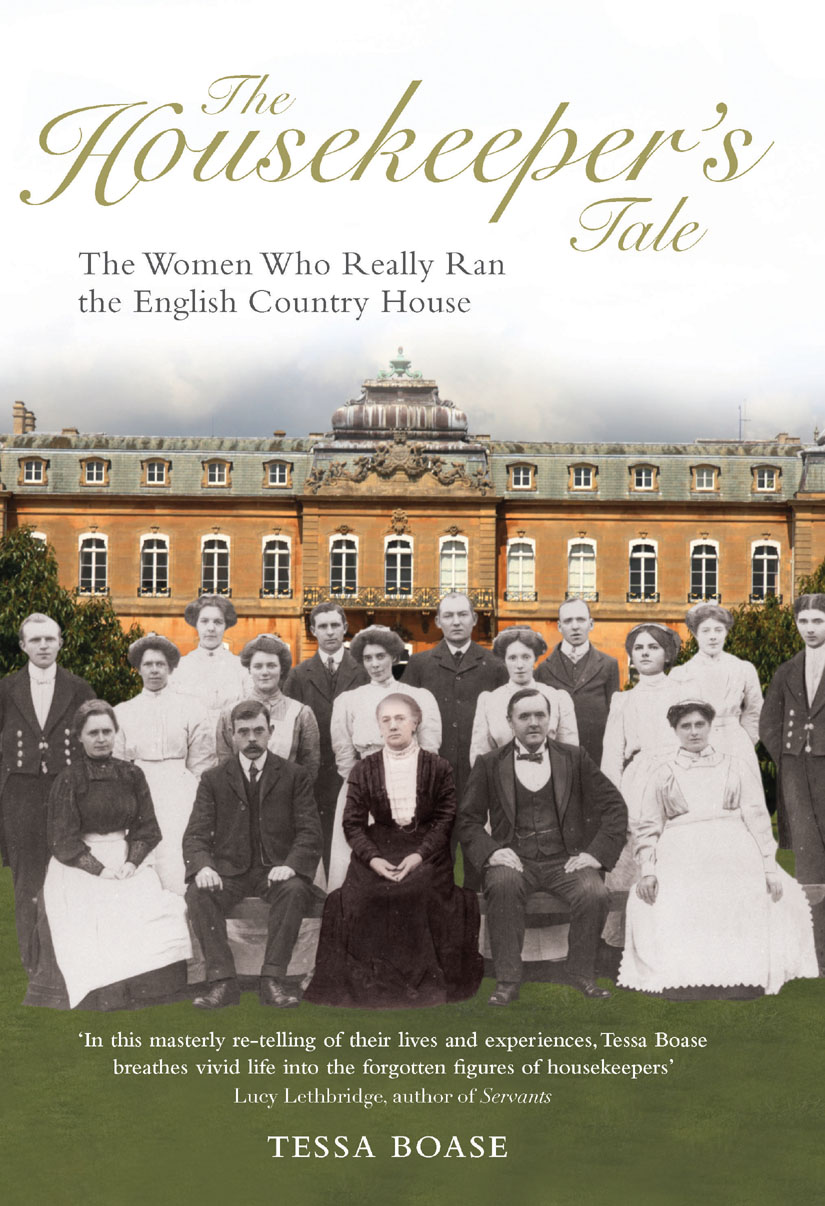

The Housekeepers Tale

The Women Who Really Ran the English Country House

Dorothy Doars Story

By TESSA BOASE

First published in 2014

by Aurum Press Ltd, 7477 White Lion Street, London N1 9PF

www.aurumpress.co.uk

This eBook edition first published in 2014

All rights reserved

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly

eBook conversion by Quarto Publishing Group USA

Digital edition: 978-1-78131-413-5

Hardcover edition: 978-1-78131-043-4

What follows is extracted from The Housekeepers Tale by Tessa Boase.

It tells the story of how these women, who were part of a wider narrative, were so central to the social tapestry of Britain yet for so long their voices lost to history. Exploring the lives of these housekeepers and the conditions of their tenureand ultimately, departurewe gain a better understanding of each of the time periods they worked in. Starting in the early Victorian period through the Georgian period and two World Wars right up to post-war Britain.

If you would like to read about the lives of the other four women, you can find them all together in The Housekeepers Tale.

Part 1

Dorothy Doar

Trentham Hall, Staffordshire 1832

It is quite impossible in such an establishment to permit of her breeding.

JAMES LOCH, CHIEF AGENT TO THE SUTHERLANDS

Timeline

1830s | Stagecoach from London to Edinburgh takes two days as turnpike roads improve. Railway Mania begins. |

1830 | William IV ascends throne, aged 64. First D.I.Y. knitting book, Ladies Work for Sailors. |

1832 | Great Reform Act: men with homes with an annual value of 10 get the vote. |

1835 | First pre-packaged baking powder on sale. |

1836 | Dickenss first novel The Pickwick Papers serialised. |

1834 | Poor Law Amendment Act: the destitute refused parish relief and forced into the workhouse. |

1837 | Victoria becomes Queen, aged 18. |

1839 | First Indian tea for sale in London. |

1840s | Railways expand to most towns and villages. Food in tin cans becomes more widely used. |

1840 | First postage stamps: Penny Black and Twopence Blue. |

1841 | Londons Reform Club installs gas cookers, among first in the country. |

1842 | Beechams Pills first marketed. Coal Mines Act: Women and children under ten prohibited from working underground. |

1849 | Safety pin invented. |

I

Abominably Rich

T hey made a formidable cabal, the five housekeepers of the Duke of Sutherland. Like pawns on a chessboard they were ranged across the country: Mrs Spillman sat at Dunrobin Castle in the far north-east of Scotland; Mrs Cleaver at the southernmost extreme, West Hill in Wandsworth, Surrey. In the capital, the tireless Mrs Galleazie reigned over Stafford House, scene of much entertaining. Mrs Kirke presided over the new hunting lodge, Lilleshall Hall up in Shropshire; and Mrs Doar sat plumb in the middle: keeper of Trentham Hall, Staffordshire.

Letters flew between these five women daily: hastily scrawled notes with advance warning of the familys imminent arrival or departure; requests to send Staffordshire partridge, kid boots from London, whisky barrels from Scotland, more ripe pineapples for this weeks reception at Stafford House. Sicknesses were communicated, staff vacancies filled and in-house gossip quenched. A nobleman could not hope to employ five more discreet or implacable custodians.

This is the story of one of these women: a housekeeper who, after fourteen years loyal service, fell spectacularly foul of her employers. The year was 1832, a time of great political upheaval in Britain. Dorothy Doar was a small but vital cog in the enormous machine servicing the richest, most powerful and probably most disliked family of her day. Given the size of this machinethe Duke and Duchess of Sutherland moved between not two, but five housesit is by sheer chance that the sorry tale of Mrs Doar has survived at all. But, like a gnat squashed between the pages of a book, I came across her in a random bundle of otherwise dry correspondence between two land agents; a bundle tied with white ribbon and filed away in the vast Sutherland Collection at the Staffordshire Record Office.

Written over the course of two months in 1832, this series of letters is highly unusualunusual because the housekeeper leaps brightly off the page. Dorothy Doar lives; her character and foibles are laid bare. Her tale unfolds in a drama that no wage book, store-cupboard inventory or housekeeping accounts book can hope to compete with. The letters throw light on basement politics between upper servants in the Regency era: back-stabbing, rumour spreading, leapfrogging for advancement. There are hints of sexual liberties; of houses so rarely visited by their owners that they develop their own unconventional codes of conduct. The letters show us, too, how the uber-aristocracy of the day treated their upper servants.

For such an important family, a surprising amount of time and energy was put into the relationship between mistress and housekeeper. You could not run five houses without the likes of Mrs Doar. She was somebody to be kept sweet: to be soothed, praised and assisted. The relationship was based on loyalty, honesty and trustwith the servant always aware of the immense gap between the haves and have-nots. No servant, no matter how senior, could take anything for grantedas Dorothy Doar was to learn to her cost.

Mrs Doars job was to facilitate the most luxurious lifestyle pursued in Britain at that time. Her employer was George Granville Leveson-Gower (pronounced Looshun Gore), known to his housekeeper in 1832 as the Marquis of Stafford, just one year off being made the Duke of Sutherland, the title by which this lineage is remembered. He had, by virtue of an astute marriage, created a dynasty second only in wealth to the royal family. Quite simply, the Staffords owned much of Britain, and as a consequence were hated and revered in equal measure.