T he author would like to express his usual deep thanks and appreciation to his wife, Fiona Claire Capstick, for her help during the Bushmanland trip and her tireless editing and suggestions as to the manuscript.

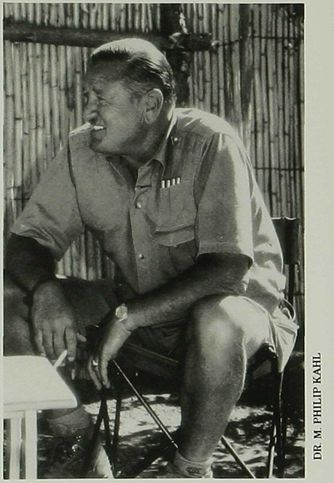

Thanks of the warmest kind are due to Dr. Philip Kahl for his patience and fine work in capturing on film some of the days we will see no more.

Dr. Anthony Hall-Martin, Director of Special Services of the South African National Parks Board and a prominent author and conservationist, deserves special thanks for his time and for his wisdom. Thanks, old friend.

Volker and Anke Grellmann, thanks for all your trouble, expense and expertise. It wouldnt have been an elephant book and video without you. We all appreciate your hospitality so much!

Thanks of the highest order are also owed to Roger Olkowski, who kept trying with that Betacam until it was right. Also, the greatest appreciation to Doug and Angi Stephensen, who, between them, kept both our bellies and our horizons full!

I would also like to thank sincerely the staff at Anvo Safaris, Johnny, Jonas, Mateus and the rest of the men and women who made our stay in Bushmanlan so wonderful.

Special thanks to Jerry and Bam Heiner, who were always charming and entertaining, as well as generous in letting us film their hunt. Thanks especially to Bam, who remembered that I love Triscuits and brought a supply some twelve thousand miles!

Ken Wilson, producer and editor of CapstickHunting the African Elephant , gets special mention for his patience and skill.

It would not have made a book or video without the manyJu/Wasi Bushmen who helped us and who were so loyal. I wish you better times, my friends.

The most appreciative thanks also go to Arnold Huber, who worked constantly for us to get the Bushmen exposure that we wanted. His work is very much appreciated by all of us.

I would like especially to thank my agent, Richard Curtis of New York City, for his patience and hard work in getting this project off the ground. The same appreciation goes to my editor, Michael Sagalyn of St. Martins Press, Inc., also of New York, as well as his assistant, Ed Stackler, who took so much of the heavy labor of this book in his stride.

Thank you, all of you.

Death in the Long Grass

Death in the Silent Places

Death in the Dark Continent

Safari: The Last Adventure

Peter Capsticks Africa: A Return to the Long Grass

The Last Ivory Hunter: The Saga of Wally Johnson

Maneaters

Last Horizons: Hunting, Fishing, and Shooting on Five Continents

Death in a Lonely Land: More Hunting, Fishing, and Shooting on Five Continents

From the successor to Ruark and Hemingway comes the most lavishly illustrated, historically important safari ever captured in print.

Peter Hathaway Capstick journeyed on safari through Namibia in the African spring of 1989. This was a nation on the eve of independence, a land scorched by the sun, by years of bitter war. In these perilous circumstances, Peter Capstick commenced what is surely the most thrilling safari of his storied career. He takes the reader to the stark landscape that makes up the Bushmens tribal territories. There, facing all kinds of risks, members of the chase pursue their quarry in a land of legend and myth. The result is an exciting big-game adventure whose underlying themes relate directly to the international headlines of today.

In this first-person adventure, Capstick spins riveting tales from his travels and reports on the Bushmens culture, their political persecution, and the Stone Age life of Africas original hunter-gatherers. In addition, the author explains the economic benefits of the sportsmens presence, and how ethical hunting is a tool for game protection and management on the continent.

Not since Peter Capsticks Africa has the author taken the reader along on safari. In this superbly illustrated book, Capstick returns to the veld with an ace video cameraman and leading African wildlife photographer Dr. M. Philip Kahl. One hundred of Dr. Kahls striking color photos capture perfectly life and death in "the land of thirst."

PETER HATHAWAY CAPSTICKS nine prior titles include Death in a Lonely Land, The Last Ivory Hunter, Peter Capsticks Africa, and Death in the Long Grass. After leaving Wall Street, the New Jersey native hunted in Central and South America before going to Africa, where he held professional hunting licenses in Ethiopia, Zambia, Botswana, and Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). The author has long made his home in Africa, the source of his inspiration.

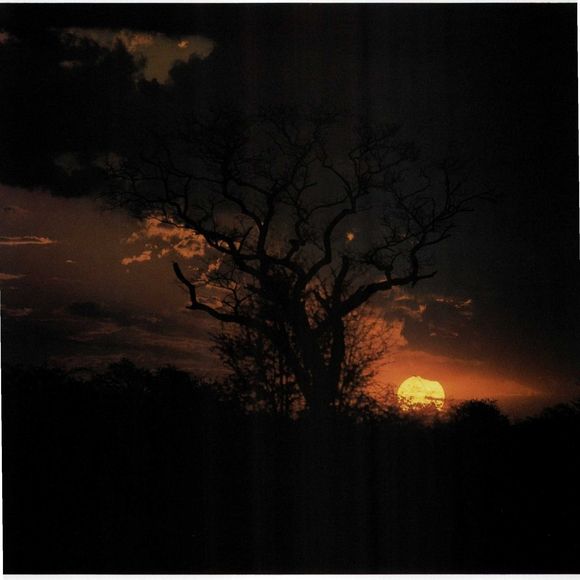

T he dead dog hung transfixed by a moonbeam. Below it, the knuckles of an elephant loomed in the same yellow light as a full moon eased to its zenith, bathing the scene in golden rays almost as bright as daylight. I tapped Volker lightly for the owl-eye, and pointed it over the top of the black .375 Magnum rifle. It rasped slightly against the dry salt on my cheeks as I focused the device and looked through the lenses. Edged in green, the light it drew was astonishing, each blade of the Kalahari-withered grass as sharp as a sword and each jagged stick of bush plated with the same winter-weary edging. In a silent click, I turned off the battery element and quietly handed it back to Volker. He took it with exaggerated slowness and carefully placed it on his lap without turning his head in the least.

Far, far away, I could hear a bushbaby crying on the hot, dry night air, and once there was the closer yap of a black-backed jackal, slicing the cooler wind like a serrated bread knife. From almost a mile away came a quiet cough from the Bushman encampment at Naneh, where perhaps fifty souls lay sleeping by the fires in a swelter of sweat and heat. Certainly they were no hotter than we were, I thought as I eased my bum slightly on the canvas seat of a camp chair inside the blind and collected a black glance from Volker. Above, a satellite drifted as silently as the stars across the gem-filled sky, coming from our left and dying out of sight to our right. I wondered whose it was. Could it really see a golf ball at two hundred miles? Who would want to see a golf ball so far away, anyway? My brain scrambled and I furtively fished out my watch from the little pocket I had always questioned the use of. Ten past one. Good. Another fifty minutes before it was my turn to stare at that fool tree thatmight sprout a monster dog-and-cow-killing leopard. I closed my eyes after a glance at Volker, who was hunkered like a huge heap on the edge of his chair, and was figuring out how to spend all that money from the Pulitzer Prize when I felt it .

It spoke for itself, a thick, strong grip that actually hurt my upper arm. I knew better than to react, just sliding my eyes open an almond sliver and staring straight ahead. I started to shift forward, but the grip increased along with several damned painful tightenings from the huge hand that had grabbed me. Slowly I went over our signals. One nudge or grip meant that the watcher had seen the leopard on the ground, but there was no change in the sere, sandy northern Kalahari that separated us from the tree. Two squeezes or pulses mean that the leopard was in the tree. No, again. But what in hell did a very solid and sustained grip mean? Oh, my! Maybe snake?