Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

Copyright 2022 by Guy Lancaster and Christopher Thrasher

All rights reserved

First published 2022

E-Book edition 2022

ISBN 978.1.43967.674.5

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022943528

Print Edition ISBN 978.1.46715.327.0

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My work is dedicated in loving memory of my mother, Theresa Thrasher (19532021).

I am grateful to my coauthor, Guy Lancaster. Guy has a unique talent for bringing out the best in writers. I do not know how he does it, but I know that I am a better writer because he does it.

I thank Liz Robbins and the entire team at the Garland County Historical Society. This book was only possible because of the encouragement, support and guidance of the award-winning Garland County Historical Society.

I appreciate Tom and Mary Hill, at Hot Springs National Park, who taught me most of what I know about Hot Springs, Arkansas.

I am grateful to Abby Hanks for her helpful comments on several portions of this manuscript.

I am thankful for my father, David Thrasher, who reads everything I publish and always encourages me to write more.

I reserve my deepest thanks for my wife, Barbara Thrasher. If I have accomplished anything as a scholar, it is only because of her constant encouragement and support.

Christopher Thrasher

This book is dedicated to my mother, Edith Lancaster, who helped keep me fed while this work was in progress, and who said she would be delighted to have a book dedicated to her, no matter how terrible the subject.

I have to thank Christopher Thrasher for undertaking this project with me. Christopher is an amazing historian with an attention to detail and dedication to nuance that have proven inspiring to me again and again.

My friend Michael Hodge got me started on this particular line of inquiry, and Ill always be thankful to him for that. Let me second Christophers praise of the Garland County Historical Society, which is truly one of the best county historical societies in the state of Arkansas and one dedicated to bringing the full fruits of historical inquiry and preservation to the local community.

This manuscript has undergone multiple visions and revisions, and I must thank everyone who has provided feedback on any of the various versions. Too, the Arkansas State Archives and the Butler Center for Arkansas Studies at the Central Arkansas Library System have worked to make access to state newspapers easier through projects of digitization, which greatly facilitated the writing of this book.

And finally, I am perpetually indebted to my wife, Anna, whose sweet love remembered such wealth brings, that then I scorn to change my state with kings.

Guy Lancaster

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

Up with the kettle

And down with the pan

And give us a penny

To bury the wren

Traditional Irish Wrens Day song

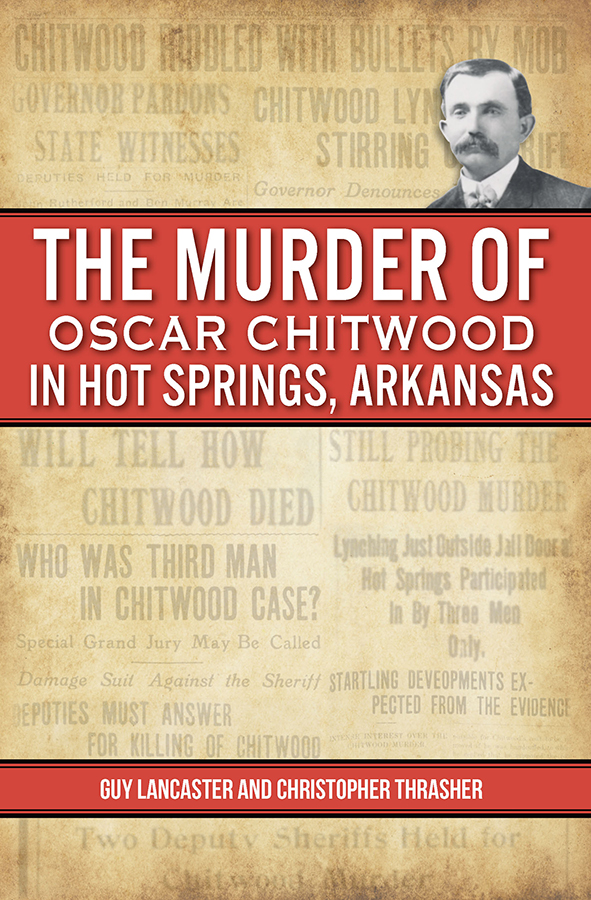

Oscar Chitwood was lynched, to begin with. There was no doubt whatever about that.

At least, for a few days. But soon enough, the story of the mobthat, the world had been told, came and shot Oscar Chitwood to death on December 26, 1910, there at the county courthouse in Hot Springs, Arkansasutterly fell apart. As much as locals wanted to believe Deputy John Rutherfords claims on this matter, all the evidence rather too convincingly argued the contrary, and so in 1911, Rutherford and another deputy, Ben Murray, were indicted for the premeditated murder of Chitwood.

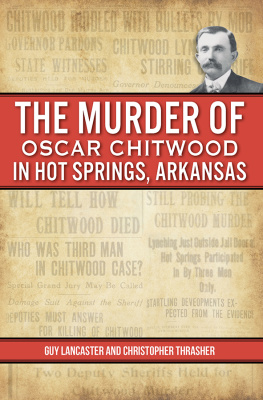

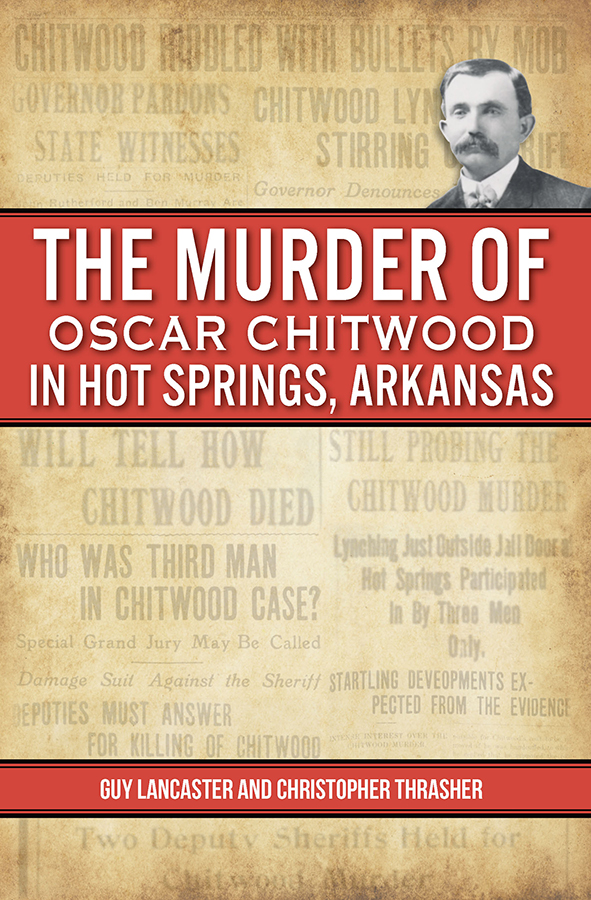

Granted, Chitwood would have been a likely candidate for a lynching. He was a white man living in the South at a time by which the practice of lynching had largely hardened along racial lines, but white men were still occasionally executed by vigilante mobs in this time and place, especially when they were held responsible for the death of popular lawmen, like Sheriff Jake Houpt, whose image graces the cover of this book and who had, earlier in 1910, been killed in a shootout with Oscar Chitwood and his brother, George. But the young outlaw did not die at the hands of any mob. There is little doubt whatever about that.

Front page of the December 26, 1910 Vicksburg Evening Post.

This fact did not stop Oscar Chitwoods name from appearing on many nationally circulating lists of lynching victims. Typically, organizations that assembled such lists, like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Tuskegee Institute, based their work on nationally circulating newspapers. The initial story of the lynching of Chitwood did spread nationally, but those same newspapers did not follow the subsequent developments, the doubts and, later, the indictments, and scholars basing their work on these inventories have unwittingly included the Chitwood murder as an example of white-on-white lynching even well into the twenty-first century.

But what, though, was the real difference? Policemen had rather coyly been involved in lynchings previously, be it by informing mob leaders when a prisoner was expected to be transferred or by turning over the keys to the local jail after members of the mob made the necessary pretense of surprising the lawman on his rounds and holding him at gunpoint. After the fact, many of these policemen claimed to recognize no one from the mob, even if the lynching happened in the full light of day and the mob went about its task unmasked. The historical record is replete with lynchings that were facilitated by, at a bare minimum, the inactivity of sworn officers of the law at crucial points in time.

However, policemen coldly perpetrating a 2:00 a.m. assassinationand making such a hash of things that even those who would have been glad to be rid of Chitwood could not fail to notice certain discrepanciesseemed a bridge too far for many. The official push toward something like justice was probably aided by the less-than-stellar reputation of local law enforcement, the late Sheriff Houpt excepted, due to a whole history of corruption and double dealing that made Hot Springs a byword even in a state like Arkansas. One can easily imagine that, had Deputies Rutherford and Murray but covered their tracks just a little better, the history books would record Chitwoods killing even today as one more tragic enumeration of a form of violence so decidedly American. But this was not meant to be.

And there are lessons for us in that.

As reported in the September 26, 1922 edition of the Sentinel-Record newspaper in Hot Springs, Judge Scott Wood of the local circuit court, while overseeing a grand jury investigation of alleged vigilantes, issued the following defense of the tradition of law and order over and above the sort of justice meted out by men in secret conclave, such as the Ku Klux Klan: If the courts and juries should approve or palliate the use of unlawful means to promote the public good, public good would soon be merely the pretext for the use of all kinds of unlawful means to carry out the arbitrary will of an organization, which would usurp the powers of government and substitute its dictum, its night riders, its tar and feathers and its whip for the dignified and orderly processes of the courts of this country. The judge also cited a contemporary incident in Shreveport, Louisiana, in which a number of negroes working in the railroad shops received notices purporting to be from the Ku Klux Klan, that they must quit work, that the Klan only warned once and if their warnings was not obeyed their punishment would be inflicted on the offender. Although, as Wood notes, the Klan denied responsibility for the affair, this incident demonstrated that the organization cannot exist without having designing persons use the terror which it inspires to satisfy their own petty grudges and desires.

Next page