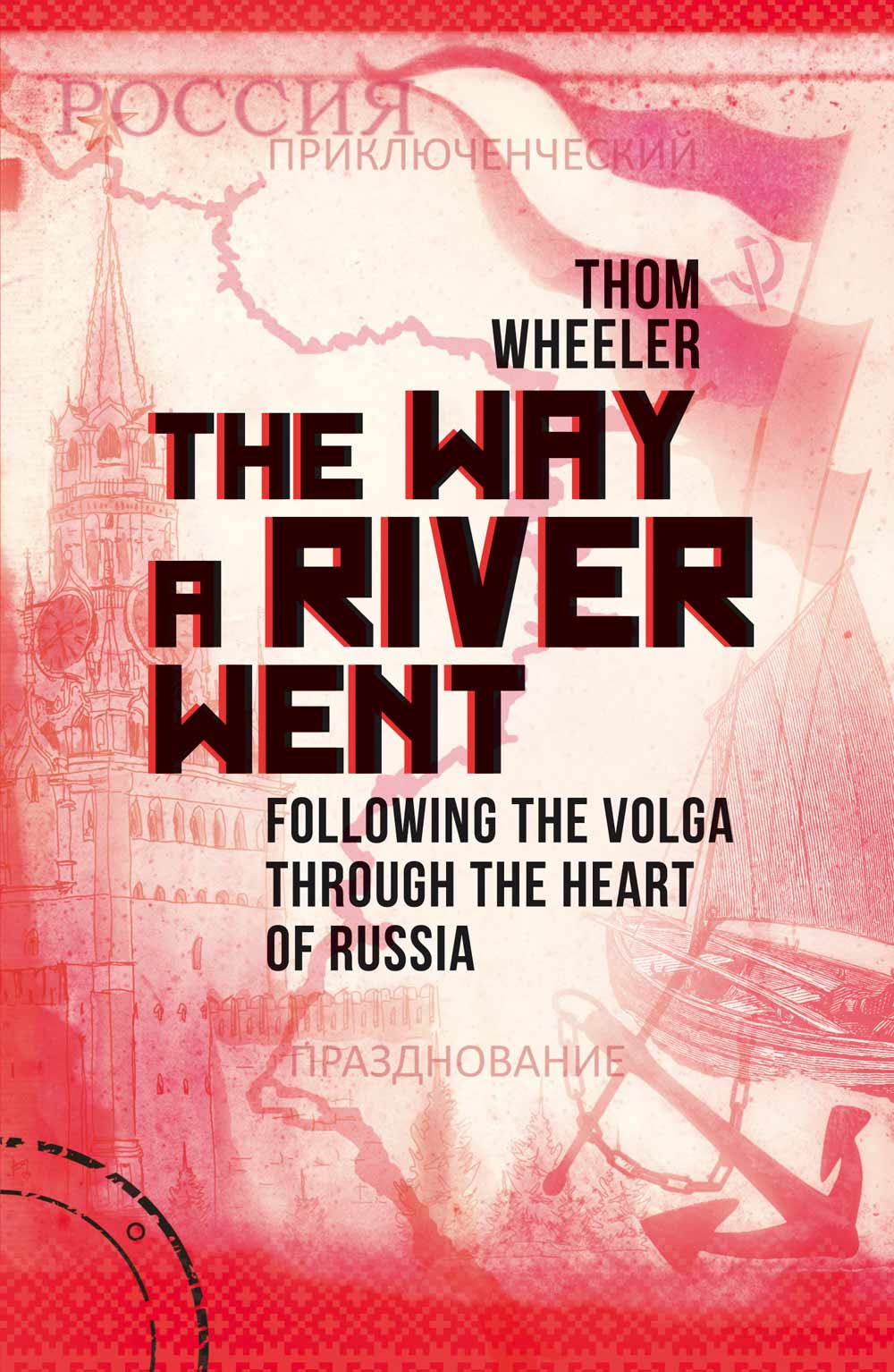

THE WAY A RIVER WENT

Copyright Thom Wheeler, 2015

Cover images IR Stone, Liudmyla Marykon, Irmairma, lynea, Robert Biedermann, Natalia N K, Veronika Surovtseva/Shutterstock

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced by any means, nor transmitted, nor translated into a machine language, without the written permission of the publishers.

Thom Wheeler has asserted his right to be identifi ed as the author of this work in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Condition of Sale

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Summersdale Publishers Ltd

46 West Street

Chichester

West Sussex

PO19 1RP

UK

www.summersdale.com

eISBN: 978-1-78372-629-5

Substantial discounts on bulk quantities of Summersdale books are available to corporations, professional associations and other organisations. For details contact Nicky Douglas by telephone: +44 (0) 1243 756902, fax: +44 (0) 1243 786300 or email: .

To R. M.

'It is pleasant to have been to a place the way a river went.'

Henry David Thoreau

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

LOVE IN A BIG MUSEUM

I met Vicky Marshall when I was six years old.

Leonid Brezhnev was at the peak of his powers as General Secretary of the Communist Party. I was in the midst of my idyllic and carefree childhood spent tucked away on a small farm in a small hamlet in Dorset with my sister and parents. Along a narrow, stony path that crossed a trickling river before winding through a shady wood of crab apple and hawthorn, our closest neighbours Eric and Edna lived and grew rhubarb. Huge pink and green bundles would appear in our kitchen come the summer, announcing months of crumbles, fools and anything else you could do with a stick of rhubarb. Every year Eric and Edna's granddaughter came to stay with them. Vicky had long blonde hair as straight as uncooked spaghetti and for a while I was in love with her. Or so I thought, but probably more in love with the bike with a crossbar that arrived with her. Hours were spent careering up and down the gravel track on the bike with a crossbar. Her visits were a much anticipated event during those early years at Walnut Farm, until to my complete delight she came to live with her grandparents permanently.

When not at school, our free time was spent enjoying escapades in the great outdoors that surrounded us. The spring and summer months were joyous for us as the adults laboured over the harvest, picnics and home-made wine bringing people together. The barns lent themselves to our fervent imaginations as we spent hours manoeuvring heavy bales to make tunnels and dens, relatively complex structures that allowed us to hide away from the outside world. They survived intact until gradually deconstructed for the needs of cattle and horses with the onset of autumn and then winter.

Whilst we continued to rampage through our blissful childhood, the Cold War was at its height, the Soviet Union powerful and threatening to the outside world yet increasingly rotten on the inside as the Brezhnev years took their toll. By the Moscow Olympics of 1980, Soviet relations with the West were at an all-time low, and one September day that same year our childhood together ended as I was sent off to a new school and Vicky dyed her hair scarlet.

Two words heard nearly as often as Depeche Mode on Radio One during that period were perestroika and glasnost. They were to define Mikhail Gorbachev's reign as leader of the Politburo and the final days of the Soviet Union. Glasnost was a policy introduced by Gorbachev, who had quickly succeeded Brezhnev's successor Andropov, which called for increased openness and transparency in government institutions and the activities within the Soviet Union. Gorbachev believed it would help reduce the corruption that had raged during the seventies and was still fervent at the highest levels of the Communist Party. Perestroika was a policy of reform that had been proposed by Brezhnev and embraced by Gorbachev, with the ambition of creating a greater awareness of markets and bringing to an end central planning. A policy more than likely very much needed rather than desired after the country had been bled dry by corruption.

I became increasingly interested in the flailing Soviet project whilst Vicky was becoming more interested in things closer to home. Her particular reaction to the safety of her upbringing had kicked in fairly early in her teenage years. To a soundtrack of the Cocteau Twins and Siouxsie and the Banshees she had backcombed her hair and forced her legs into drainpipes before my voice had broken. She had been sent home from a summer camp for sniffing aerosols before J. R. had been shot and 'Relax' T-shirts were a fashion musthave. Well before her fifteenth birthday, I had awkwardly encountered her fumbling around in the back of a steamedup Ford Escort estate parked up outside the front gate. She was top of her class and good at sport, my best friend that I was proud to have. By the time she was eighteen she had her first proper job as a receptionist at a local firm of solicitors; she wasn't interested in university she wanted to earn money, rent a flat and buy a car. By adulthood she had expurgated her need to be different and thus marched forward to join the rat race. However, whatever she might have believed and acted upon at the time, she was always destined to be different.

I don't remember seeing very much of Vicky during our twenties: our lives took different paths. Christmas perhaps, and birthdays, but beyond that we would come together very seldom. We had become quite different people with very different outlooks on the world. She had come and gone from a handful of jobs, though she was always in work, always self-reliant and independent. Men came and went, until eventually 'the one' turned up. They got married but it didn't work out and they were acrimoniously divorced within three years. He hadn't been the one after all.

Around the time of Vicky's divorce, I had been putting into action a rather ill-conceived project. I had become a self-styled tour operator, taking people on holiday to Russia. I'd stitched together a handful of tours, ranging from sixteen days crossing the heartland of Siberia to a long weekend in St Petersburg. Having tried them all out myself, I found it inconceivable anybody else wouldn't enjoy them and pay me a substantial amount for their enjoyment. I liked being a tour operator. I just wasn't very good at it.

I had gone into the venture quite unprepared. However, early on it had become clear that I would have to make a small concession to the illusion of professionalism. This took the form of acquiring a licence from the Civil Aviation Authority, the governing body for all things involving fully protected and legit travel to foreign parts. Anyone who wanted to be considered competent had to be licensed.