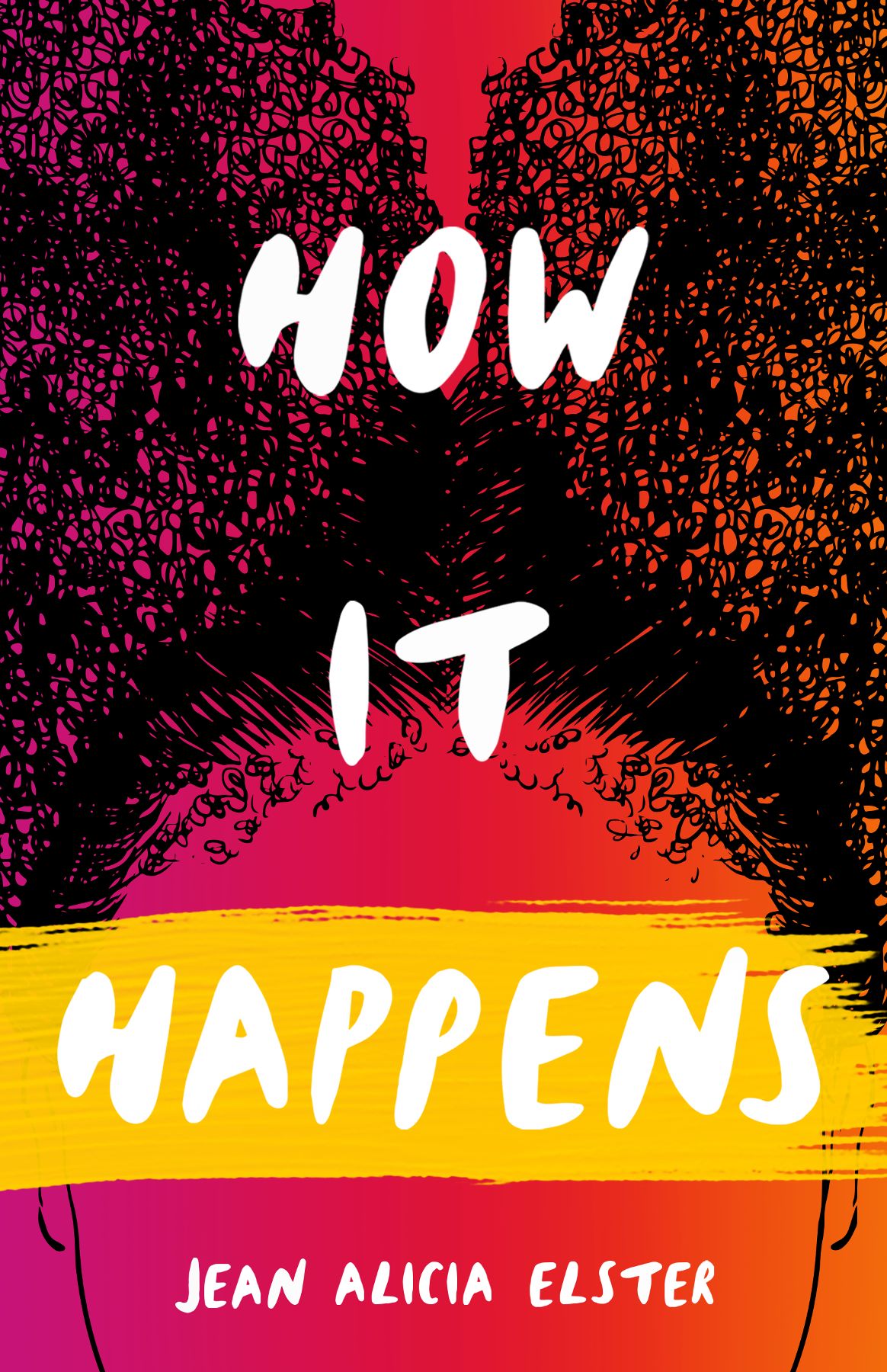

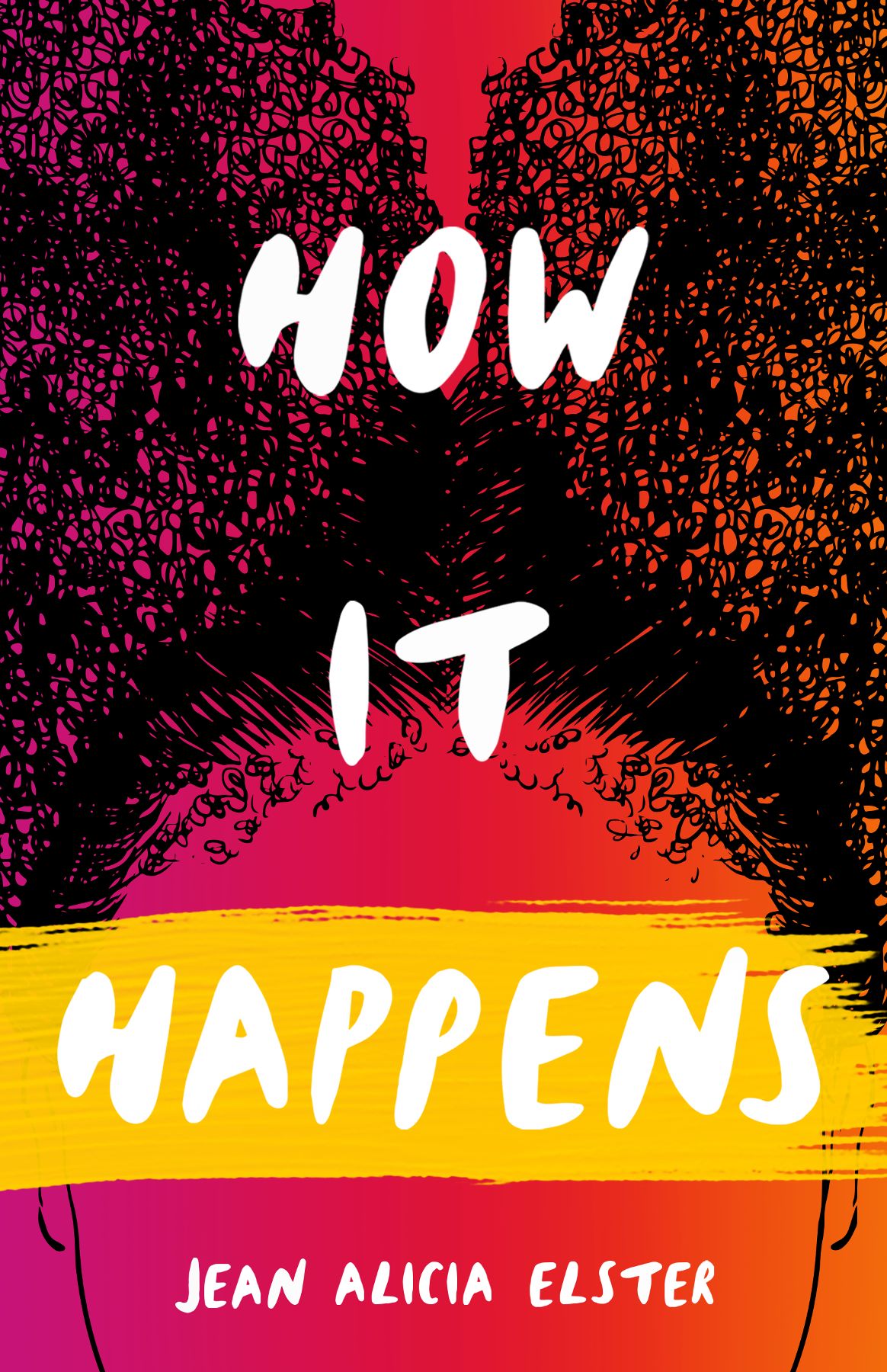

How It Happens

Great Lakes Books

A complete listing of the books in this series can be found online at wsupress.wayne.edu.

Editor

Thomas Klug

Sterling Heights, Michigan

How It Happens

Jean Alicia Elster

Wayne State University Press

Detroit

2021 by Jean Alicia Elster. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without formal permission. Manufactured in the United States of America.

ISBN: 978-0-8143-4869-7 (paperback); ISBN: 978-0-8143-4870-3 (e-book)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021934632

Cover vector art Shutterstock.

Cover design by Chelsea Hunter.

Wayne State University Press rests on Waawiyaataanong, also referred to as Detroit, the ancestral and contemporary homeland of the Three Fires Confederacy. These sovereign lands were granted by the Ojibwe, Odawa, Potawatomi, and Wyandot Nations, in 1807, through the Treaty of Detroit. Wayne State University Press affirms Indigenous sovereignty and honors all tribes with a connection to Detroit. With our Native neighbors, the press works to advance educational equity and promote a better future for the earth and all people.

Wayne State University Press

Leonard N. Simons Building

4809 Woodward Avenue

Detroit, Michigan 48201-1309

Visit us online at wsupress.wayne.edu

To my ancestors, Addie Jackson and Tom Martin

Because of you, I am

Contents

Many people have contributed to my ability to write this book: the writers craft, though it is a solitary endeavor, is not pursued alone. While I will not try to list them all, I, in particular, offer my utmost gratitude to the following people

To Tim Pulley, the genealogy department supervisor at Clarksville/Montgomery County Public Library in Tennessee, who unearthed and shared a treasure trove of documents and information on the Jackson and Henry/Martin family histories during my visit in the year 2000;

To the Ragdale Foundation, Lake Forest, Illinois, for that first writers residency, where I wrote the initial draft of the opening chapters of this book;

To my Wayne State University Press editors, Kathy Wildfong and Annie Martin, for warmly welcoming book 3 of the Ford family trilogy and for pushing me out of my comfort zone to complete the book they both knew I could write;

To my dear son, Isaac Elster, editor extraordinaire, whose deep read of chapter 1 of this book helped to set the remaining chapters on the right course;

To my cousin, Darryl Ford Williams (daughter of Douglas Ford Jr.), for unwittingly prodding me along as I worked to complete this book;

To my deceased grandmother, Maber Jackson Ford, for sharing her story with me, over and over, until it became a part of my story;

To my deceased mother, Jean Ford Fuqua, and my aunt, Maber Ford Hill, for wanting me to know what they remember;

To my sister, Gwynn Fuqua, for helping me fit the pieces together;

But, most of all, to my husband Bill, for being the light in this writers life and living proof that the greatest of these is love.

Grandma, are you white?

Its one of my earliest memories as a toddler: standing in my grandparents kitchen, looking up at my grandmothers face as she sat at the kitchen table and asking her if shes white. I had no idea what I was asking or what that term white meant when it was applied to another person. Obviously, I knew that her skin was very much lighterbrighter, my grandmother would saythan my brown skin. And I had also obviously heard that word bandied about as adults talked around me. But at that age I had no concept of race or ethnic heritage. I just knew she looked different from the other family members that I interacted with.

I also did not know this: her color represented a vivid reminder of the history of racial relationships in the American South as it relates to the sexual interactions between blacks and whites and the resulting offspring that did often come from those unions. That history is fraught with complexities.

A response to those relationships was the term miscegenation, which was created in the South in 1863 within the context of American racism and slavery. The Merriam WebsterDictionary defines miscegenation as a mixture of races especially: marriage, cohabitation, or sexual intercourse between a white person and a member of another race. It was a dominant term in many of the race laws that proliferated throughout much of the country. Those laws forbade black people from partaking in many aspects of American life but, in particular, banned intimate relationships between whites and people of color. The focus, if not in explicit words then at least in intent, was especially upon those relationships between black men and white women.

When those banned intimate relationships in the race laws occurred between white men and black women, the dynamic was altered considerably. Because beginning with the time of black enslavement in America when blacks were considered the owners chattel, or human property, white meneven those who did not own enslaved womencould force a black woman to submit to an intimate relationship without fear of ever facing the consequences of having broken one of those race laws.

Now, any sexual encounter that occurs without the consent of one of the parties or that occurs after a party says, No, is rape. Period. And even more compelling are those instances where a party is afraid to say, No, or when they know that saying no is not an option. It is still rape, and the situation and its consequences become all the more chilling.

This book begins in the postReconstruction era of American history, in the year my grandmother was born in 1890 in Clarksville, Tennessee. It incorporates many of the snippets of family and social history that my grandmother shared with me while I was a young child and, later, while growing up. As a child, I did not know the meaning of or the social and familial impact of many of the seemingly innocuous tales she shared with me. But what became clear to me as I reached adulthood and began to truly absorb much of what she had told me, was that even though those postReconstruction race laws have, since the 1960s, been repealed or struck down by judicial venues all the way up to the United States Supreme Court, the effects of the race-based societal and sexual double standards and injustices that emanated from those laws are still an ingrained part of our American culture. The results will continue to be felt in this country for generations to come.

1890

Boardinghouse

Addie Jackson felt the spasm coming beneath her belly as she made her way out of Tom Mitchells room with his grandmothers quilt wrapped loosely around her. It was obvious to anyone who looked at the way she carried herself that the baby was due any day now. She leaned toward the railing along the second-floor hallway, then let the quilt fall as she turned, fell forward, and grabbed the rail with both hands, grabbed it with all of her might. She crouched down in a squat as the spasm took hold of her. She tried to hold in the howl as the pain welled up inside, but it was no use. She could not keep silent.

She closed her eyes and screamed, Aaarrgh! She held the railing so tightly she felt it move, as if it might give way.

Addie? Addie, hold on now, girl! Addie looked down through the railing posts. It was Tom, standing in the foyer just beneath the railing. Good Lord, she heard him whisper, dont let that child be born here at Mrs. Beattys place. She could see how he strained to see her up beyond the foot of the railing. Addie, he said in full voice, listen to me now. Ill be right there. Im still looking for Mrs. Beatty...

Next page