The rich are different, novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald is supposed to have said. To which his friend Ernest Hemingway was said to have replied: Yes, they have more money.

This never happened, apparently. Those who know about these things say the exchange was entirely apocryphal. It was made up from two real quotes. In Fitzgeralds 1926 short story The Rich Boy, he wrote:

Let me tell you about the very rich. They are different from you and me. They possess and enjoy early, and it does something to them, makes them soft where we are hard, and cynical where we are trustful, in a way that, unless you were born rich, it is very difficult to understand. They think, deep in their hearts, that they are better than we are because we had to discover the compensations and refuges of life for ourselves. Even when they enter deep into our world or sink below us, they still think that they are better than we are. They are different.

Then, when the original version of Hemingways short story The Snows of Kilimanjaro was published in Esquire magazine in 1936, one passage read:

The rich were dull and they drank too much, or they played too much backgammon. They were dull and they were repetitious. He remembered poor Scott Fitzgerald and his romantic awe of them and how he had started a story once that began, The very rich are different from you and me. And how someone had said to Scott, Yes, they have more money. But that was not humorous to Scott. He thought they were a special glamorous race and when he found they werent it wrecked him as much as any other thing that wrecked him.

Apparently, Fitzgerald was offended by this and when The Snows of Kilimanjaro was republished in volume form the name Julian was substituted for his.

I mention this not to give this book a literary kick-off and not because Fitzgerald was another Scott, albeit with two ts; but because the book will give you the chance to make up your mind who is right Fitzgerald or Hemingway. Are the rich really different? Or do they just have more money?

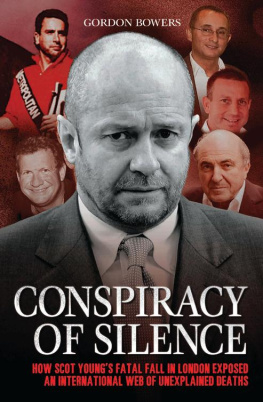

The life and untimely death of Scot Young tell us bucketloads about what it is to be rich. Although he started out poor in the backstreets of Dundee, little is known of that part of his life. His grieving parents have not spoken to the press and few who knew him then have come forward. The mystery that surrounds him now was a mantle even then.

Indeed, little was known of him even when he soared like a shooting star into the firmament of the super-rich, before coming crashing to earth again both metaphorically and, tragically, physically.

He only became known to the public when the reporting restrictions at the Family Law Court were dropped some way into what turned out to be one of the longest divorce proceedings in the history of the British legal system. In the courtroom, the figures that were bandied about were staggering. There were millions, sometimes billions, along with all the trappings of seemingly limitless wealth the diamonds, yachts, private jets, mansions, Porsches, Ferraris, haute cuisine, exotic holidays and, of course, supermodels. Not only that, he was surrounded by others of similar if not greater wealth.

Then, suddenly, it was all gone. Nobody knows where. Nobody is saying. But still Scot and his buddies seemed to continue to live the high life. They still lived in mansions or million-pound apartments, living and dying with pockets stuffed full of cash.

Scot Youngs tragically short life gives us a glimpse into another world where, perhaps, the people are different. They certainly do not have the concerns of us ordinary mortals paying our taxes and putting food on the table. They pay more for a meal that we earn in a month and can raise a mortgage that is more than you or I could earn in several lifetimes.

But are they happy? That does not seem to be a consideration. Some of them seem to be very damaged. In fact, a circle of people around Scot Young died in mysterious circumstances. As did Young himself. They were, it seems, members of a Ring of Death.

Now that Young is dead, the chink through which we observed this secret world has closed. The gilded portals of this Gatsbyesque universe are slammed shut and the survivors have closed ranks. Even during the divorce case and the various inquests, they fought tooth and nail against appearing in court. When they did, their answers were less than illuminating. Scots entire set, it seems, is infected with collective amnesia.

Nevertheless, we are in familiar territory. Young and his circle inhabited Mayfair, Knightsbridge and country houses just the places Agatha Christie and others of her ilk have led us to expect a murder, or other nefarious goings-on. Who we need on the case is Hercule Poirot. Who we have is Inspector Japp.

The plodding policemen from Scotland Yard came to the conclusion that there was nothing suspicious about the death of Scot Young, when any armchair detective knows that there is suspicion written all over it. Not only that, there are all the other elements of a crime drama. There are mysterious murders, unconvincing suicides, spies, gangsters, drug smugglers, money launderers, con-men, battling blondes, celebrities, famous chefs, glitzy restaurants and night clubs, conniving tycoons, foreign magnates, private eyes, political intrigue, jealousy and greed. Only this isnt a murder mystery; its real life.

It seems to me that enough has come out about the glittering world that Young inhabited to develop a number of plausible theories about how he met his end. The clues must all be there. It is only a question of figuring it out.

The problem is, of course, that Young himself went to a great deal of trouble to cover his tracks as he went. He hid everything he was doing in off-shore tax havens, sham companies and shell banks. Everyone he dealt with was as secretive as he was. The police, private detectives, forensic accounts, Her Majestys Revenue & Customs, bankruptcy courts, legal trustees and High Court judges have not been able to untangle the web he spun. Neither have I. But I have done all I can to lay out the evidence as straightforwardly as possible. Attempting to wrestle too much with the detail may result in not seeing the wood for the trees.

While you are trying to solve this murder mystery, dont forget to spend a moment or two to luxuriate in the lifestyles presented here that otherwise you can only dream of. Are the rich really different? You are about to find out.

GORDON BOWERS, LONDON

O n the evening of 8 December 2014 the shattered body of bankrupt property tycoon Scot Young was found impaled on the railings sixty feet below his 3 million luxury penthouse apartment in Montagu Square, Marylebone, in central London. He had suffered horrendous injuries after falling four storeys. His mutilated corpse was discovered by fellow residents at 5 pm that Monday afternoon. The police quickly screened the gruesome scene from onlookers. Firefighters had to cut through the railings with an angle grinder before the body could be removed.

It was a horrific scene, said fifty-seven-year-old Gary Sutton who was working nearby. The police were visibly shocked one said it was the worst thing he had seen on the job. It was all very distressing.

It was just as horrifying for passers-by.

I had to divert my eyes, another witness said. The police had covered the body but I could see from behind that he was on the spike because I could see his feet dangling towards the basement floor. It was horrible.

Youngs horrific death plunge seemed to have come direct from a gangster movie, where mobsters are apt to fling their hapless victims from high buildings. Even good guys such as James Bond or Sherlock Holmes at the Reichenbach Falls had been known to despatch their foes into vertiginous oblivion. But, strangely, Scotland Yard said they were not treating it as suspicious. Soon they were under pressure to change their minds.