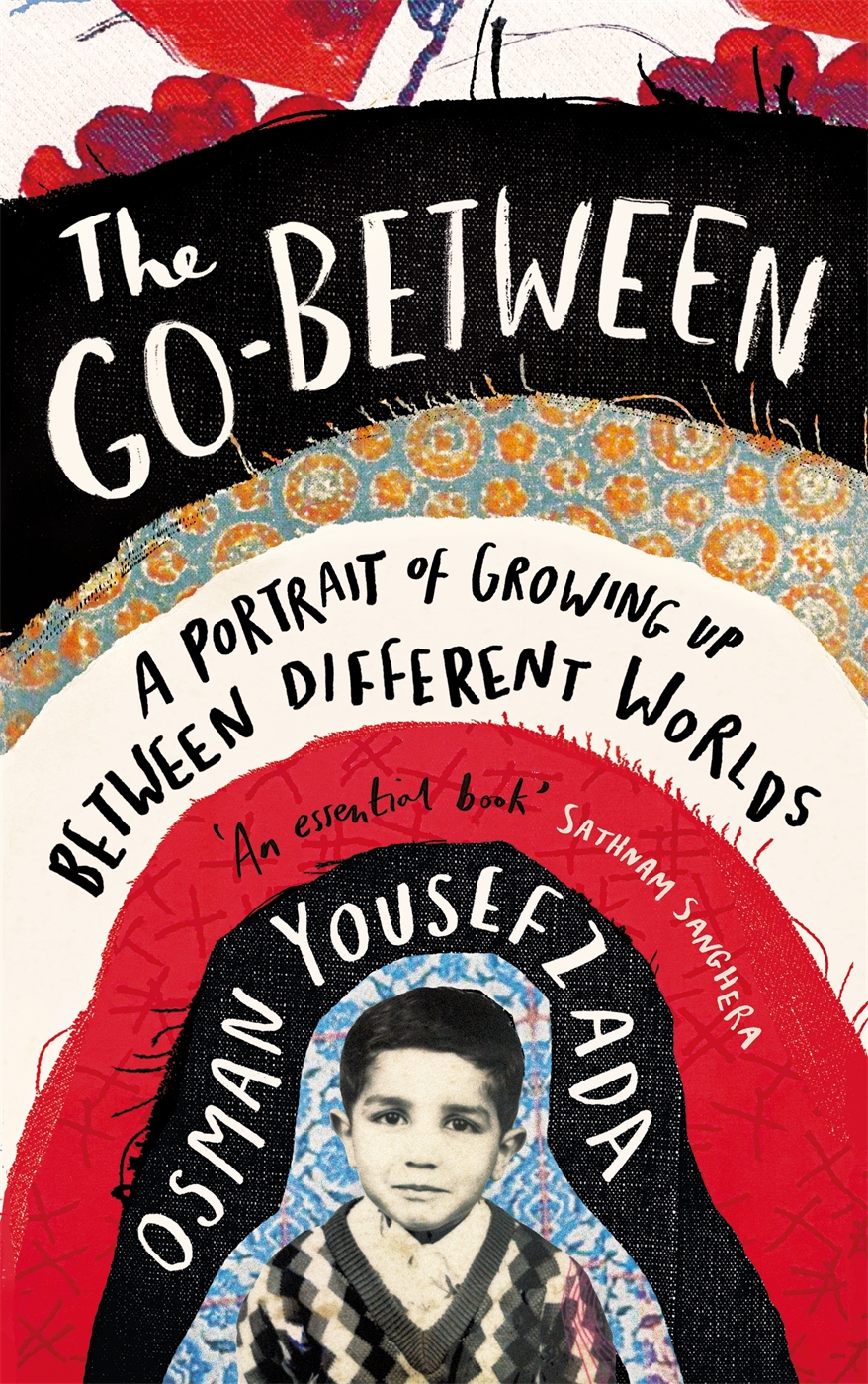

THE GO-BETWEEN

THE GO-BETWEEN

A PORTRAIT OF GROWING UP BETWEEN DIFFERENT WORLDS

Osman Yousefzada

First published in Great Britain, the USA and Canada in 2022

by Canongate Books Ltd, 14 High Street, Edinburgh EH1 1TE

Distributed in the USA by Publishers Group West and in Canada by Publishers Group Canada

canongate.co.uk

This digital edition first published in 2021 by Canongate Books

Copyright Osman Yousefzada, 2022

The right of Osman Yousefzada to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 78689 352 9

eISBN 978 1 78689 353 6

AUTHORS NOTE

The names and any identifying features of the people, places and events have been changed or merged to ensure that they are not identifiable so as to protect the privacy of individuals. This is a series of vignettes formed around my memories and my experiences and as with all memories recollection sometimes meets fiction.

I would like to dedicate this book to my mum who is beautiful both inside and out.

To my inspiring sisters who are the most powerful and strong women I know.

To my brother for his tenacity and for fulfilling his immigrant dream.

To my dad for your strength and conviction. If it was not for your voyage to England this story would have been so different.

CONTENTS

1

OUR HOOD, OUR HOUSE, AND MUMS SEWING SALON

N O. 2 WILLOWS ROAD WAS our house, with its holy green door. Down here on earth the doors of the faithful were always painted green, signifying the colour of the pure, the colour of Islam. We straddled the boundary of Balsall Heath and Moseley. It was on this street and those around it that all the immigrants Black, white, brown were housed; the prostitutes, the pimps, the broke artists and the ultra-orthodox, all searching for a better life here or in the hereafter.

Turning left at the bottom of our road, then walking south up the hill, was Park Road. Here you would see the start of bohemian Moseley, where the housing stock turned from cramped terraces to semi-detached buildings.

Eventually, youd reach the larger, detached houses around Moseley Village, with their own secret gates into a private park. This was Moseley Park, with its own lake and its own black swans, ducks, geese, moorhens and waterfowl which would promenade around the manicured lawns, then elegantly descend to swim in this magical oasis. To get inside this enchanted world, away from everyone, you needed a key: Mrs Morris, our primary school teacher, had one, and in the summer she would take us on school trips there, opening the magic door and leading us through it.

I walked through Moseley Village every day to go to school. Big, tranquil oak trees lined each street. The air was different there: you could smell the affluence the perfectly pruned privet hedges, the magnolia trees, the front drives. It always fascinated me that none of the windows had net curtains; the front rooms were open for all to see, with their mahogany dining tables, candelabras, shelves of books, cut flowers in vases and glossy leather sofas. Even their politics were on display in some of the windows: Red Labour Party posters canvassing for the long-standing Member of Parliament, Roy Hattersley.

Here lived Birminghams professional middle class the educated, the educators, the bureaucrats, many of them socialists in bucolic streets with their grand names, as if lifted from Jane Austen: Salisbury Road, Chantry Road, Oxford Road, College Road, all elegantly curved lanes that crisscrossed and meandered into idyllic tableaus at each turn.

We marvelled at how expensive and big the houses were in Moseley. My dad, Tolyar, a strong man, a man of few words, a carpenter, had fitted all the joinery for one of the larger houses in Chantry Road. It had twelve bedrooms, a drive, a garage and a granny flat. I would sometimes take Dad his lunch when he didnt feel like walking the twenty minutes home, and on occasion he would let me explore this cavernous palace. I would run eagerly into the back garden, through to the private park, follow its path that snaked around the small lake but Dad would quickly summon me back just in case I fell in.

Our own terraced house always had its net curtains drawn, never letting in the light. They hung from an immovable, tight wire and you needed to lift them up if you wanted to see who was at the door. No one could ever see in from the street, and you could just about see out.

Back then our family all lived on the ground floor of a house my parents owned. It comprised a front room, a back room, and a small kitchen-sitting room which opened up to the garden. Dad said he had bought the house from Sikhs, who had let the whole house to the Irish, and no one had cared for it. He had spent weeks cleaning it; the linoleum on the floor had congealed with the previous layers, and underneath he would count everything he cleaned: the balls of hair, human and animal, the layers of dirt, the grease and rat droppings. He had saved money, sending some back home and keeping the rest, so four years after his arrival Dad had bought a home in Englands second city Birmingham. The beds were there when he moved in. When the deal was struck, the Sikhs agreed not to charge interest on the outstanding sum, Dad always proud, when he repeated the story, of how he saved himself from hell-fire by negotiating a higher price upfront, avoiding any profane dealings with usury.

Dad now slept in his huge old double bed in the back room, which my mother, Palwashay, would also sometimes sleep in, and she had her own single bed on the opposite side of the room. My little sisters, Ruksar and Marjan, would alternate between Dad and Mums beds. My older brother, Barak-Shah, would sleep in a single bed in the front room, and sometimes, when it was too cramped next to Mum, I would join him there. My elder sister, Banafsha, would sleep on the settee in the back room.

There was a railway track at the end of our back garden, past the apple tree and the vegetable patch where my parents grew beans, spinach, courgettes and mint. Every so often trains would thunder past, and my sisters and I would stand and watch them from the fence at our gardens perimeter. They were mostly cargo trains; wagons with no windows. Occasionally there would be precious open cargo for everyone to view: fresh new cars off the factory floors at Leyland, Rover and Ford. The cars were all packed on top of each other, sprayed in countless polished colours. On these tracks you would rarely see passenger trains. None of the trains ever stopped or slowed down, but we waved at them no matter. We were explorers. We could easily hop over the small fence to pick wild blackberries in the summer, climbing up the mound towards the summit where the railway tracks sat, and wed stand there at the top, not far from the tracks, watching the trains as they rushed past, the resultant tornado pushing us back, making us unsteady on our feet.

There was an outhouse, too, in the back garden, which at one time had been a coal shed. One day I created a shrine in there, dedicated to my sisters replica Barbie, which I had bought at a local jumble sale. I had made a green Devor dress using the off-cuts from the floor of Mum and Dads bedroom, which also acted as Mums workroom. I cut three holes, one for Barbies head and one for each of her arms, sewing up the centre-back by hand. To finish it off, I made her a two-piece pink burqa out of Terylene: a coat with two holes and a popper sewn on the front to fasten it, and a square handkerchief for her hair, with ribbon strips to tie under her chin. Roxana the Barbie was enthroned on an upside-down Dairy Crest crate in which the milkman deposited the milk each morning covered with one of Mums embroidered tablecloths. Beside and in front of Roxana I laid out my offerings of tangerines and homemade cakes.