One

ORGANIZATION AND OPENING OF THE EXHIBITION

The first worlds fair, the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nationsbetter known as the Crystal Palacewas held in London in 1851. Built of iron and glass, the exhibition facility covered more than 20 acres. The fair was a great success, netting more than six million visitors and a $750,000 profit. It is no wonder, then, that this success begat a tradition of subsequent fairs.

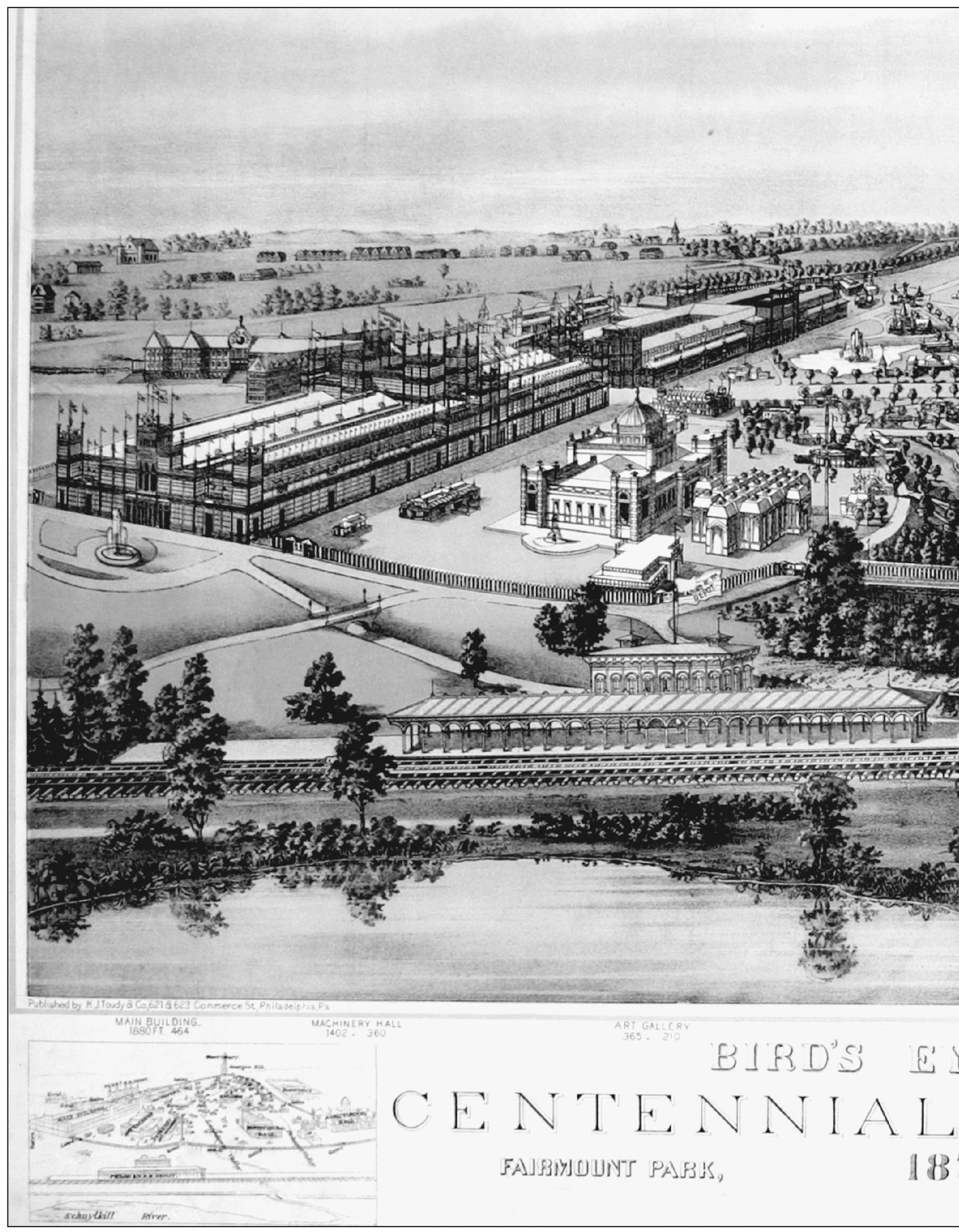

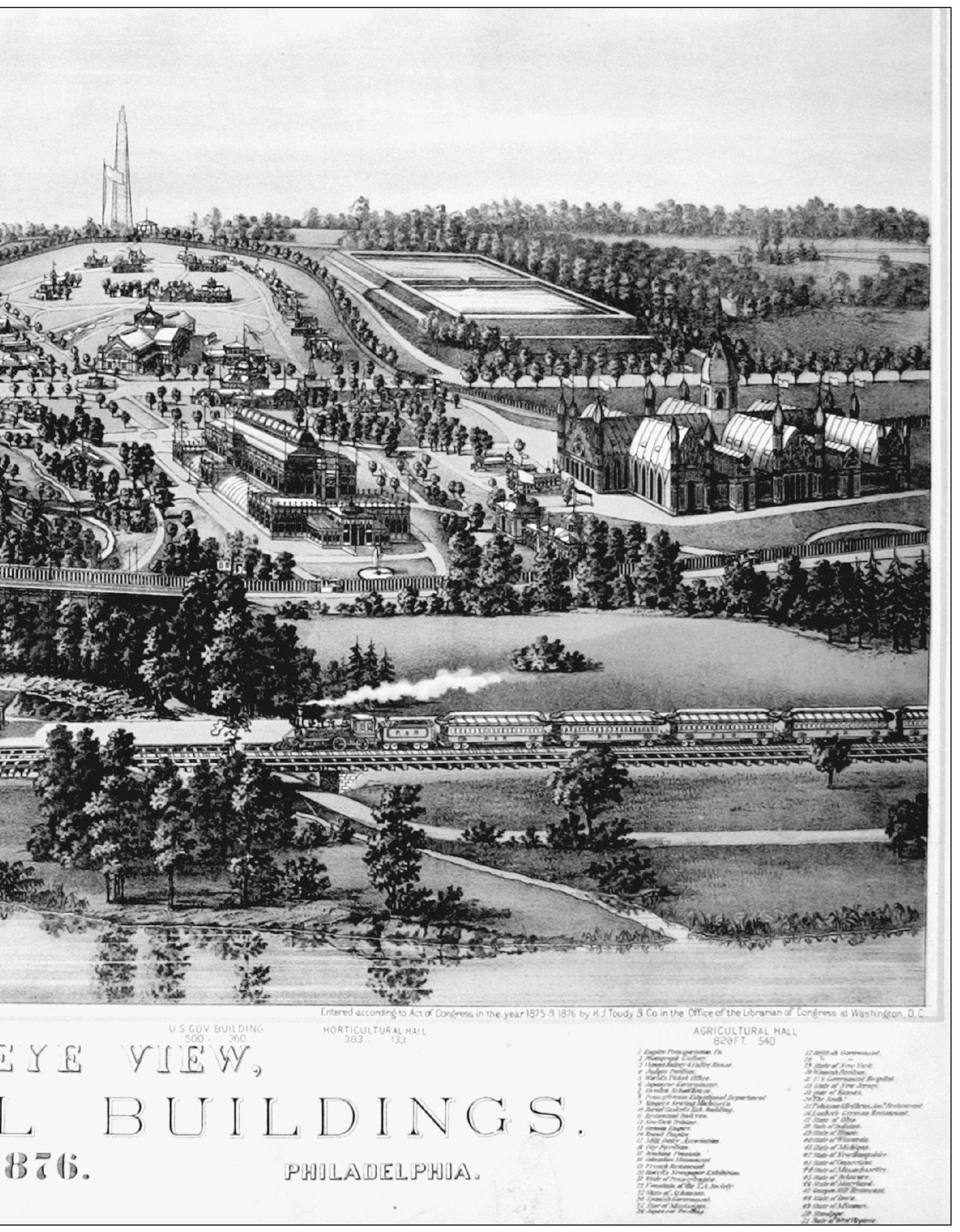

America held its first worlds fair, also called the Crystal Palace, in New York in 1853. The iron-and-glass structure built for that exhibition represented a feat of American engineering, where laborers assembled prefabricated parts to complete the whole. The building covered 170,000 square feet. Unlike the London fair, the exhibition held in New York ended in failure for a variety of reasons. The tradition of fairs continued at subsequent European venues but did not return to American shores again until 1876. Host city Philadelphias decision to build five main exhibition buildings, as well as the additional state, federal, foreign, corporate, and public-comfort buildings, represented a departure from previous fairs that relied exclusively on a few large buildings. It set the standard for fairs to come.

Once exhibition organizers had settled on the themes of patriotism, American industrial prowess, and the unification of the United States, the members of the Centennial Commission worked doggedly to raise funds and, based on their visit to Vienna International Exhibition in 1873, to improve the transportation infrastructure for traveling to the Philadelphia fair. The railroad lines that provided passenger service to the exhibition included the Pennsylvania Railroad; the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad; the North Pennsylvania Railroad; the Philadelphia, Wilmington, and Baltimore Railroad; the West Chester Railroad; the New Jersey Southern Railroad; the Camden and Atlantic Railroad; and the West Jersey Railroad. Two principal steamship lines serviced Philadelphia and European portsthe American Steamship Company (with weekly sailings) and the International Steamship Company (or Red Star Line), which traveled every two weeks. Despite the increased capacity of transportation lines, the throngs of visitors overwhelmed the system. Further, the entry of travel agency Cook, Son, and Jenkins into the tourist market threatened the business of rail agents and provoked severe competition between them.

Getting to Philadelphia was just the beginning of the adventure. Rail agents partnered with the Centennial Lodging House Agency to enhance the travel experience. The city boasted an availability of more than 300,000 lodging spaces; the Centennial Lodging Company controlled 10,000 of these rooms and held options on another 50,000 per day. The Centennial Transfer Company and trolley lines carried passengers to and from the fair. Paying 50 to enter the grounds, visitors used a series of transportation methodsrolling chairs, an elevated railway, and walkingto navigate the grounds. Guidebooks, both official and unofficial, suggested one-day to fourteen-day itineraries for seeing the fair. Throughout the grounds there were restaurants, public-comfort stations, and soda and water stands that offered some refreshment to the weary, but enthusiastic, travelers. Many visitors grew tired and frustrated, such as Mark Twain, but most attended the awe-inspiring displays with passion and enthusiasm.

BIRDS-EYE VIEW. This view of Fairmount Park underscores an impressive worlds fair landscape that encompassed 5 main buildings and 250 additional structures.

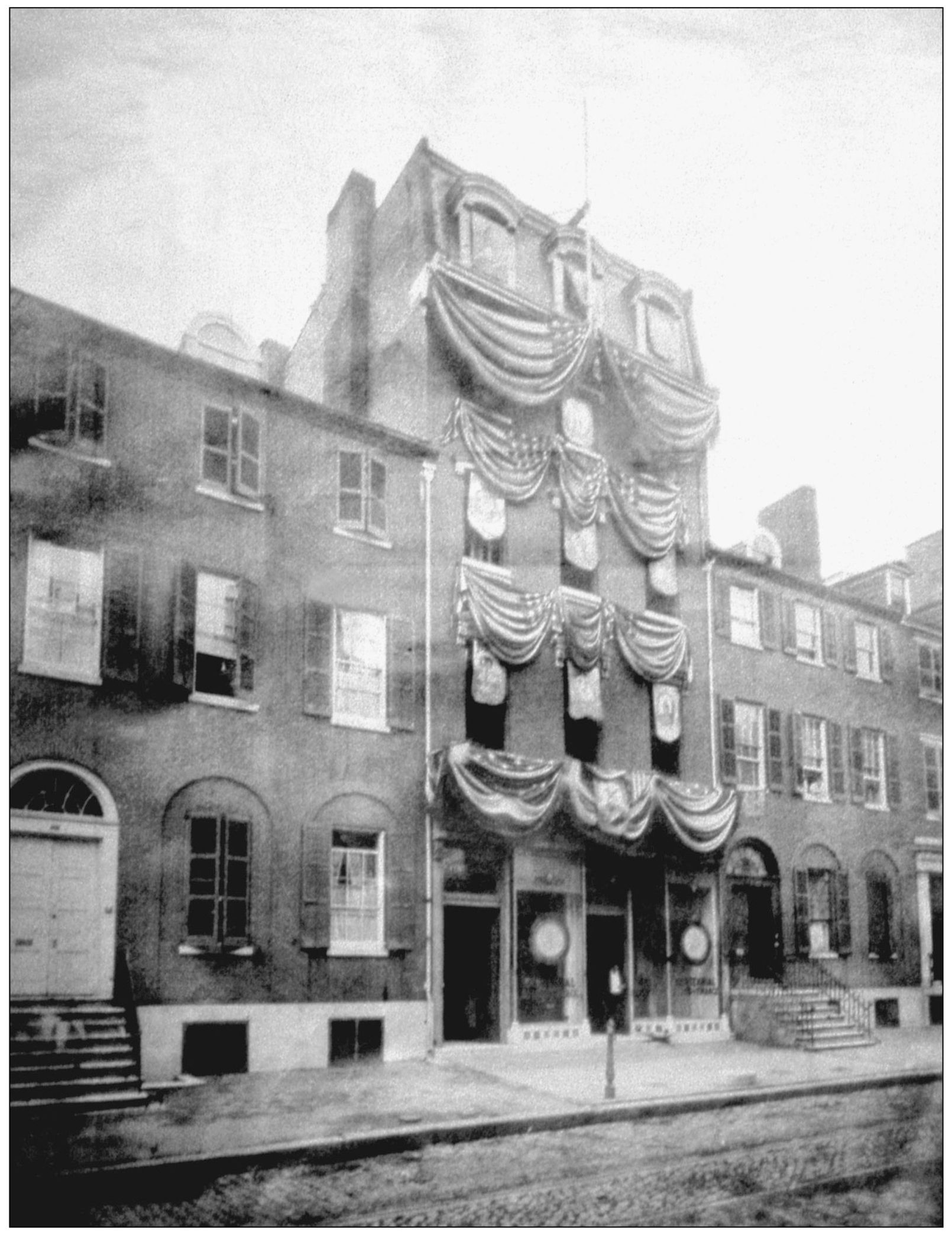

U.S. CENTENNIAL COMMISSION HEADQUARTERS, 904 WALNUT STREET, PHILADELPHIA. Following the end of the Civil War, Americans began to prepare for the celebration of the nations 100th birthday in 1876. The Pennsylvania legislature nominated Philadelphia as the location for an international exhibition. A bill adopted by Congress on March 3, 1871, created a commission composed of one delegate from each state and territory in the Union. The U.S. Centennial Commission, charged with the oversight of the planning, construction, and operation of the exhibition, held its first session on March 4, 1872.

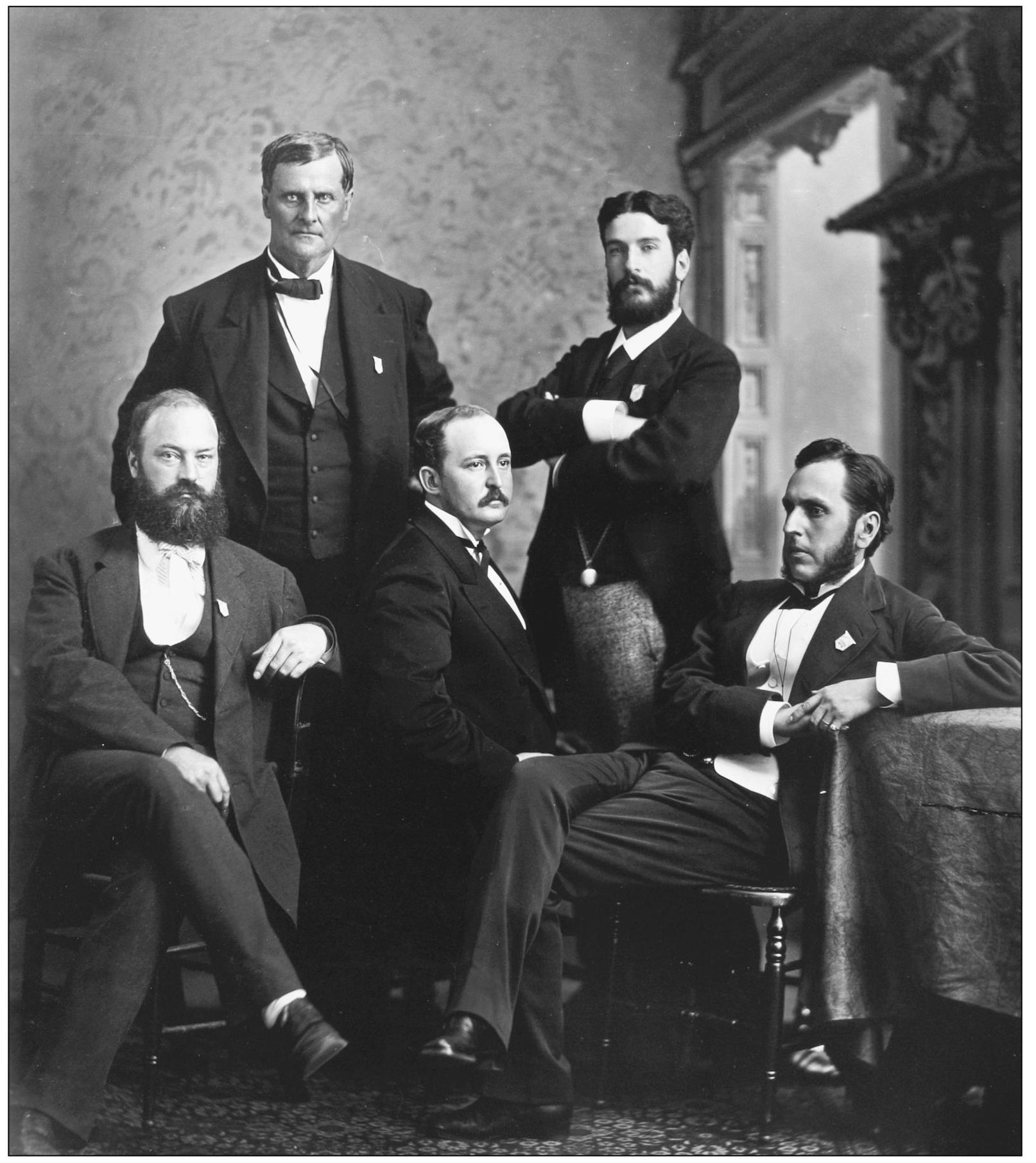

OFFICERS OF THE U.S. CENTENNIAL COMMISSION. H. J. Schwarzmann, the chief architect of the exhibition, appears at the upper right of the photograph. The other men in the photograph are (to the best of the authors knowledge), clockwise from right, John L. Shoemaker, solicitor of U.S. Centennial Commission and Board of Finance; Francis A. Walker, chief, Bureau of Awards; David G. Yates, chief, Bureau of Admissions; and Capt. John S. Albert, superintendent of Machinery Department and Building.

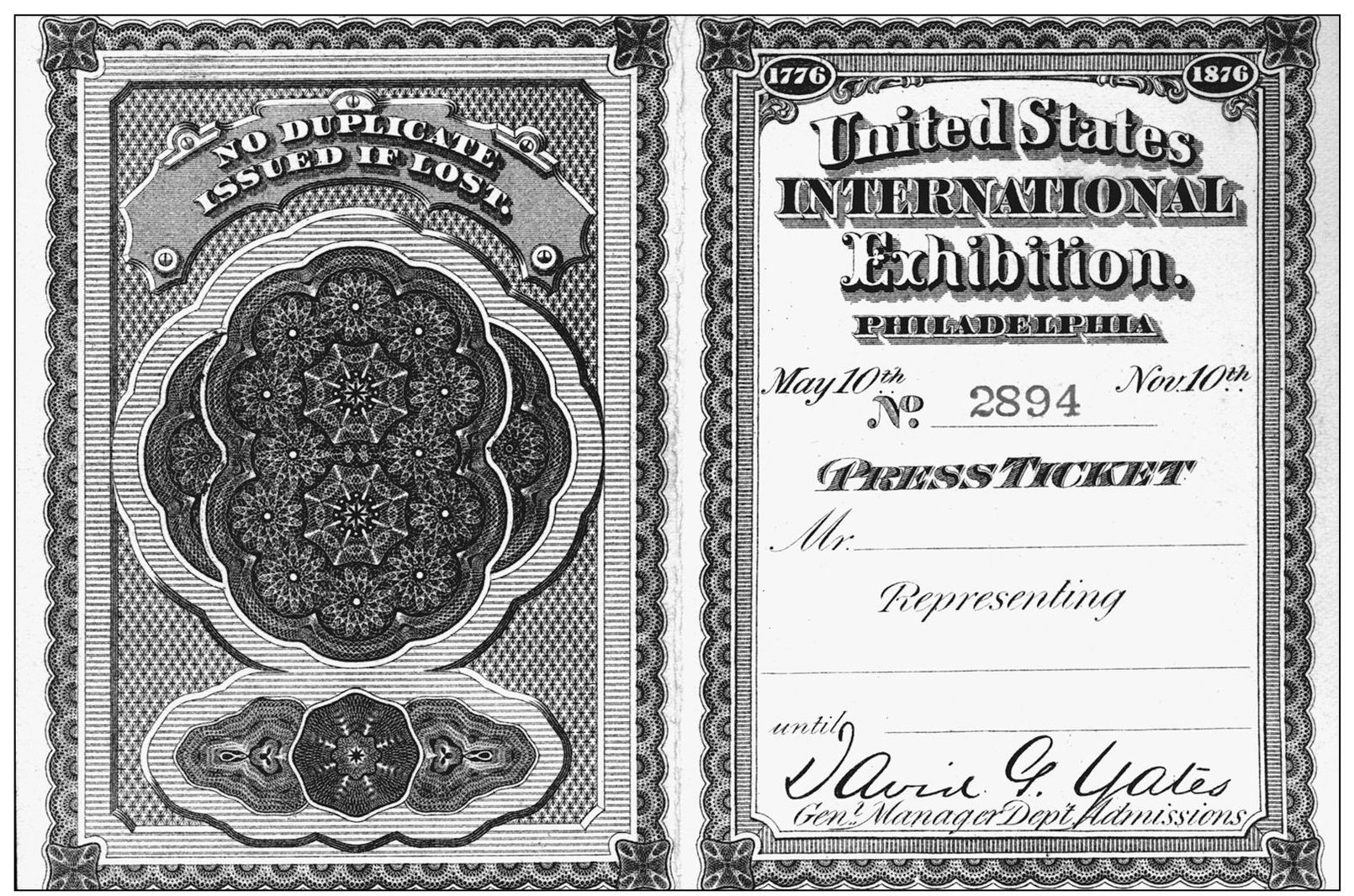

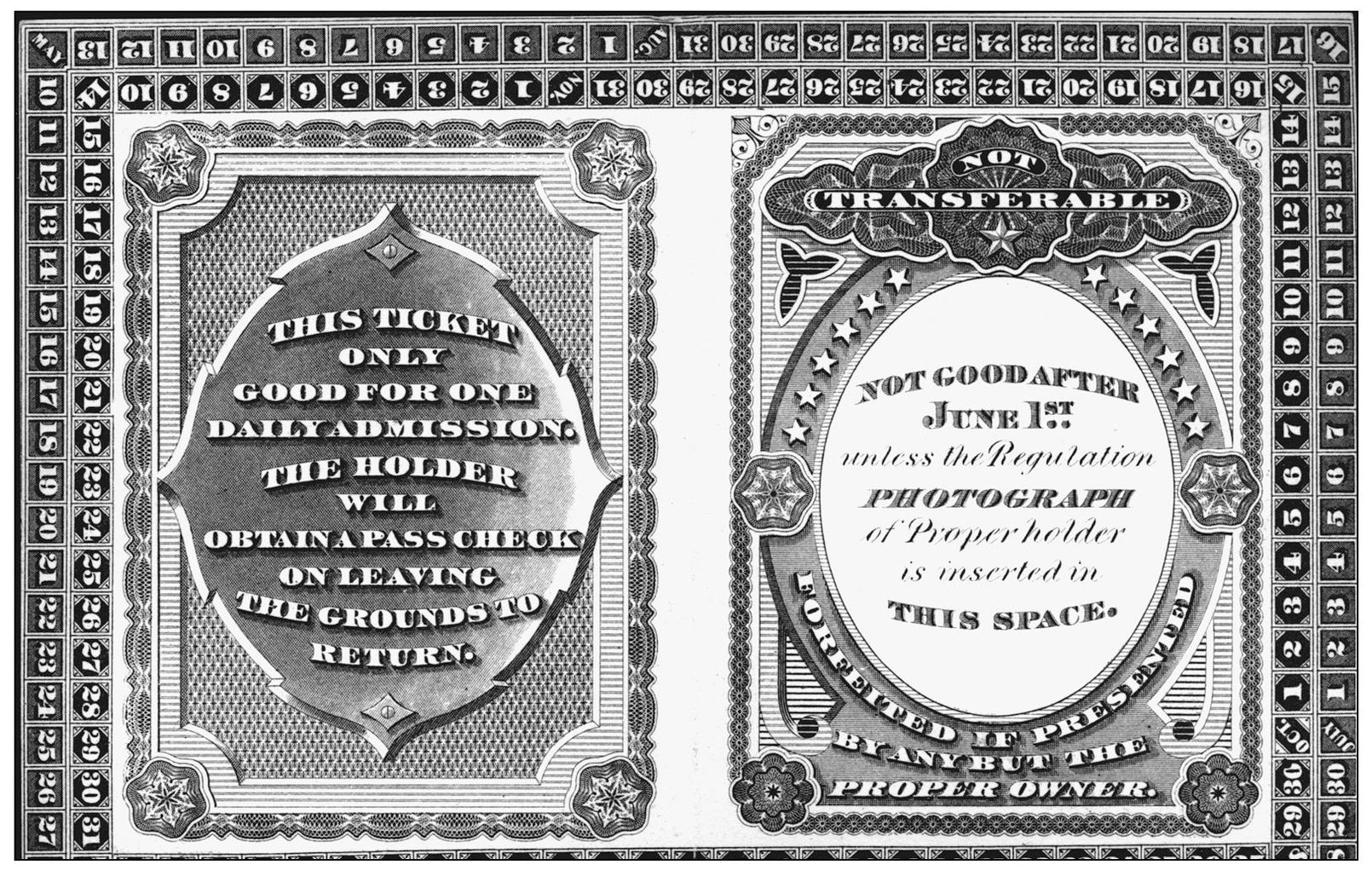

PRESS TICKET, FRONT. The headquarters for the press was located in the Public Comfort Building. A large hall was outfitted with tables and chairs for the use of the army of correspondents and reporters who were engaged in making the attractions of the exhibition known to the public.

PRESS TICKET, BACK. The Centennial Exhibition also included the American Newspaper Building, which housed copies of more than 8,000 newspapers published in the United States. Visitors were invited to sit in one of the many chairs and sofas in this building to read the local papers from their home states.

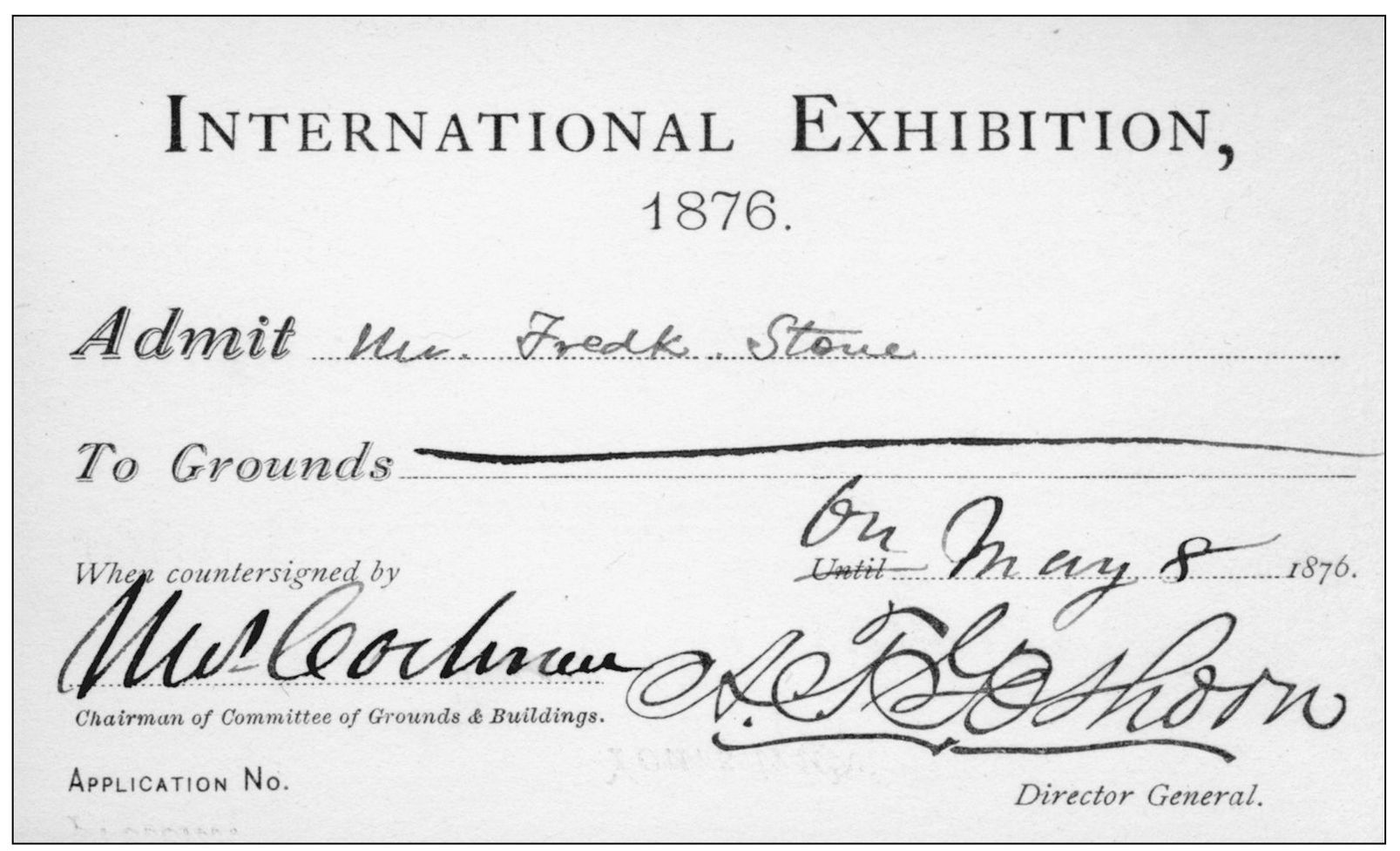

INTERNATIONAL EXHIBITION TICKET. Admission to the Centennial Exhibition was 50, payable only in paper currency. Transfer tickets were issued on request for cattle exhibits held outside the enclosed fairgrounds.

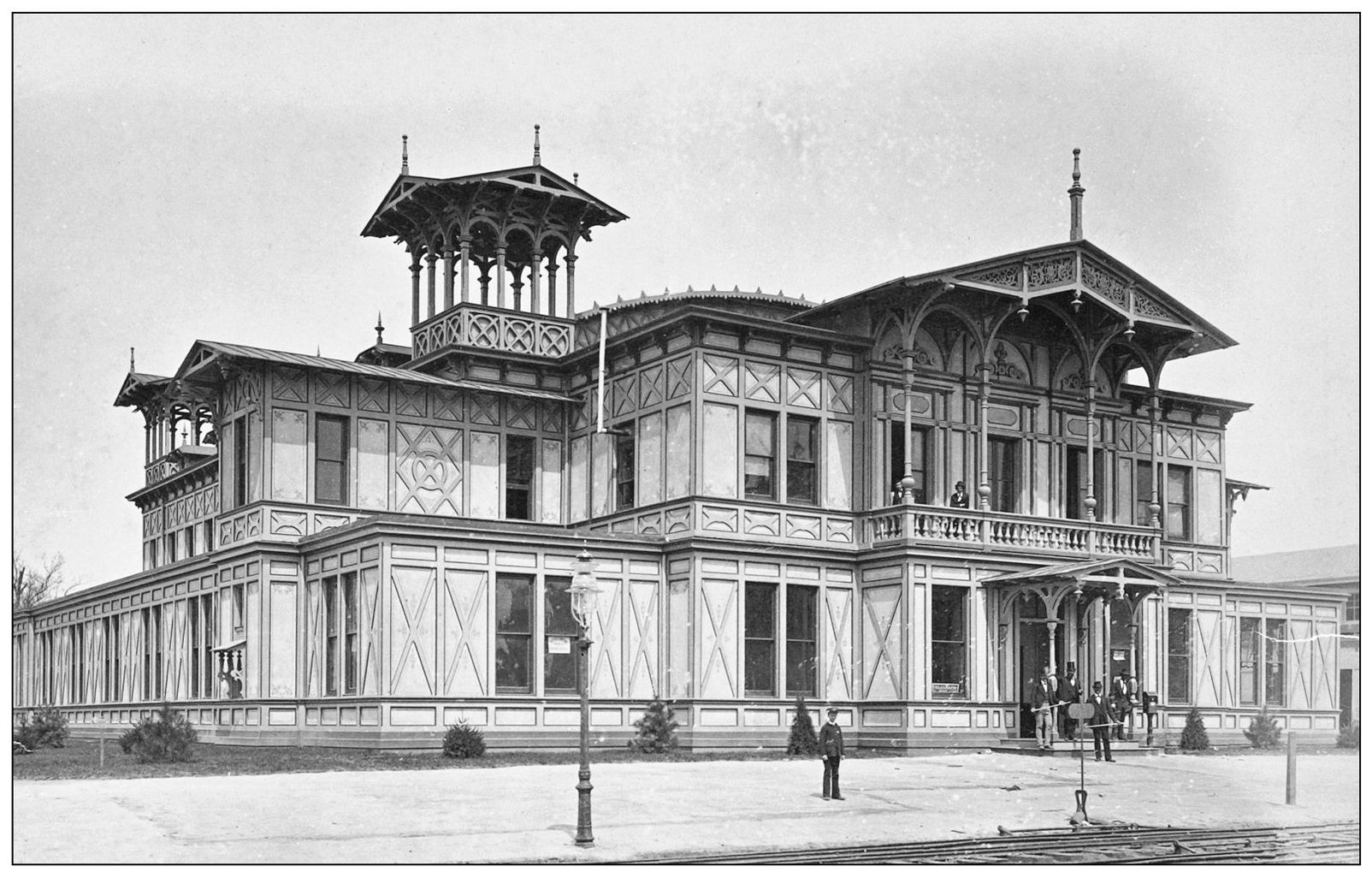

JUDGES HALL. Awards given to exhibitors were identical bronze medals. The Victorian fascination with order led to a system of classification for exhibited objects so that they could be cataloged, examined, and judged. Geologist William Blake first proposed the categories used to organize the exhibits at the Centennial Exhibition. This notation system was the foundation for Melville Deweys decimal-based arrangement of books, which was first published as a pamphlet in 1876.