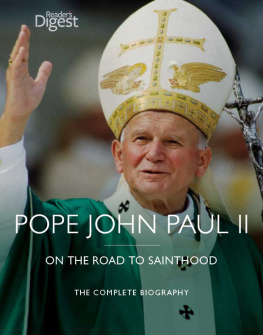

JOHN PAUL II: THE PATH TO SAINTHOOD

Dedicated to the Staff at the Apostolic Palace, who shared twenty six years of their lives with Blessed John Paul II. With affection and respect.

MICHAEL COLLINS

John Paul II

The Path to Sainthood

First published in 2009 by

The Columba Press

55A Spruce Avenue

Stillorgan Industrial Park

Blackrock, Co Dublin.

Designed by Bill Bolger

Printed by

Athenaeum Press, Gateshead

ISBN 978-1-85607-656-2

Preface

I first met Pope John Paul II in late June 1979. A friend and I had hitch-hiked from Dublin to Rome. We had both commenced studies for the priesthood the previous year. One morning, we received an invitation from the Popes private secretary, Father John Magee, to meet the Pope. The pontiff was staying for a brief period in the Tower of St John in the Vatican gardens while his apartments were being renovated.

I recall how he walked into the room, exuding energy and cheerfulness. We were introduced to him along with other guests. After a short greeting, we had a photograph taken and then the pope went out through the door, where a car was waiting to take him back to the Apostolic Palace for the days meetings. I remember been startled as he slapped me on the shoulder as he left.

Fr Magee also sat into the car, and I looked out the door to signal my appreciation for his kindness in arranging the meeting. He discreetly nodded to me. The Pope, however, leaned forward and, with a broad smile on his face, gave me the thumbs up sign.

Over the next twenty five years, I met Pope John Paul on some thirty occasions. Several times in the early years I met him in the gardens of Castelgandolfo, when I spent my summers working as a guide in St Peters Basilica. After ordination, I often concelebrated Mass either in his country residence or in the Vatican. He was always ready to chat. As a linguist, he enjoyed bantering in various languages.

Monsignor Thu, his Vietnamese secretary, told me that the Pope was deaf in one ear, which explained why he always turned to one side when talking with individuals.

I met Sr Tobiana on several occasions and was always deeply struck by her sincere love for the Pope and the care she showed him in his old age and illness. It was to her that he whispered his last words on earth and it was she who held his hand as he slipped away to the House of the Lord.

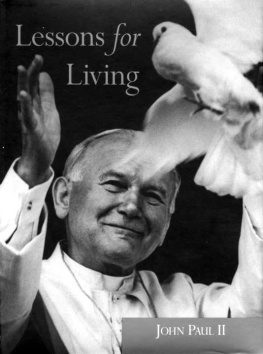

As the years went by, the strong athletic man shrank in size, but he grew in my appreciation. His acceptance of physical illness and pain was extraordinary but his sheer determination was impressive. The last time I saw him was in the Papal Apartments one Sunday evening six months before he died. His face was now a mask, his body a like a crumpled blanket. Yet behind the pain-filled eyes was the soul of a man who burned with a deep love of Jesus Christ. He remains my inspiration and I realise that I am blessed to have met him.

Michael Collins

A S HE LAID HIS HEAD on the pillow in the early hours of 17 October 1978, Karol Wojtyla knew he would find little rest. Some nine hours earlier he had been elected 264th pope, successor to the Apostle Peter, taking the name John Paul II.

The tumultuous hours which followed were but the presage of the changes which were about to engulf him. Emerging onto the balcony of St Peters Basilica to give his blessing to the city and the world, Karol Wojtyla stepped into the blinding light of history.

The conclave which had elected him, with some 100 of the possible 111 votes, had ended shortly before 6.00 pm. Less than two months earlier, the same cardinals had elected Albino Luciani, the Patriarch of Venice, as Pope John Paul I. The smiling Venetian had quickly won the hearts of many, but his sudden death after thirty- three days in office had caused confusion and dismay.

The new pope from Poland had asked the cardinals to remain with him until the next morning, when they would celebrate the first Mass of the new pontificate in the Sistine Chapel. After a genial meal, during which the cardinals sang him the traditional greeting Polish greeting Sto lat (May you live a hundred years) he had retired to his cell to outline a homily for the Mass.

The largest voting bloc had been the 55 Europeans, of which 25 were Italians. The sudden death of Pope John Paul I on 29 September had thrown many of the cardinals into panic. A new criteria was needed. The next pope ought not to be too elderly, and certainly should be in good health. Nor indeed should he be too young. The old Italian saying applied we want a Holy Father, not an Eternal Father

The front-runners were Cardinal Giovanni Benelli, Archbishop of Florence, and Cardinal Giuseppe Siri of Genoa. Benelli, a long time Vatican diplomat, represented the moderately liberal cardinals. Siri had already given an interview to a newspaper, published on the eve of the conclave announcing the conservative changes he would introduce if elected.

Each morning and afternoon, the cardinals cast their votes in two ballots. Dressed in scarlet robes, each stepped up one by one to the altar beneath Michaelangelos towering fresco of the Last Judgement, calling on God to witness his vote. The folded ballot paper was placed on a silver paten dish, and then tipped into a chalice. After each vote, the ballots were tallied, and the names of the leading candidates called out.

After each ballot, the papers were burned in a stove. A chimney, leading from the chapel to the roof, was visible to the crowds gathered in St Peters Square. Each unsuccessful ballot curled up in black smoke. The people drifted off into the surrounding bars to have a coffee and speculate on the proceedings inside the chapel. The papacy is the longest surviving non-hereditary monarchy in the world. Media networks mulled over the possible election of a new pope and what it would mean to one billion Catholics and the world at large.

Many were critical of the medieval practice of electing the pope, introduced almost a thousand years earlier. The exclusion of lay voices, of women, of a broad spectrum of experience, struck many as outmoded and unlikely to produce the best leader of the Catholic Church. For now, the conclave was the only way to elect a pope, and the cardinals were intent on their work.

The cardinals themselves were also uncomfortable, with one hundred and eleven largely elderly men forced to live together for an indeterminate period. While many had complained in August of the sweltering temperatures, now they grumbled as the autumn drafts chilled their temporary accomodation. Fortunately modern conclaves were relatively short lived affairs. The last lengthy conclave had lasted from 30 November 1799 to 14 March 1800, when Cardinal Giorgio Chiarmonti was elected Pius VII on the Island of San Giorgio in Venice. The longest conclave had been held in the town of Viterbo. Lasting 33 months between 1268-71, the cardinals finally settled on a candidate, Gregory X, when the mayor of the city had stripped the roof from the room in which they met and had reduced their food rations.

Only when white smoke unfurled into the dark Roman night sky would everyone know the conclave was over and a new pope had been elected. The piazza would fill rapidly as news spread throughout the surrounding streets and people raced to hear the historic announcement.

Next page