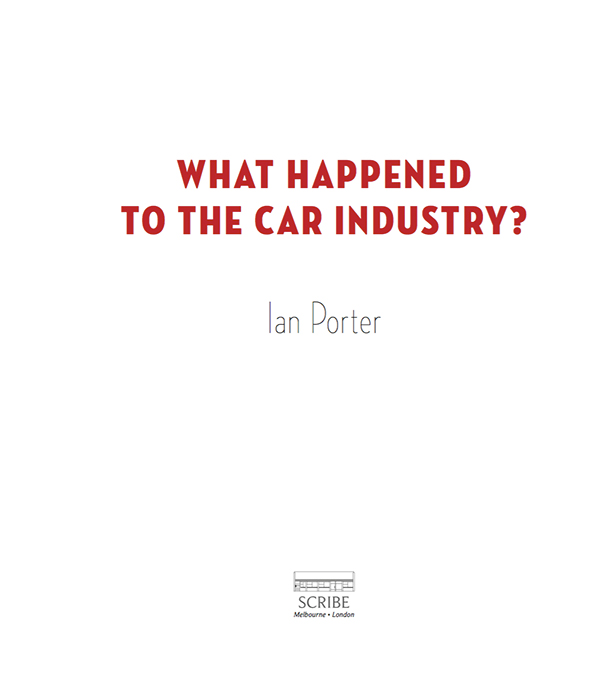

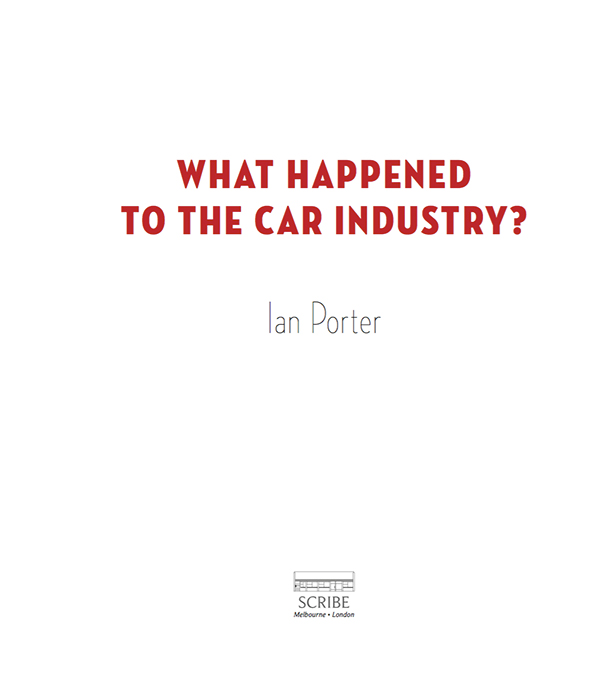

WHAT HAPPENED TO THE CAR INDUSTRY?

The first story Ian Porter wrote when he joined The Age in 1971 was about the car industry. The automotive sector has been the main theme in his journalism career, whether he was at The Age , The Advertiser , or the Australian Financial Review . He has reported from Europe, Japan, Korea, and China, and has also worked as a business editor, columnist, commentator, and motor-racing reporter. He lives in Melbourne with his wife, two children, a 2005 Mitsubishi 380 made in Adelaide, and a 1964 Morris Cooper S made in Sydney.

To the auto workers of Australia

Scribe Publications

1820 Edward St, Brunswick, Victoria 3056, Australia

2 John Street, London, WC1N 2ES, United Kingdom

Published by Scribe 2016

Text copyright Ian Porter 2016

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publishers of this book.

9781925321500 (pbk)

9781925307917 (ebook)

A CiP record for this title is available from the National Library of Australia

scribepublications.com.au

scribepublications.co.uk

Contents

by Kim Carr

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

by John Spooner

Foreword

By Senator Kim Carr

The announced shutdown of car manufacturing in Australia by the end of 2017 was not inevitable. It was the result of a political decision by the Abbott government to withdraw support for the industry. That decision was an act of economic vandalism, with costs that will far exceed the value of the co-investment that the Commonwealth makes in the industry through the Automotive Transformation Scheme.

The shutdown threatens the jobs of at least 160,000 people, and possibly up to 200,000, and analysts predict it will rip a $29 billion annual hole in the economy. If new investment is not found, Australias advanced manufacturing capabilities of which the automotive industry has always been the great repository will be endangered. These consequences should always have been apparent to the Coalition, but it was not deterred by them.

Before the Coalition took office in September 2013, I served as industry minister for much of the former Labor governments term. Together with industry department officers, I conducted negotiations with General Motors Holden for the production of two new models, and cabinet approved plans for renewed co-investment. I have no doubt that if the election result had been different, there would be no shutdown. Holden also kept the LNP opposition advised of its plans for $1 billion in new investment, and expressed its desire to stay in Australia.

But the election intervened, and the Coalition was hostile to the car industry from the outset. I was in contact with the General Motors board at the time, and commented publicly that the government was playing chicken with the international automotive companies. Tony Abbott and his senior ministers always made their intentions clear: they would goad the carmakers into leaving the country.

Early in December 2013, even before the Productivity Commission had released a report on the industry commissioned by the government, Mr Abbott said, Theres not going to be any extra money over and above the generous support the taxpayers have been giving the motor industry for a long time. A few days later, the then deputy prime minister, Warren Truss, and the treasurer, Joe Hockey, used question time in parliament to launch a blistering attack on Holden.

For months, Holden had been in commercial-in-confidence discussions with the government about an increase in assistance to offset the competitive disadvantage caused by the very high Australian dollar. But Mr Hockey said it was time for the company to come clean and to be fair dinkum with the Australian people. Either youre here or youre not, the treasurer said. Mr Truss, who was acting prime minister at the time, said: today I have written to the general manager of Holden, Mr Devereux, asking General Motors to make an immediate statement clarifying their intentions in this country.

The real message, as Ian Porter shows in this book, was not the stated request for clarification. It was an implied threat, and General Motors management in Australia and Detroit immediately understood it as such. The Age reported a text message sent by a company strategist: Are you seeing this question time attack on Holden? Taunting [us] to leave. Its extraordinary.

The government got its wish. As soon as he heard the remarks, the managing director of General Motors Holden, Mike Devereux, reported them to Detroit, and he was instructed to announce the shutdown. That, in turn, set in motion the events leading to the present crisis.

Soon after Holden made its announcement, Toyota followed suit, arguing that without at least two carmakers in the country there would be insufficient demand to sustain the component makers in the supply chain, who provide much of the industrys skills base and many of its jobs. Ford, the third carmaker, had already made its own decision to leave, so a day of verbal bludgeoning in parliament had brought the curtain down on 90 years of motor-vehicle production in Australia.

It is an astonishing tale of political malice driven by ideology, with cataclysmic results. Porter interweaves this narrative with the broader history of the car industry in this country, and in doing so lays bare the ignorance Abbotts ministers displayed in that dismal December.

Ultimately what it comes down to, Joe Hockey said, is [that] prosperity only comes from hard work and enterprise; it doesnt come from the benevolence of taxpayers. This is a statement as uninformed as it is arrogant. The history of automotive manufacturing in Australia is a history of hard work and enterprise, which has generated far more in economic activity and returns from the industry than the relatively modest amounts spent on it by the taxpayer.

The global esteem for the technological expertise and design skills of Australias automotive industry is reflected in the fact that both Holden and Ford will retain design centres and proving grounds in Australia after they cease manufacturing. The reality is that there is no country with an automotive industry that does not support it in some way, because all governments apart from the Australian Coalition government that took office in 2013 have recognised the crucial role that the industry plays in advanced manufacturing.

If we want an Australian economy that is not excessively dependent on the vagaries of commodity markets, we do not have a choice about whether to have a manufacturing sector, and we must do everything possible to retain the industrial capabilities that the automotive industry sustains.

I am confident this will happen. There will be an automotive industry after 2017, and it will involve manufacturing in some form, though the focus may not be on the production of passenger cars. And there is more than a glimmer of hope that even automobile production will continue.

Porter closes his story with a survey of new investment proposals. One of them, a bid by the Belgian-based firm Punch International to acquire Holdens plant in South Australia and continue making the Commodore, received favourable attention from the Turnbull government, but negotiations between Punch and General Motors were not successful. Punch, however, has stated that it is still interested in pursuing opportunities in automotive manufacturing in Australia.

Next page