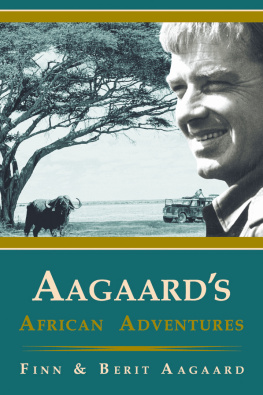

In a book of this length, covering such enormous areas of yet-untamed Africa, it would be impossible to thank all those people who were of such help and value to me. That is why an attempt was made throughout the text to mention those people as they appeared.

I should like, however, to express my deep gratitude to all the members of Hunters Africa, who have been so incredibly efficient and courteous. I have made new friends in that organization. And I owe Gordon Cundill a special word of appreciation for his Foreword to this book; for his support, advice, and genial company; and for his solid friendship, which has meant a great deal to me.

Gordons office staff in Pietermaritzburg will always be remembered, since they put the show together, from airline bookings to gun permits to a host of other details the outsider never sees. Thank you, Nora Chapman, Pam Mais-trey, Angie Leaker, and Lynn Palmary.

Lew and Dale Games were stars, backed by their colleagues in Lusaka. And I remember here my old pals of so long ago, Joe Joubert and Daryll Dandridge, as well as newfound friends in Steve Liversedge, the Riggs brothers, and Andre de Kock.

The visit to Linyanti will always be rather special in my memories of these safaris. I remember John Northcote and, in particular, Daphne and Mike Hissey. I am sorry indeed Mike is no longer with us so that he could read these words. He will not be forgotten.

My friend of longest standing in Africa, Stuart Campbell, was a huge treat to see again, and I should like to thank him and Eric Wagner for their hospitality at Matetsi, where I literally dug into my past, enjoying grand bird shooting and the finest treatment.

Paul Kimble and Dick van Niekerk, my photographers on different segments of the safaris, were both reliable and skilled, taking their chances while they captured many special moments on film for the book. I only regret Dicks run-in with a dangerous spider, as it removed a great deal of the enjoyment of the jaunt for him.

To those of you who flew us, met us, smoothed out problems at Customs and elsewhere, transported us, and saw to our every need, know that you are remembered with gratitude, as are all my African bush friends whose bravery I shall never forget.

My files were invaluable in writing this book and it is here that I should like to thank Jessica Coughlan for her meticulous clipping service and ongoing interest in my work.

Finally, my wife, Fiona Claire Capstick, who not only typed the entire manuscript, but also used her literary talents in making suggestions along the way. She was there.

This book would have hardly been possible to produce without the valued cooperation of Contax-Yashica, courtesy of my good pal, Steven Erasmus, who provided a Dukes ransom in camera bodies, Zeiss lenses, tripods, and the rest of the paraphernalia for which all the above firms are so revered and, also, but not secondarily, the huge cooperation of Cecil Horowitz of Photo Agencies, distributors of Fuji Film in southern Africa. Gentlemen, I thank you and your firms much more than I can say. Madoda, tina bonga wenazonke kakulu.

While this is hardly a commercial book written on behalf of Gordon Cundill and his hearty band of archers, it seems less than fair not to let you know where to reach him should you wish to experience an African safari in expert hands. Cundill does not advertise; he doesnot have to. However, you can reach him at:

Gordon J. P. Cundill, Esq.

P.O. Box 2078

Pietermaritzburg, 3200

Republic of South Africa

Telex: SA 643335

Telephone: (International Code) + 0331-34317

I did not choose Gordon Cundill and his cohorts by accident. They have been directly responsible for a most significant year in my life, and I hope that as you read, you have savored some of the pleasures I experienced.

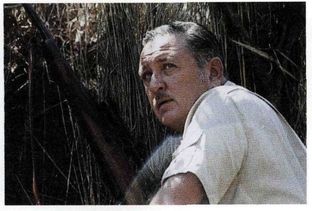

Peter Hathaway Capstick

Saile

T hrough the back of the head, whispered Gordon Cundill in the tiniest of tones.

Keeping my eyes locked on the hazy outline of the huge lion, I eased the .375 H&H Magnum to my shoulder. Even through the low setting of the variable scope, his head looked like a small townhouse with excess shrubbery, just a peripheral halo of mane and mass, facing nearly away from me. With an imperceptable snick, I flipped the magnetic scope post into position, held as best I could through the heat waves reflected by the searing Botswana sun that would have staggered a Venetian glass-blower, and leveled at the spot where I reckoned his head met his neck. High, I would take the base of the skull; low, and the spine wouldbe shattered. Either way, a record-book lion for the wall.

If I pulled the shot aside on a horizontal angle, however, both Gordon and I knew what would happen.

It did.

After five and a half days of tracking and two close encounters of the worst kind, I could only see a long, grass-shielded impression of the Tau entunanyana as he is so pronounced in Tswanajust his head; one ear and the curve of his skull. I knew he was accompanied by a female, with whom he had been doing what came naturally but at a rate and frequency that would astonish any human. (Hows about a roll in the hay every twenty minutes? Maybe you, brother, are up to such acrobatics but I have had back problems recently.) I lined up the sights, knowing the 300-grain Winchester Silvertip would have to bull through considerable bush and grass, and aware that a deflection was not only possible but probable. I eased off the trigger of the custom Mauser anyway.

That was a major and very nearly fatal error.

Whether through bush deflection, lousy shooting (for which I am not especially known), or simple bad luck, the tremendous lion jumped fifteen feet into the air, swapped ends, and came down in what was most certainly our direction. I believe that he charged the sound of the shot, rather than Gordon, Karonda the gun bearer, and me, as our cover was as good as his. With more than five hundred pounds of male lion coming at us as quickly as he could manage, however, the matter was academic and fast becoming immediate. Unfortunately, he had to clear some heavy cover, mostly mopane scrub, before we could take a second whack at him and have, even in African terms, a relatively clear shot.

He broke around a clump of mopane some ten yards from where he had been lying with his paramour, in company with two fully grown but nontrophy-sized lions. When I tell you that he charged, I use the term not lightly. He wanted us. Badly. Later, we were to discover one of several good reasons was that he contained a not inconsiderable amount of buckshot in his guts, about the American equivalent of a Double-0. They were old wounds but had still made a clear impression on his future attitude toward humans.

As he rounded the clump of bush, you can absolutely bet that I had one thing on my mind: putting as many 300-grain bullets into that bastard as soon as possible and before our acquaintance became any more intimate. I had been knocked down by lions seriously intent on biting me on a couple of previous occasions and was not especially eager to repeat the scenario.