1

TESTIMONY

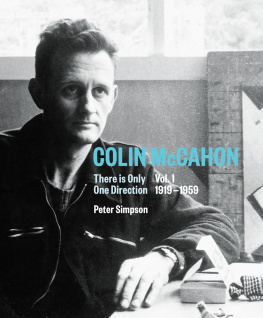

M Y ENGAGEMENT WITH C OLIN M C C AHONS WORK BEGAN when I was very young and has lasted a long timeyou might say a lifetime. It was initiated by a picture of his given to my parents at the time of the birth of my eldest sister in Dunedin in 1948. The gift came from McCahons own sister, Beatrice Parsloe, who with her husband Noel was a friend and colleague of my parents, at that time both training to be teachers. This painting for children hung in the bedroom I shared with various of my sisters while I was growing up; and remains among the earliest of my visual memories. Of all the things that were up on our wallsprints of works by van der Weyden, Vermeer, Gauguin, van Gogh, Berthe Morisotplus a few originals by other, mostly unknown, New Zealand artistsIvy Fife, Noelene Bruningit is the one that claimed me first and has never really let me go. This despite the fact that I did not know who had painted it until many years later.

It is a small painting, perhaps 30 by 40 centimetres, in a plain wooden frame, made from black ink and watercolour in predominant shades of ochre and red. When I look at it nowor rather, when I look at the photograph I haveit is so heartbreakingly familiar that I do not quite know how to begin to describe it nor truly to understand why such a description should be necessary; for it seems to be one of those things of the world, like rain or light, that are elemental. I must have looked at it hundreds of times; I must have spent very many hours with it. It was there on the wall when I went to sleep at night and there again when I woke up in the morning.

The modest size and overwhelming familiarity of the picture have not however banished from it certain mysteries and it is these, along with subject matter of intrinsic interest to a child, that have kept me looking at it over so long a time. For instance: the four steam trains coming and going through tunnels and over bridges, each with their plume of black smoke and their line of coaches or trucks, are using the same railway line. How then will they not collide? The one arriving from the back of the picture, out of a dark aperture in the distant hills and across the long rickety viaduct, must encounter, head on, the nearer train just exiting the tunnel on the right and crossing over a much shorter, much higher, viaduct to enter a second tunnel on the opposing bluff. Or will it? You cant actually see behind the bluff where they will meet so perhaps there is another way?

This potential cataclysm, held forever in suspension, filled me with a childhood anxiety that I can feel the ghost of still. It is a central insight into painted worlds which because frozen are, like the melodist on Keats Grecian urn, for ever piping songs for ever new. Another, as enduring, is the mystery of the open sea beyond the harbour, beyond the flanking hills, beyond that stark horizon line... there are three ships, each, like the trains, with their plumes of smoke, sailing in from that far sea towards the harbour mouth, where a lighthouse stands and throws a cone of yellow light out of the picture to the left. Two mysteries, each without resolution: what is over this horizon? And why, in the broad daylight that suffuses the rest of the picture, is that bright beacon shining on the lighthouse tower?

In the sky above a yellow and green hot-air balloon floats; the balloonist trails from the basket a white handkerchief and in my childhood innocence and self-obsession I always imagined it was to me that he was waving. Three single-wing, single-propeller, pinkish-red aeroplanes fly in formation towards this aerial balloon, approaching dangerously close to its doped, surely flammable, fabric. Two more biplanes, mere black crosses on the sky, are disappearing over that far and eternally mysterious horizon going, I now think, to Peru. And there, on the highest hump of the most distant hills, is a twin-antennae radio tower with its fine aerial braided from spire to spire, picking up from the empyrean what signals?

So much for the background; in the foreground the mysteries, while no less intense, have a certain domestic, even intimate, flavour. We are looking down the S-bend of a river or an arm of the sea, flowing away from us. On the left bank stands, among poplars and pines, a childs drawing of a house, with two windows and a door making a face at the front, a smokeless chimney in the roof and a curving path up to the door. Next to it is a washing line with clothes pegged on it and in the water out the front people are swimming. One two three four five and then a sixth upright in the shallows; but one of those swimming might be a dog. The peg basket sits on the ground beside the washing line, its cloven wooden pegs no doubt within; theres a fence not far away and bush beyond.

Three yachts sail out on the water and more people are swimming, and one fishing, on the other banktheyre really just dots. A road runs along the shore with buses, cars and trucks coming and going upon it. The railway line is built above the road, looping through tunnels in the six soft ridges of yellow hills descending to the water. If anything gives the authorship of the painting away it is the hills, because they recur in so many of McCahons Otago paintings and are famously seen in the epochal, early, Takaka: night and day (1948); but I knew nothing of all that then. A railway station huddles under the lee of the nearest of these ranked hills, with sidings and a small shunting yard and, I used to hope, a signal box in which potential collisions were daily averted. Houses stand atop three of the hills, two with smoking chimneys and the smokeless one in between with a poplar and a palma titi or cabbage treeattendant.

And then, in the immediate foreground, the chief glory of the painting. Here a brick causeway has been constructed to run over the road and across the water. The train upon it has a smart black engine with red trim, four red coaches with black windows, five trucksone for cattle, one for coal, one for fuel oil, one with a tarp upon it and one for gravel to spread on unsealed roads. In the guards van that brings up the rear there is a guard who will, like the balloonist, surely wave to any small boy watching the train go by. Last of all, on the right, is a car just exiting the hoop made in the train bridge for the road; and to the left, directly under the first carriage, down there in the water with the clang and the thunder of the train going bya rowing boat with some lucky fellow idling at the oars.

I SUPPOSE NOW THAT WHAT IS MOST BEGUILING ABOUT THIS painting is the way, amidst all that activity, it mixes exotica with ordinariness. Its main subject is trains and in all the towns of my childhood we saw and heard trains go by every day. And, no matter how often we saw them, they never lost their interest, a part of which was their sheer power and terror, and another part the commonplace, the humdrumwho or what they carried, where they were going, why. It is the same with the many forms of road transport in the picture, though here perhaps the humdrum persists more tenaciously than either power or terror. Top-dressing planes we knew but hot-air balloons, not. All the extraordinary paraphernalia of the ocean, both the things that stood beside it and those that went across it, came to us only on holidays, since we lived inland, far from the sea, or as far from the sea as you could get in our skinny island.

For me, the woman who has hung out the clothes and then gone inside leaving the peg basket sitting on the ground beside the pole that holds up the wire of the washing line was my mother, just as the man driving the car through the inverted U beneath the railway bridge was my father. I could easily imagine him coming out the front of the picture, going round behind and then re-entering at the left to bump up the drive to the little house. And if this was so then those five, or six, figures in the water were undoubtedly myself and my sistersand maybe our dog, Tip. The plumes of smoke, too, had an aching familiarity. Every house we knew, in winter at least, had one issuing from its chimney; as did the steam trains passing behind the school on the branch line to Raetihi and the Limited Express going up and down the Main Trunk Line every night of our lives.